Changes in Health-Related Quality of Life During Multiple Myeloma Treatment: A Qualitative Interview Study

Purpose: To explore whether patients with multiple myeloma changed their construct of health-related quality of life during treatment.

Participants & Setting: 14 participants were selected from 10 hematology-oncology departments in Denmark.

Methodologic Approach: This interview study used a prospective, longitudinal, exploratory design. Semistructured interviews were conducted while participants were undergoing active treatment for multiple myeloma and six months after the baseline interview. Interviews were analyzed using systematic text condensation.

Findings: The overall theme at baseline was insecurity, and the overall theme at six months was coping. The following subthemes were also identified based on participants’ description of their health-related quality of life: concerns about having a meaningful life, dealing with everyday limitations, and maintaining social networks; adjusting expectations to abilities; expanding social networks; and exploring a meaningful life.

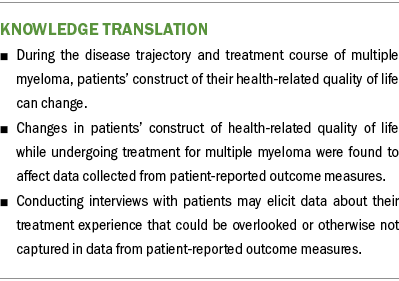

Implications for Nursing: Patients’ ability to use coping strategies should be considered when screening for rehabilitation needs. During systematic in-depth symptom screening, unmet rehabilitation needs (e.g., physical functioning, fatigue, pain) may become apparent.

Jump to a section

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematologic cancer, with an incidence of 7 in 100,000 people per year (Padala et al., 2021). However, the use of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation and novel therapeutics has improved survival (Rajkumar, 2020). Clinical presentation of MM can include bone lesions, renal insufficiency, anemia, hypercalcemia, and immunodeficiency, which can lead to infection (Kyle et al., 2003). Most patients with MM present with a high symptom burden and report lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) compared to patients with other hematologic cancers (Baz et al., 2015; Boland et al., 2013; Johnsen et al., 2009; Jordan et al., 2014). HRQOL is defined as a multidimensional construct that encompasses perceptions of the positive and negative aspects of dimensions produced by disease or its treatment (Osoba, 1994).

Results from HRQOL measures are increasingly being used in healthcare decision-making, including in oncology drug development, patient care, organizational policies, and healthcare politics (Kluetz et al., 2018). Changes in HRQOL in patients with MM have mostly been investigated using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire–Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and EORTC QLQ–Multiple Myeloma Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-MY20) (Aaronson et al., 1993; Cocks et al., 2007; Nielsen et al., 2017). One concern with using longitudinal PROMs is that patients may understand items and response categories differently as they go through new life experiences, making comparisons between scores difficult (Edwards et al., 2018; Sommer et al., 2020). Measurement invariance is an important component of a PROM instrument and refers to a stable relationship between the item and the latent construct being measured (Meade & Lautenschlager, 2004). The EORTC QLQ-C30 has been investigated for measurement invariance, and studies have found that it provides valid results in between-group comparisons with only a few exceptions (Costa et al., 2015; Sommer et al., 2020; van Roij et al., 2022). Measurement invariance evaluation was not included in the development and validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-MY20 in patients with MM (Cocks et al., 2007; Stead et al., 1999; Wisløff et al., 1996).

In a systematic review of longitudinal studies using the EORTC QLQ-C30 to investigate changes in HRQOL in patients with MM, Nielsen et al. (2017) found that improvements in HRQOL were reported only in patients newly diagnosed with MM. Studies have reported that patients with cancer, including those with MM, can experience positive changes in HRQOL that surpass changes in control group scores, particularly when facing life-threatening disease (Cella & Tross, 1986; de Camargos et al., 2020). This phenomenon, known as response shift, involves changes in internal standards, values, or QOL conceptualizations and has been recognized in several studies (Danoff et al., 1983; Schwartz & Sprangers, 1999; van Rijn, 2009). The effects of response shift have been investigated in patients with MM across four domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (Kvam et al., 2010). Kvam et al. (2010) found that patients with MM who experienced deterioration during a three-month observation period changed their internal standards compared to baseline and experienced response shift.

Appraisal is one method to understand individual differences and changes in internal standards, values, and conceptualizations related to QOL (Rapkin & Schwartz, 2004). The QOL Appraisal Profile (QOLAP) consists of the following four key parameters (Rapkin et al., 2017):

- Frame of reference: the meanings the individual attaches to questions

- Sampling of experience: specific experiences within their frame of reference

- Standards of comparison: comparing previous experiences within the frame of reference

- Combinatory algorithm: a combination process that individuals use to consider different experiences and arrive at an overall evaluation

QOL appraisal has been proposed to shed light on response shift when measured repeatedly over time. The impact that response shift has on changes in longitudinal HRQOL scores can be hard to understand because the internal processes are not completely understood. This makes it beneficial to examine response shift when trying to interpret patients’ longitudinal HRQOL scores (Rapkin & Schwartz, 2004).

Qualitative methodologies, such as semistructured interviews, offer an informative approach to investigate the impact of disease on patients’ lives (Malterud, 2001). These methods can also explore the cognitive and psychological mechanisms underlying the question-answering process (McHorney & Fleishman, 2006). Although studies have been conducted using interviews to explore HRQOL in patients with MM, there is a lack of qualitative studies using a longitudinal design that can capture fluctuations in HRQOL (Hauksdóttir et al., 2017). Therefore, the aim of this interview study was to explore whether patients with MM change their construct of HRQOL while undergoing treatment to six months thereafter.

Methods

Design, Sample, and Setting

The current study is a secondary analysis of a study by Nielsen et al. (2020) of QOL in Danish patients with MM (the QOL-MM study). This study was inspired by hermeneutics philosophy and designed as a prospective, longitudinal, qualitative study using a semistructured interview with a six-month follow-up interview. The QOL-MM study (Nielsen et al., 2020) is an ongoing longitudinal survey, in which patients newly diagnosed with MM and patients with relapsed MM are evaluated at the time of treatment.

From September to November 2018, patients from 10 hematology-oncology departments in Denmark were invited to participate in the interviews. Patients were included if they were undergoing treatment for newly diagnosed or relapsed MM, participating in the QOL-MM study, able to understand Danish, able to provide informed consent, and without a mental disorder that would have prevented them from independently answering the interview questions. Patients who did not understand the Danish language or were diagnosed with a psychiatric condition were not eligible.

Data Collection

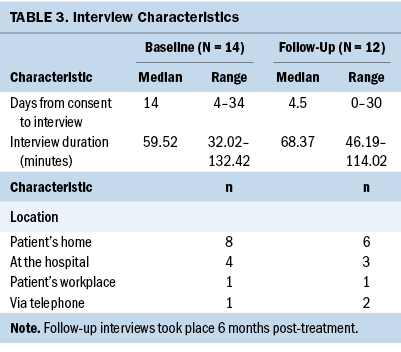

Participants who provided informed consent for the current study were contacted by a research team member to promptly schedule the baseline interview. The location of the interview was based on the participant’s preference, with privacy and individual settings preferred for discussing sensitive HRQOL issues (Edwards & Holland, 2013). Interviewers and participants were not acquainted beforehand, and participants were assured that participation in the interview would not affect their treatment. The second interview took place six months after the initial interview, with considerations given to participants’ symptom relief and avoidance of relapse for data interpretation. For patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation, the six-month interview was conducted no earlier than two months after transplantation to account for symptom recovery (Chakraborty et al., 2018). Both first authors (L.S. and J.R.D.) conducted the interviews to ensure consistency, and the same interviewer handled the transcription. Interviewers had limited prior knowledge of the participants, with only demographic data being made available from the QOL-MM study.

Measures

The interview guide consisted of two parts. In the first part, the researchers used a semistructured exploratory interview with open-ended questions to encourage participants to speak freely about their illness, experiences, and needs. The second part of the interview followed a more structured design. A short briefing took place before conducting the interviews to explain the purpose of the interview and address any questions from participants. The researchers ensured that the interviews were relevant for the study aim but also allowed participants to elaborate on perspectives and thoughts, even if they were not covered by the interview guide (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2014). Throughout the interviews, the interviewers were flexible regarding the order of questions if topics were mentioned out of order.

The first part of the interview consisted of items that were designed to allow participants to elaborate on HRQOL in their own words. This included items such as “What does the word ‘health’ mean to you?” and “What does quality of life mean to you?” In the second part of the interview, the researchers explored the four elements of the QOLAP by developing interview questions from PROM questionnaires used to evaluate HRQOL in the parent study, including the EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-MY20, and EORTC QLQ–Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy modules. The following 12 HRQOL domains were examined: physical functioning (e.g., “Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities?”); role functioning (e.g., “Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities?”); emotional functioning (e.g., “Do you feel depressed?”); cognitive functioning (e.g., “Have you had difficulty remembering things?”); social functioning (e.g., “Has your physical condition or treatment interfered with your social activities?”); fatigue (e.g., “Have you felt weak?”); pain (e.g., “Have you had pain?”); disease symptoms (e.g., “Did pain interfere with your daily activities?”); global QOL (e.g., “How would you rate your overall health during the past week?”); peripheral neuropathy (e.g., “Did you have numbness in your fingers or hands?”); physical health (e.g., “During the past four weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of your physical health?”); and mental health (e.g., “During the past four weeks, have you had any of the following problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of any emotional problems?”) (Aaronson et al., 1993; Cocks et al., 2007; Postma et al., 2005; Ware et al., 1996).

Because the domains of pain and disease symptoms are evaluated using similar items, these two domains were combined under the same questions in the interview guide. Closed-ended PROM items were converted to open-ended questions in the interview guide, and four questions were asked for each domain. For example, the following questions were used to elicit data about participants’ experiences with pain:

- “How do you assess whether you feel pain?”

- “What is your previous experience with pain?”

- “Who do you compare yourself to when you assess whether you feel pain?”

- “Are there other conditions that apply when you assess whether you feel pain?”

The interview guide was thoroughly reviewed by all researchers to ensure that understanding of questions and final study aims were clear. Following the interview, a short debriefing took place where participants could add comments or ask additional questions. The same interview guide was applied for the baseline interview and the six-month follow-up interview.

Data Analysis

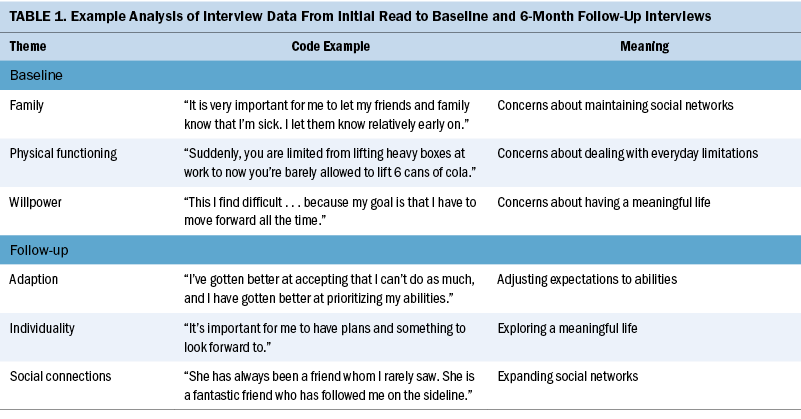

Interview data were analyzed using systematic text condensation (Malterud, 2003). This method allows for a descriptive analysis of participants’ perspectives without exploring underlying meanings. The analysis consisted of four steps. First, an overview of the data was created by reading all transcripts, with each researcher listing their preliminary themes and negotiating confluent and diverging issues. Three themes were chosen for further analysis. Second, meaning units were identified, which were text fragments that contributed to answering the study aim. Then, each meaning unit was coded related to the previously negotiated themes. Third, all meaning units were sorted into one of the three coding groups found during the second step. The meaning units were sorted into subgroups, each subgroup was analyzed, and a condensate was created. Fourth, data were reconceptualized, creating meaningful descriptions of participants’ experiences. Each code group was given a headline expressing the final theme. The themes that emerged from the baseline and six-month interviews are illustrated in Table 1.

Through this process, one overarching baseline theme and one overarching six-month theme, each with three subthemes, were identified. Comparing the fragments and meaning units from these two time points allowed for the identification of any changes in participants’ perceptions of HRQOL. Both first authors (L.S. and J.R.D.) examined and discussed the interviews to ensure consistency, and the findings were discussed with all researchers to ensure objectivity and validate the findings.

Ethical Considerations

In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013), participants received oral and written information about the study and were included only after providing informed consent. According to the Danish Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects, approval is not required for interview studies. The study was registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency, and interview data were stored securely on a Microsoft SharePoint site.

Findings

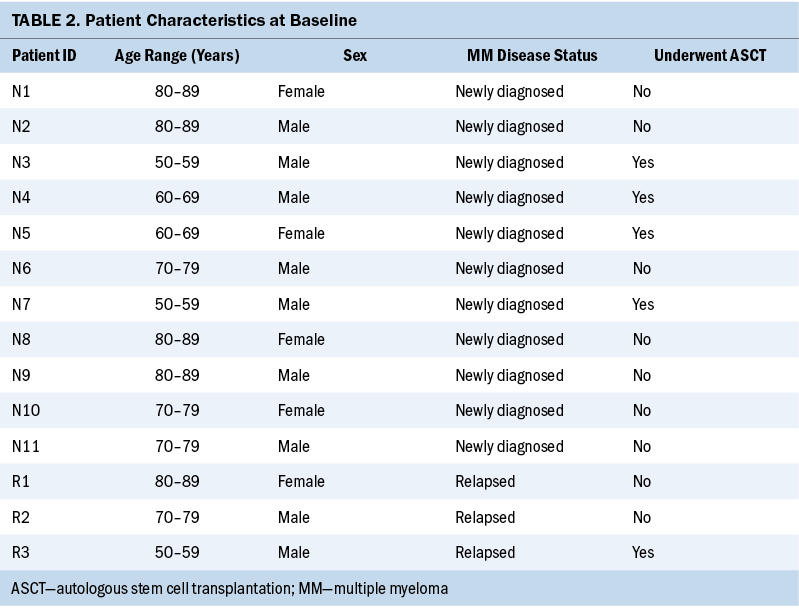

Of 43 eligible participants, 14 were included. The median age of participants was 73 years (interquartile range = 65–80). Eleven participants were newly diagnosed with MM, and three participants had relapsed MM. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2. Overall, 14 participants completed the baseline interview, and 12 participants completed the six-month interview. In addition, one participant died and one participant withdrew consent prior to the six-month interview. Interview characteristics are presented in Table 3.

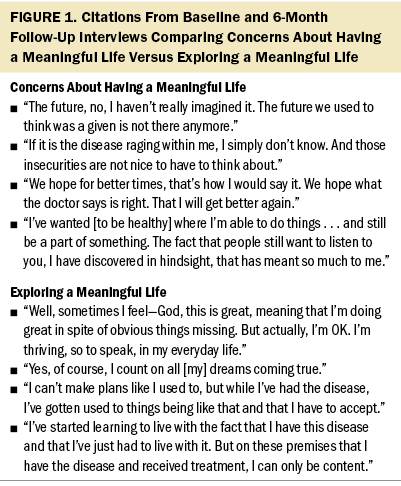

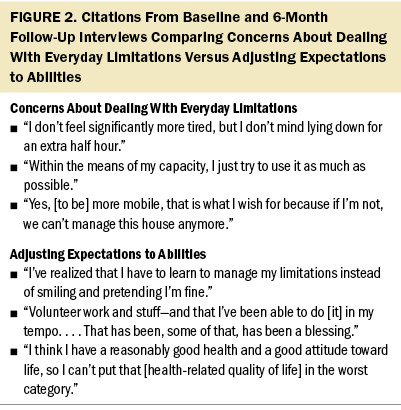

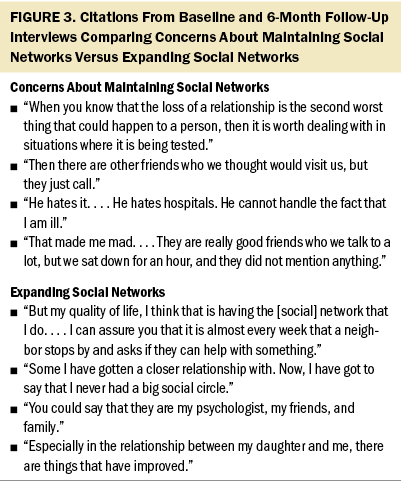

The overall theme at baseline was insecurity, and the overall theme at six months was coping. Subthemes for insecurity were concerns about having a meaningful life, dealing with everyday limitations, and maintaining social networks. The subthemes for coping were adjusting expectations to abilities, expanding social networks, and exploring a meaningful life. The following sections elaborate on the overall themes and subthemes, citing participants’ responses. Figures 1–3 present additional reports from participants, illustrating changes in their HRQOL.

Insecurity

During the baseline interview, participants expressed feeling distressed about the uncertainty of the disease trajectory and treatment effectiveness, leading to concerns about future changes in their lives, such as job security and housing stability. The unpredictable nature of MM, with alternating periods of remission and relapse, made it challenging for participants to anticipate the course of their lives. In addition, maintaining close social support was a concern for participants because they hesitated to openly discuss their uncertainties about the disease trajectory.

Concerns about having a meaningful life: Participants emphasized the significance of health in their overall HRQOL, considering it a vital aspect for mental and physical well-being. Participants wanted to continue experiencing passion, fulfillment, and a purpose in life: “I would like to experience the last years of my life, where I can control my own life, where I have time to enjoy things, time to do things” (participant N4).

Participants also emphasized the need for freedom and the importance of living a life unrestricted by physical symptoms: “The worst health must be somebody who . . . just sits down and doesn’t do anything other than, well, they have lost their passion and, of course, they are very sick, right?” (participant N9).

Concerns about dealing with everyday limitations: Participants were experiencing physical limitations because of symptoms related to MM, particularly symptoms affecting the bones. As a result, they were advised to avoid activities such as carrying heavy shopping bags and were dependent on help from friends and relatives: “You are bound in this way that you are dependent that someone is coming. You can’t do this and this. You are limited” (participant R1). These limitations were perceived as frustrating and limited participants’ senses of individuality because they had previously been able to perform housework and daily chores independently: “I have been challenged. It irritates me that I have to ask for his or my children’s help, where I think . . . you should be able to handle this yourself” (participant N4).

Concerns about maintaining social networks: Participants hesitated to engage in intimate conversations about their disease with friends and relatives. They also found it challenging to speak openly about uncertainties because they feared being met with discomfort:

I have tried a few times with some friends we know . . . who didn’t say anything when we met. And it really annoyed me. . . . It’s the worst thing people can do. It’s not because they need to talk a whole lot about it. But just ask and acknowledge, “I know that you are sick, and so what.” (participant N3)

Participants struggled to rely on their partners for support because their partners were also grappling with uncertainties about the future and the fear of potential loss: “He must see me alive in some way, so I have spared him a lot . . . but it wears him out. . . . He must figure our relationship out because we have been married for 51 years. ‘Do I lose her?’” (participant N1).

Coping

During the follow-up interview, patients began seeking coping strategies to manage their MM diagnosis and accompanying symptoms while maintaining daily activities. This new approach instilled hope in them, enabling them to continue leading a meaningful life despite their diagnosis. By adapting to limitations and actively participating in everyday life, participants felt that they were making a positive impact within their community again. Participants emphasized the growing significance of social support, with many finding solace within their close social circle or through online groups. As a result, participants experienced a renewed sense of hope for the future and discovered innovative ways to navigate their altered circumstances.

Adjusting expectations to abilities: Compared to baseline, participants experienced worse levels of symptoms six months after treatment, particularly fatigue and pain. Regardless, they described navigating everyday life and finding ways to maintain activities of daily living. Therefore, they did not report any limitations when completing the HRQOL measures:

I try to readjust it in a way, so my work function will suffice, so when I have worked three hours, then I need to do something else. Then, I need to rest my leg for an hour because it will swell and get very tight. (participant R2)

Participants adjusted their daily activities based on their physical capabilities and started accepting that they had to do things differently compared to how they would do them prior to diagnosis. This meant that participants were still positive about their ability to cope with their physical difficulties and did not find their limitations important enough to report when asked: “When I go shopping, for example, in a mall . . . then I know I need to go there, and then to the other end. There will be benches all the time. . . . I’ll sit and pretend I’m doing something” (participant N8).

Expanding social networks: Seeking out social support online and in person made it easier for participants to speak openly with friends and connect with acquaintances who were also dealing with malignant disease: “I had never thought that I would share it on Facebook, but it was a way to keep people updated. . . . It has actually felt really good. . . . It has become easier to talk about it” (participant N3).

Participants reported that they had old friends reaching out, and connections were reestablished. Being more open about their disease meant that participants were also able to communicate with loved ones and share the difficulties they were facing more openly: “I was thinking afterwards that I barely spoke with my own children about it. . . . I expect that we will talk more about it . . . so we can [process it]” (participant N2).

Exploring a meaningful life: It was important for participants to still lead an independent life and have the same values as they did prior to their diagnosis. They started comparing themselves to other patients with MM and still perceived their HRQOL as good, although their physical functioning had declined: “Well, I think considering that I have bone marrow cancer, then it’s fantastic. And if I have to compare, then I have to compare to others who also have it” (participant N3).

Patients were grateful that they were able to continue participating in household-related activities and hobbies. They felt they still had a meaningful life and things that they still wanted to accomplish: “I myself am astonished that I’m not [afraid]. I don’t know. I think I’m simply too busy living my life to the extent that I can” (participant R3).

Discussion

This is the first qualitative interview study of patients with MM that included a follow-up interview examining potential changes in constructs of HRQOL during a six-month treatment period. Semistructured interviews were selected based on the QOLAP to obtain a deeper understanding of the processes influencing patients’ HRQOL. Based on participants’ responses, two main themes of insecurity and coping were identified. Adapting to symptoms and reduced functioning can be perceived as a coping strategy resulting from recalibration. The reconsideration of values and priorities, reflected in participants’ reports of their increased need for social support and a meaningful life, suggests reprioritization. Stage of disease and future possibilities became more influential in participants’ perceptions of HRQOL, indicating reconceptualization (Sprangers & Schwartz, 1999). These findings suggest that participants may have experienced changes in their construct of HRQOL during treatment, which is consistent with previous findings (Kvam et al., 2010).

This study revealed that when participants were asked about their overall HRQOL, their responses did not reflect an increased symptom burden. However, when directly asked about specific symptoms and functional limitations, such as fatigue or pain, participants expressed worse symptoms and reduced function. This suggests that patients may not attribute significant importance to their symptoms when responding to a questionnaire, despite experiencing an increased symptom burden. In addition, participants began to compare themselves to other patients with MM, gaining new insights into their symptoms and limitations. This shift in perspective may have positively influenced their HRQOL scores. This finding also highlights the importance of adequate supportive care, which extends beyond disease control and patients’ physical well-being because perceptions of HRQOL contribute to patients’ perceptions of maintaining a meaningful life.

In this study, participants reported that their HRQOL was good during the follow-up interview, although they were experiencing side effects from MM and its treatment. This discrepancy between patients’ increased symptom burden and its effect on HRQOL could be explained by response shift. Vanier et al. (2021) proposed a revised model of response shift, reporting that response shift occurs when observed changes cannot be fully explained by changes in the intended outcome being measured. However, further investigation is necessary to establish evidence supporting a revised model of response shift based on discrepancies found with the QOLAP (Rapkin & Schwartz, 2019; Sawatzky, 2019; Sprangers et al., 2021). In addition, considering the definition of HRQOL, a clear distinction of whether the documented changes in HRQOL are a result of new experiences, a result of changes in the influence of physical health on HRQOL, or the development of HRQOL during treatment cannot be made based on the findings of the current study and warrants further investigation.

Hauksdóttir et al. (2017) found that patients with MM employed physical and emotional coping strategies. These coping strategies helped patients maintain a sense of equilibrium while navigating challenges from their diagnosis. The current study found that similar coping strategies were employed by participants during the six-month period. Participants developed new ways to manage their physical limitations and sought emotional support from their social networks. Coping strategies play an important role in helping patients deal with the negative physiologic effects of a chronic disease like MM.

During the six-month follow-up interview, participants expressed an increased need for social support, which they considered significant when assessing their HRQOL. This shift in focus from physical abilities to social support contributed to higher HRQOL scores (Molassiotis et al., 2011). The interviews also revealed unmet needs regarding seeking out new forms of social support, which may not have been captured through HRQOL measures alone.

Maintaining an active life was of great value to participants, and they found it challenging to refrain from engaging in hobbies and social gatherings the same way they had prior to diagnosis and treatment. During the six-month period, participants engaged in new activities or activities that had been a lower priority before their diagnosis (e.g., volunteer work, less physically demanding hobbies). This meant that participants still experienced a sense of meaning in their lives, which correlates to findings from Hauksdóttir et al. (2017), who found that when people are diagnosed with MM and other forms of cancer, it creates a sudden need to redefine previous priorities.

The implications of changes in HRQOL and their impacts on PROM scores should be considered when using HRQOL measures for healthcare decision-making. With the continued importance of establishing patients’ HRQOL, researchers have explored methods to examine the effects of new life experiences on PROM scores (Rapkin & Schwartz, 2019; Sawatzky, 2019; Sprangers et al., 2021; Taminiau-Bloem et al., 2010).

Limitations

The limitations of this study pertain to the qualitative data collected through interviews, the method for analyzing the data, and the low response rate (33%), all of which limit generalizability. The researchers’ preexisting understanding of the underlying factors affecting changes in HRQOL may have influenced the interpretation of the data. Of note, any description can be influenced by interpretation, and the aim of the study already guides the researchers’ perspectives (Malterud, 2003).

A larger sample size would have provided a broader range of patient characteristics and increased the transferability of findings. Participants had few comorbidities, and half were treated at the same hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark, which suggested a higher socioeconomic status. The burden of participation, involving HRQOL measures completed during a two-year period followed by interviews, may have deterred patients who were experiencing comorbidities or those with a higher symptom burden from participating.

Because participants received treatment at different hematology-oncology departments, the support they received from hospital staff varied. Although guidance provided by clinical staff regarding disease coping strategies and other psychoeducational initiatives is not typically considered in the interpretation of HRQOL scores, previous studies have shown a positive impact of such interventions on HRQOL in certain groups of patients with cancer (Setyowibowo et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, future intervention studies should explore the effect of psychoeducation on HRQOL, specifically in patients with MM.

Implications for Practice

The ability of patients to use coping strategies should be considered when screening for rehabilitation needs, as well as when providing person-centered care. Screening for unmet needs using data captured from PROMs can enable broader screening; however, important patient needs may be overlooked. During systematic in-depth symptom screening, unmet rehabilitation needs, such as physical functioning, fatigue, and pain, may become apparent. Despite these challenges, in-person screening still provides important information about patients and the obstacles they are facing because of their MM diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion

This study shows that there are changes in patients’ constructs of HRQOL during treatment for MM. The findings indicate that these changes can interfere with HRQOL based on the direct comparison of patients’ scores on PROMs over time. However, whether these changes are a result of new life experiences, a change in the construct of HRQOL as a concept, or a result of the development of HRQOL while undergoing treatment is not possible to determine based on the data collected and warrants further investigation. The findings also highlight that data from PROMs obtained from clinical trials and other longitudinal surveys of patients with MM should be interpreted with caution.

About the Authors

Lise Sonsby, MD, is a junior researcher in the Quality of Life Research Center in the Department of Hematology at Odense University Hospital and a first-year resident in the Department of Internal Medicine and Acute Medicine at Svendborg Hospital; Josephine Rahbæk Dueholm, MD, is a junior researcher in the Quality of Life Research Center and a first-year resident, both in the Department of Hematology at Odense University Hospital; Dorthe Boe Danbjørg, RN, PhD, is the vice president of the Danish Nurses’ Organization, an associate professor in the Faculty of Health Science at the University of Southern Denmark, and a research nurse at Odense University Hospital; Niels Abildgaard, MD, DMSc, is a clinical professor of hematology and the head of the clinical research unit in the Department of Hematology at Odense University Hospital; and Lene Kongsgaard Nielsen, MD, PhD, is a senior researcher in the Quality of Life Research Center in the Department of Hematology at Odense University Hospital and a staff physician and clinical associate professor in the Department of Hematology at Gødstrup Hospital, all in Denmark. Sonsby and Dueholm are dual first authors. No financial relationships to disclose. Sonsby and Dueholm completed the data collection. Dueholm provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Sonsby can be reached at lisesonsby@gmail.com, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted January 2023. Accepted May 24, 2023.)

References

Aaronson, N.K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N.J., . . . Takeda, F. (1993). The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

Baz, R., Lin, H.M., Hui, A.-M., Harvey, R.D., Colson, K., Gallop, K., . . . Richardson, P. (2015). Development of a conceptual model to illustrate the impact of multiple myeloma and its treatment on health-related quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(9), 2789–2797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2644-6

Boland, E., Eiser, C., Ezaydi, Y., Greenfield, D.M., Ahmedzai, S.H., & Snowden, J.A. (2013). Living with advanced but stable multiple myeloma: A study of the symptom burden and cumulative effects of disease and intensive (hematopoietic stem cell transplant-based) treatment on health-related quality of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 46(5), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.11.003

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2014). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage.

Cella, D.F., & Tross, S. (1986). Psychological adjustment to survival from Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(5), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.5.616

Chakraborty, R., Hamilton, B.K., Hashmi, S.K., Kumar, S.K., & Majhail, N.S. (2018). Health-related quality of life after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 24(8), 1546–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.03.027

Cocks, K., Cohen, D., Wisløff, F., Sezer, O., Lee, S., Hippe, E., . . . Brown, J. (2007). An international field study of the reliability and validity of a disease-specific questionnaire module (the QLQ-MY20) in assessing the quality of life of patients with multiple myeloma. European Journal of Cancer, 43(11), 1670–1678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.022

Costa, D.S.J., Aaronson, N.K., Fayers, P.M., Pallant, J.F., Velikova, G., & King, M.T. (2015). Testing the measurement invariance of the EORTC QLQ-C30 across primary cancer sites using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis. Quality of Life Research, 24(1), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0799-0

Danoff, B., Kramer, S., Irwin, P., & Gottlieb, A. (1983). Assessment of the quality of life in long-term survivors after definitive radiotherapy. American Journal of Clinical Oncology, 6(3), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000421-198306000-00015

de Camargos, M.G., Paiva, B.S.R., de Oliveira, M.A., de Souza Ferreira, P., de Almeida, V.T.N., de Andrade Cadamuro, S., . . . Paiva, C.E. (2020). An explorative analysis of the differences in levels of happiness between cancer patients, informal caregivers and the general population. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00594-1

Edwards, M.C., Houts, C.R., & Wirth, R.J. (2018). Measurement invariance, the lack thereof, and modeling change. Quality of Life Research, 27(7), 1735–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1673-7

Edwards, R., & Holland, J. (2013). What is qualitative interviewing? Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472545244

Hauksdóttir, B., Klinke, M.E., Gunnarsdóttir, S., & Björnsdóttir, K. (2017). Patients’ experiences with multiple myeloma: A meta-aggregation of qualitative studies. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44(2), E64–E81. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.ONF.E64-E81

Johnsen, A.T., Tholstrup, D., Petersen, M.A., Pedersen, L., & Groenvold, M. (2009). Health related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. European Journal of Haematology, 83(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01250.x

Jordan, K., Proskorovsky, I., Lewis, P., Ishak, J., Payne, K., Lordan, N., . . . Davies, F.E. (2014). Effect of general symptom level, specific adverse events, treatment patterns, and patient characteristics on health-related quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma: Results of a European, multicenter cohort study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(2), 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1991-4

Kluetz, P.G., O’Connor, D.J., & Soltys, K. (2018). Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. Lancet Oncology, 19(5), e267–e274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30097-4

Kvam, A.K., Wisløff, F., & Fayers, P.M. (2010). Minimal important differences and response shift in health-related quality of life; a longitudinal study in patients with multiple myeloma. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-79

Kyle, R.A., Gertz, M.A., Witzig, T.E., Lust, J.A., Lacy, M.Q., Dispenzieri, A., . . . Greipp, P.R. (2003). Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 78(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.4065/78.1.21

Malterud, K. (2001). Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet, 358(9280), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

Malterud, K. (2003). Qualitative methods in medical research (2nd ed.). Universitetsforlaget.

McHorney, C.A., & Fleishman, J.A. (2006). Assessing and understanding measurement equivalence in health outcome measures. Medical Care, 44(11, Suppl. 3), S205–S210. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000245451.67862.57

Meade, A.W., & Lautenschlager, G.J. (2004). A comparison of item response theory and confirmatory factor analytic methodologies for establishing measurement equivalence/invariance. Organizational Research Methods, 7(4), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104268027

Molassiotis, A., Wilson, B., Blair, S., Howe, T., & Cavet, J. (2011). Living with multiple myeloma: Experiences of patients and their informal caregivers. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0793-1

Nielsen, L.K., Jarden, M., Andersen, C.L., Frederiksen, H., & Abildgaard, N. (2017). A systematic review of health-related quality of life in longitudinal studies of myeloma patients. European Journal of Haematology, 99(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12882

Nielsen, L.K., King, M., Möller, S., Jarden, M., Andersen, C.L., Frederiksen, H., . . . Abildgaard, N. (2020). Strategies to improve patient-reported outcome completion rates in longitudinal studies. Quality of Life Research, 29(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02304-8

Osoba, D. (1994). Lessons learned from measuring health-related quality of life in oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 12(3), 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1994.12.3.608

Padala, S.A., Barsouk, A., Barsouk, A., Rawla, P., Vakiti, A., Kolhe, R., . . . Ajebo, G.H. (2021). Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma. Medical Sciences, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci9010003

Postma, T.J., Aaronson, N.K., Heimans, J.J., Muller, M.J., Hildebrand, J.G., Delattre, J.Y., . . . Lucey, R. (2005). The development of an EORTC quality of life questionnaire to assess chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: The QLQ-CIPN20. European Journal of Cancer, 41(8), 1135–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.012

Rajkumar, S.V. (2020). Multiple myeloma: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification and management. American Journal of Hematology, 95(5), 548–567. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.25791

Rapkin, B.D., Garcia, I., Michael, W., Zhang, J., & Schwartz, C.E. (2017). Distinguishing appraisal and personality influences on quality of life in chronic illness: Introducing the quality-of-life appraisal profile version 2. Quality of Life Research, 26(10), 2815–2829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1600-y

Rapkin, B.D., & Schwartz, C.E. (2004). Toward a theoretical model of quality-of-life appraisal: Implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-14

Rapkin, B.D., & Schwartz, C.E. (2019). Advancing quality-of-life research by deepening our understanding of response shift: A unifying theory of appraisal. Quality of Life Research, 28(10), 2623–2630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02248-z

Sawatzky, R. (2019). Relating response shift and cognitive appraisal to measurement validation. Quality of Life Research, 28(10), 2633–2634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02276-9

Schwartz, C.E., & Sprangers, M.A.G. (1999). Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Social Science and Medicine, 48(11), 1531–1548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00047-7

Setyowibowo, H., Yudiana, W., Hunfeld, J.A.M., Iskandarsyah, A., Passchier, J., Arzomand, H., . . . Sijbrandij, M. (2022). Psychoeducation for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast, 62, 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2022.01.005

Sommer, K., Cottone, F., Aaronson, N.K., Fayers, P., Fazi, P., Rosti, G., . . . Efficace, F. (2020). Consistency matters: Measurement invariance of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire in patients with hematologic malignancies. Quality of Life Research, 29(3), 815–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02369-5

Sprangers, M.A.G., Sawatzky, R., & Sébille, V. (2021). Progress in response-shift research needs diverse approaches. Quality of Life Research, 30(12), 3365–3366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-03028-4

Sprangers, M.A.G., & Schwartz, C.E. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science and Medicine, 48(11), 1507–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00045-3

Stead, M., Brown, J., Velikova, G., Kaasa, S., Wisløff, F., Child, J., . . . Selby, P. (1999). Development of an EORTC questionnaire module to be used in health-related quality-of-life assessment for patients with multiple myeloma. British Journal of Haematology, 104(3), 605–611. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01206.x

Taminiau-Bloem, E.F., van Zuuren, F.J., Koeneman, M.A., Rapkin, B.D., Visser, M.R.M., Koning, C.C.E., & Sprangers, M.A.G. (2010). A “short walk” is longer before radiotherapy than afterwards: A qualitative study questioning the baseline and follow-up design. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-69

Vanier, A., Oort, F.J., McClimans, L., Ow, N., Gulek, B.G., Böhnke, J.R., . . . Mayo, N. (2021). Response shift in patient-reported outcomes: Definition, theory, and a revised model. Quality of Life Research, 30(12), 3309–3322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02846-w

van Rijn, T. (2009). A physiatrist’s view of response shift. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(11), 1191–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.023

van Roij, J., Kieffer, J.M., van de Poll-Franse, L., Husson, O., Raijmakers, N.J.H., & Gelissen, J. (2022). Assessing measurement invariance in the EORTC QLQ-C30. Quality of Life Research, 31(3), 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02961-8

Wang, Y., Lin, Y., Chen, J., Wang, C., Hu, R., & Wu, Y. (2020). Effects of Internet-based psycho-educational interventions on mental health and quality of life among cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(6), 2541–2552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05383-3

Ware, J.E., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S.D. (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003

Wisløff, F., Eika, S., Hippe, E., Hjorth, M., Holmberg, E., Kaasa, S., . . . Westin, J. (1996). Measurement of health-related quality of life in multiple myeloma. British Journal of Haematology, 92(3), 604–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.352889.x

World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053