Advances in Treatment and Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cohort Study of Older Adult Survivors of Breast Cancer

Objectives: To determine whether there are differences in the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of older adult survivors of breast cancer (BC) diagnosed in different time periods and to gain insight into whether advances in BC treatment have improved HRQOL.

Sample & Setting: Three cohorts of older adult survivors of BC diagnosed before 1995, from 1996 to 2005, and from 2006 to 2015 were examined using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare Health Outcomes Survey linked databases.

Methods & Variables: HRQOL was measured using the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey. Mean cohort HRQOL scores were compared using analysis of variance, then multivariate regression models were used to examine the effects of cohort membership and covariates on mental and physical HRQOL.

Results: Adjusted mean HRQOL scores trended significantly lower with each successive cohort. Higher comorbidity count and increased functional limitations were negatively associated with HRQOL, and income, education level, and better general health perceptions were positively associated with HRQOL.

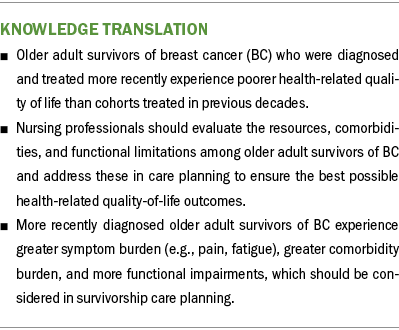

Implications for Nursing: Regardless of time since diagnosis, older survivors of BC are at risk for poor HRQOL and should be regularly assessed. Maximizing HRQOL requires consideration of the survivor’s resources, comorbidities, and functional limitations when planning care.

Jump to a section

In 2020, there were 2.3 million women diagnosed with breast cancer (BC) and 685,000 related deaths globally (World Health Organization, 2023). By the end of 2020, there were 7.8 million women alive who had been diagnosed with BC in the past five years, making it the most prevalent cancer in the world (World Health Organization, 2023). In the United States, BC is the second most common cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women (American Cancer Society, 2023a). About 90% of survivors of BC will be alive five years after diagnosis (American Cancer Society, 2023b). Advances in treatment have led to improved survival rates for individuals with BC; coupled with the rise in the number of older adults, the number of older adult survivors of BC is predicted to increase significantly in the coming years (Heer et al., 2020). However, the impact of treatment advances on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in older adult survivors of BC is unclear.

HRQOL is a multidimensional and subjective construct reflecting an individual’s overall sense of well-being relative to their health (Bakas et al., 2012). Survivors of BC experience significant impairments to HRQOL (Maly et al., 2015), particularly in the physical domain (Trentham-Dietz et al., 2008); these impairments may persist for at least two to five years postdiagnosis (Maly et al., 2015; Trentham-Dietz et al., 2008). Impairments to HRQOL may be more likely to persist in survivors of later-stage BC (Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2023). In cohorts of older adult survivors of BC, findings related to trajectories of HRQOL over time are mixed. For example, Ganz et al. (2003) found that physical and mental HRQOL declined significantly during the 12-month period following a diagnosis of BC in older adults. In contrast, Jones et al. (2015) found that older adult survivors of BC reported significant declines in physical HRQOL 10 or more years postdiagnosis but steady improvements in mental HRQOL from the time of diagnosis, although mental HRQOL did not return to precancer levels even 10 years postdiagnosis.

Certain characteristics may place survivors of BC at higher risk for poor HRQOL; negative associations have been found between HRQOL and lower household income (Neuner et al., 2014), higher number of comorbidities (Ganz et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2007; Maly et al., 2015; Neuner et al., 2014; Yeom & Heidrich, 2013), and greater symptom burden (Jones et al., 2015; Reeve et al., 2009; Robb et al., 2007; Stover et al., 2014). Of note, these characteristics are more likely to be present among older adult survivors of BC, placing them at higher risk for experiencing impaired HRQOL. Symptoms may be more significant among older adult survivors because of age-related complications (e.g., functional declines, obesity, falls), the presence of comorbidities, and polypharmacy (Biganzoli et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2020; Kent et al., 2016; Mohamed et al., 2020). In addition, older adult survivors may be at higher risk for experiencing more significant adverse effects related to cancer and its treatments because older adults have reduced functional reserves and are therefore more likely to experience unwanted cancer-related symptoms and toxicities (Bhatt, 2019; Muss et al., 2007; Versteeg et al., 2014).

Age and age at diagnosis of BC have been consistently found to be associated with HRQOL, but the nature of these relationships remains unclear. For example, older age and older age at the time of diagnosis of BC have been associated with significantly better mental (Ganz et al., 1998) and overall HRQOL when compared to younger counterparts (Champion et al., 2014; Ferrell et al., 1998; Jones et al., 2015; Kwan et al., 2010; Maly et al., 2015; Pinheiro et al., 2017; Sammarco, 2009). In contrast, older age and older age at the time of diagnosis have also been associated with significantly worse physical HRQOL (Cimprich et al., 2002; Ganz et al., 1998) and, in one study, overall HRQOL (Lu et al., 2009).

Key advances in personalized medicine suggest that HRQOL for survivors of BC may have changed. Prior to 1995, the understanding of BC biology was limited. Radical surgical procedures were standard, and clinical trials for neoadjuvant chemotherapies had just begun (Ades et al., 2017; Keelan et al., 2021). The 1980s brought important advances in supportive care, such as effective antiemetics and analgesics that improved control of adverse effects and sought to improve HRQOL (Hortobagyi, 2020). The 1990s saw the origins of the clinical applications of gene expression profiling, along with the rapid clinical development of new cytotoxic drugs and bisphosphonates used in symptom management of metastatic BC (Ades et al., 2017; Hortobagyi, 2020). The 2000s brought a shift to less radical surgeries combined with radiation therapy. In addition, the Human Genome Project was completed, which marked the beginning of personalized oncology treatment. In 2005, pharmacologic research began to shift to the development of immunotherapies and targeted therapies. However, these treatments produced different side effects and symptom profiles (Hortobogayi, 2020) that posed new challenges in nursing care.

Although modern clinical therapies aim to enhance the effectiveness of cancer treatment, it is unclear whether these advances have improved or reduced HRQOL in older adult survivors. In addition, older adults are often underrepresented in cancer clinical trials; therefore, little is known about how advances in cancer treatment may interact with comorbidities common to this population (Bluethmann et al., 2016; DeSantis et al., 2019; Versteeg et al., 2014).

Purpose

Older adults may differ from other groups of survivors of BC, and the existing literature is inconclusive about the demographic and clinical factors that may affect HRQOL. In addition, it is unclear how the HRQOL or correlates of HRQOL of this group persist or change over time in relation to recent treatment advances. As such, the purposes of this cohort study were to address these gaps in the literature by determining whether advances in cancer care in the past several decades have resulted in changes in HRQOL or the demographic and clinical factors associated with HRQOL among a national sample of older adult BC survivors. The study aimed to (a) compare HRQOL among three cohorts of older adult survivors of BC diagnosed a decade apart and (b) explore relationships between HRQOL and demographic and clinical variables among these three cohorts of survivors.

Methods

Design, Data Collection, Sample, and Instruments

A retrospective cohort design was used to compare the HRQOL of older adult survivors of BC diagnosed during different time periods. Approval from the Villanova University Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to study onset.

This study used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (MHOS) linked dataset available from the National Cancer Institute. Every year since 1998, a random sample of participants with Medicare Advantage plans has been selected to receive the MHOS and has been surveyed again two years later. The MHOS consists of questions about demographics, health diagnoses, functional status, symptoms, health perceptions, and the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) to measure HRQOL. The linked SEER database contains information on cancer type, stage, time since diagnosis, and certain treatments (Kent et al., 2016).

MHOS respondents through 2015, the most recent year of SEER-MHOS data available to investigators, were sampled. Participants in the sample met the following inclusion criteria: (a) being aged at least 50 years and (b) having been diagnosed with BC prior to at least one MHOS survey. Participants were excluded if they had been diagnosed with another form of cancer (e.g., lung, ovarian) prior to or simultaneously with their diagnosis of BC to maintain the focus on BC survivorship. Although the MHOS began collecting data in 1998, information on cancer diagnosis and treatment was available for earlier time periods through the SEER database, so those who were diagnosed with BC before 1998 were able to be included in this sample.

HRQOL, the outcome measure in this study, was examined using the VR-12. The VR-12 is a 12-item scale with a physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). In addition to measuring physical and mental HRQOL, the VR-12 provides subscale scores for general health, physical functioning, physical role limitations, emotional role limitations, pain, social functioning, and vitality. The VR-12 was initially developed for use in the veteran population and adapted from the SF-36® and SF-12® (Selim et al., 2009). The MCS and PCS scores indicate the individual’s mental and physical HRQOL, respectively, with higher scores reflecting better HRQOL. The MCS and PCS raw scores undergo t-score transformation and are normed to the U.S. population to calculate the final MCS and PCS scores. Cronbach’s alpha for the VR-12 in this sample was 0.9 for the total scale, 0.85 for the PCS, and 0.84 for the MCS.

Theoretical Framework and Study Variables

The revision by Ferrans et al. (2005) of Wilson and Cleary’s Model of HRQOL was used to guide the development of and variable selection for this study. This model posits that characteristics of both the individual and the environment influence biologic function, symptoms, functional status, and general health perceptions, which culminate to influence overall HRQOL. Individual and environmental characteristics examined in this study were the demographic factors of age at diagnosis, gender, race, income, education level, and marital status. Aspects of biologic function explored in this study were the following cancer-specific data obtained from the SEER database: cancer stage, BC recurrence, cancer diagnosis at another site after BC diagnosis, previous surgical cancer intervention, and previous radiation therapy. Other biologic function variables used in this study were the presence of comorbid conditions; on the MHOS, survivors were asked to identify whether they had been diagnosed with or treated for specific common comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and inflammatory bowel disease). This study also measured symptoms, functional status, and general health perceptions via participant self-report on the MHOS to assess HRQOL. For symptoms, pain and fatigue (vitality) were examined for each cohort as part of physical HRQOL. For function, self-reported functional limitations were examined. General health perceptions were examined using a question on general health perceptions from the MHOS. MCS and PCS scores from the VR-12 were used to measure mental and physical HRQOL, respectively.

Data Analysis

StataMP, version 12.0, was used for all statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed, including frequencies and percentages for binary or categorical variables and means and SDs for continuous variables. Mean scores for mental and physical HRQOL, along with mean scores for general health, physical functioning, physical role limitations, emotional role limitations, pain, social functioning, and vitality, were computed for each cohort. Listwise deletion was used to address missing data because only a small percentage (less than 10%) of data on key outcomes of interest was missing (Allison, 1999). A one-way analysis of variance was conducted to compare the unadjusted mean scores. Finally, multivariate regression models for mental and physical HRQOL were used to explore the effects of cohort membership (i.e., when a participant was diagnosed), demographic characteristics (age, education level, income, marital status, and race), biologic function (cancer stage, surgery, radiation therapy, recurrence, and comorbidity count), functional status, and general health perception on HRQOL.

Results

Sample Characteristics

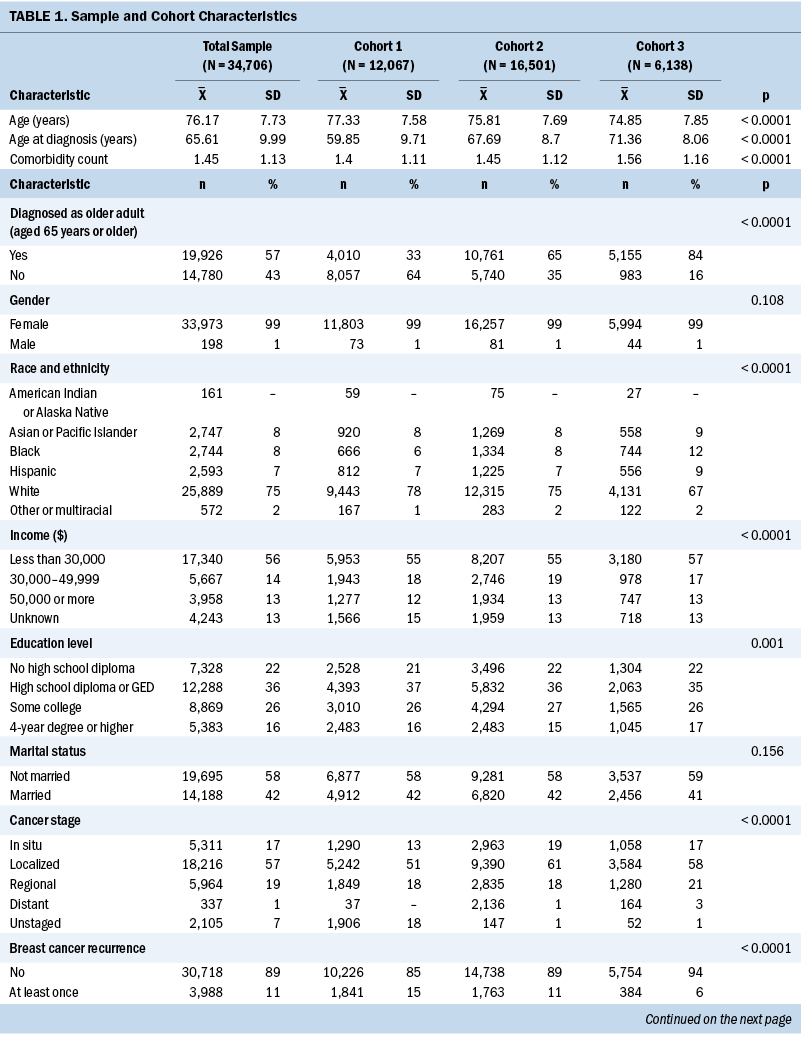

The total sample for this analysis consisted of 34,706 participants, of which 12,067 (35%) received their initial BC diagnosis before 1995 (cohort 1), 16,501 (48%) were diagnosed between 1995 and 2004 (cohort 2), and 6,138 (18%) were diagnosed between 2005 and 2013 (cohort 3). The average age of participants was 76.17 years, and the average age at diagnosis was 65.61 years, and participants had survived for an average of nine years after. More than half of the participants were White (75%), female (99%), had an annual income of less than $30,000 (56%), had either not finished high school (22%) or had a high school diploma (36%), or were not married (58%) (see Table 1).

There were demographic differences between the cohorts. In particular, the average age at diagnosis was younger for cohorts 1 (59.85 years) and 2 (67.69 years) than for cohort 3 (71.36 years). This indicates that the members of cohort 1 were more removed from their initial cancer diagnosis at the time of the survey than members of cohorts 2 and 3 (p < 0.0001). Correspondingly, the likelihood of being diagnosed as an older adult (age 65 years or older) was much higher for cohorts 2 and 3 than for cohort 1 (p < 0.0001). Other trends in the demographic data reflect larger trends in the U.S. population, with increases in racial diversity (p < 0.0001) and education level (p = 0.001) seen in cohorts 2 and 3 versus cohort 1.

In terms of clinical factors, those in earlier cohorts were more likely to experience BC recurrence or a diagnosis of cancer at another site (p < 0.0001). The burden of comorbidity was greater in cohorts 2 and 3, with higher rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared to cohort 1 (p < 0.0001). Overall, general health perception was poorer in cohorts 2 and 3, with participants in these cohorts more likely to rate their health as poor or fair compared to participants in cohort 1 (p < 0.0001).

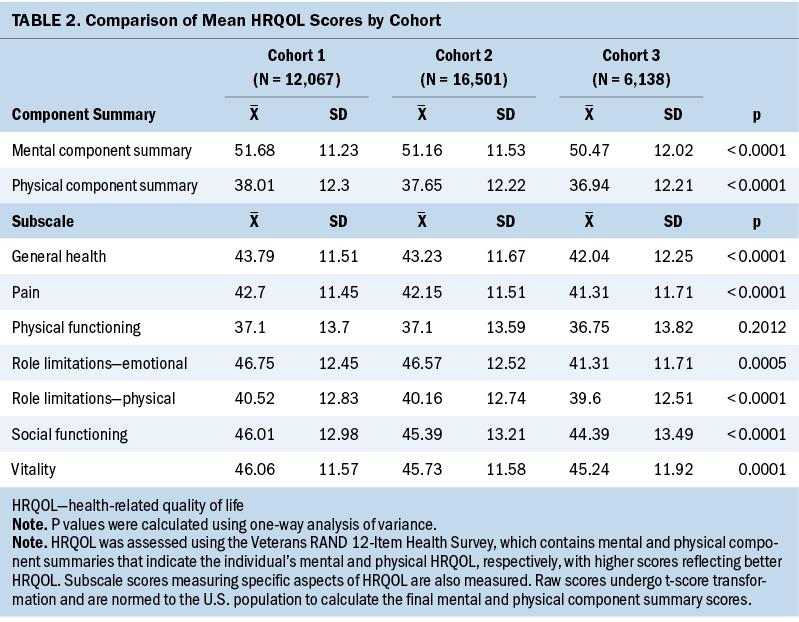

Comparison of HRQOL Between Cohorts

There were significant differences by cohort in mental and physical HRQOL and all VR-12 subscales (p < 0.001) except physical functioning (p = 0.2012). HRQOL trended lower with each cohort, which means that the mental and physical HRQOL of cohort 3 were slightly worse than those of cohort 2, which were slightly worse than those of cohort 1 (see Table 2). The regression analysis confirmed that this relationship held true for mental and physical HRQOL even when adjusting for demographic and clinical covariates.

Relationships Between HRQOL and Demographic and Clinical Variables

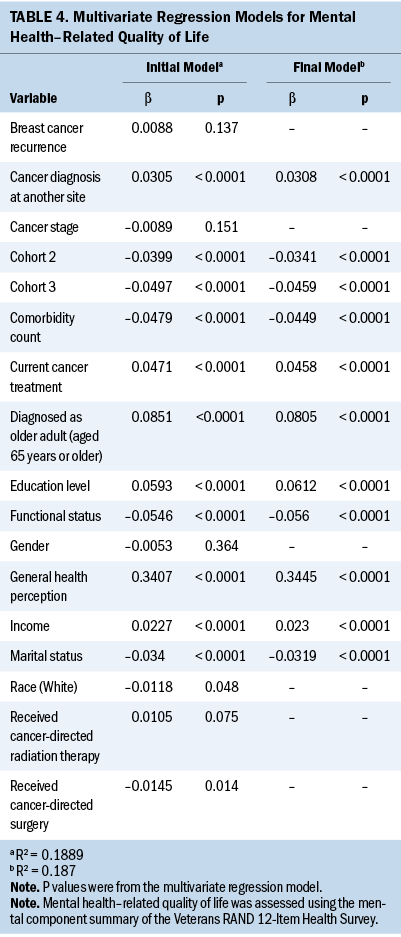

Tables 3 and 4 detail findings from the multivariate regression analyses for physical HRQOL (PCS scores) and mental HRQOL (MCS scores), respectively. Belonging to cohorts 2 or 3, greater education level, higher comorbidity count, White race, and increased functional limitations were negatively associated with physical HRQOL, and higher annual income, having undergone cancer-directed surgery, and better general health perception were positively associated with physical HRQOL (R2 = 0.7311). Belonging to cohorts 2 or 3, not being married or partnered, greater comorbidity count, and increased functional limitations were negatively associated with mental HRQOL, and older age at diagnosis (65 years or older), higher annual income, greater education level, experiencing a second cancer diagnosis, absence of current cancer treatment, and better general health perception were positively associated with mental HRQOL (R2 = 0.187).

Discussion

Exploring differences in HRQOL, demographics, and clinical variables among these three cohorts of older adult survivors of BC a decade apart provides a unique view of HRQOL experienced in different time periods. Overall, physical and mental HRQOL differed significantly among the three cohorts of older adult survivors of BC. Of note, being in cohorts 2 or 3 (those more recently diagnosed and treated) was associated with significantly poorer physical and mental HRQOL. Differences in HRQOL scores were more pronounced in the physical domain compared to the mental domain. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and functional limitations significantly affected physical and mental HRQOL.

Contrary to expectations, survivors of BC who were diagnosed and treated more recently had lower HRQOL than those diagnosed and treated in earlier decades. This may be related to several factors, such as differences in treatment modalities, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, or changes in overall patient profile. Although the effects of treatments like breast surgery (mastectomy or lumpectomy), traditional chemotherapies, and radiation therapy on symptoms and HRQOL have been relatively well studied, the emergence of newer modalities of cancer treatment (e.g., immunotherapy, targeted therapies) that produce different toxicities, adverse effects, and symptom profiles may have longer-term impacts on HRQOL that are currently not well understood. The earlier cohorts were diagnosed at younger ages, on average, and may have experienced greater rebounds in their HRQOL in the longer time since their initial diagnosis. Although this study adjusted for age at diagnosis in the multivariate regression model, there may be an interaction between age at diagnosis and the trajectory of HRQOL following diagnosis and treatment that requires additional exploration. This study also suggests that broader trends, such as growing obesity and associated comorbidities (e.g., diabetes) among older adults, may affect HRQOL as well. Nurses working with older adult survivors of BC are treating sicker and more complex patients today than in previous years (Vissers et al., 2013). The difference in physical HRQOL scores across the three cohorts was clinically relevant, suggesting that even nine years after a BC diagnosis, clinicians must assess for substantial impairments to HRQOL in the physical domain. This finding is consistent with Jones et al. (2015), who also found that older adult survivors of BC reported significant declines in physical HRQOL 10 or more years postdiagnosis.

Physical HRQOL scores were lower than mental HRQOL scores, consistent with previous research, suggesting that older adult survivors maintain mental resilience when facing physical declines. However, those with fewer external and internal resources, such as survivors with a lower income and education level or those with greater functional limitations, are at higher risk for experiencing poor HRQOL in both dimensions. This is consistent with the findings of Neuner et al. (2014), as well as Lu et al. (2007), who also reported a positive association between household income and physical and mental HRQOL. Nurses should assess for financial stress among older adult survivors of BC and consider how it might affect the plan of care. Education level is likely to influence income and may also be associated with health literacy, which should be taken into consideration when planning nursing care.

A higher number of comorbidities was associated with reduced physical and mental HRQOL in this study, which supports the existing literature (Durá-Ferrandis et al., 2017; Ganz et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2007; Maly et al., 2015; Neuner et al., 2014). Older adult survivors of BC are likely to present with multiple comorbidities; these comorbidities and associated treatments can negatively affect HRQOL and interact with cancer-related treatment and symptoms. Similarly, functional impairment, which is more common among older adults, was linked to worse physical and mental HRQOL. Holistic assessments and individualized treatment plans are necessary for these older adult survivors. A geriatrician or geriatric nurse practitioner can be an invaluable resource in planning care.

Older adult survivors from cohorts 1 and 2 were more likely to experience BC recurrence or receive a diagnosis of another type of cancer. It is unclear why experiencing a diagnosis of another type of cancer was associated with higher mental HRQOL. This may be related to post-traumatic growth or to receiving treatment for the secondary cancer diagnosis that improves overall symptom burden. Health anxiety is very common among cancer survivors, with many reporting significant anxiety associated with checkups (Lovelace et al., 2019). It is possible that when “the worst” has happened, anxiety levels decrease. Additional research is needed to explore the experiences and HRQOL of survivors who are experiencing a secondary cancer diagnosis.

Limitations

One of the primary strengths of this study is that it capitalizes on the availability of a nationally representative database. As with any secondary data analysis, the study plan was limited to the data collected. A limitation of the SEER-MHOS dataset is that it contains data only from Medicare Advantage plan participants and excludes Medicare fee-for-service participants. Medicare Advantage plan participants have been shown to be healthier on average than Medicare fee-for-service participants and to report higher HRQOL on average (Riley, 2000). In addition, the SEER-MHOS dataset does not include complete treatment variables. For example, chemotherapy data are not included, so this study was unable to account for chemotherapy as a treatment variable in analyses. In addition, certain relevant symptoms, such as pain and vitality, were measured using the VR-12 and as such were highly correlated with HRQOL scores, which prevented the inclusion of these symptoms in the regression analyses.

Implications for Nursing Practice and Nursing Research

HRQOL is a key person-centered clinical outcome that may not be regularly or thoroughly assessed in clinical practice. Nurses should assess HRQOL regularly across the survivorship trajectory. Findings from this study underscore the importance of nursing assessments of HRQOL in the physical domain nearly 10 years postdiagnosis of BC. Nurses should also assess demographic and clinical factors in survivors who are at risk for poor HRQOL outcomes and should use valid and reliable instruments to do so. In this study, the VR-12 questionnaire was used to assess mental and physical HRQOL; this tool is available in electronic and paper forms and has been translated into multiple languages to increase accessibility. Nurses can use the VR-12 to facilitate assessments of HRQOL in the clinical setting, which can enable them to focus on areas of concern, such as functional limitations, pain, fatigue, or depression.

When assessing HRQOL and creating a plan of care, the nurse should also consider assessing factors that are related to mental and physical HRQOL. For example, this study found that education level was associated with HRQOL among older adult survivors of BC. Although education level may be relatively static in the older adult population, the nurse should consider assessing for health literacy and adjusting teaching materials to ensure patient understanding. Similarly, the nurse should assess the effects of comorbidities, which are highly prevalent in the older adult population. Comorbidities may be triggered by cancer treatment (e.g., cardiovascular or lung disease following intensive radiation therapy or chemotherapy regimens) but may also be preexisting or associated with common risk factors (e.g., smoking). Comorbid conditions are likely to worsen symptoms related to cancer or its treatments (e.g., fatigue, pain) and may complicate symptom management, which warrants additional research.

It is essential for nursing professionals to evaluate comorbidities, functional limitations, and resources among older adult survivors of BC in care planning to ensure the best possible HRQOL outcomes. Future research is needed to determine the effects of current oncology treatment regimens on HRQOL. Prospective exploration of the trajectory of HRQOL and its correlates over time is necessary to provide a more detailed view of changes in these relationships to fully understand this phenomenon. This knowledge would inform the development and testing of evidence-based management protocols to address less-studied adverse effects and symptoms associated with existing and newer cancer treatments (e.g., immunotherapies, targeted therapies).

Conclusion

Despite advances in oncology treatment regimens in the past few decades, significant improvements were not observed in the HRQOL of more recently diagnosed cohorts of older adult survivors of BC in this study after adjusting for demographic and clinical variables. In fact, mental and physical HRQOL trended significantly lower in each successive cohort in this study, suggesting that more recently diagnosed survivors of BC experience worse HRQOL. Cohort membership (e.g., when a participant was diagnosed), education level, comorbidity count, functional limitations, and general health perception were significantly associated with mental and physical HRQOL. Findings from this study suggest that HRQOL must be regularly assessed in older adult survivors of BC. To maximize HRQOL, nurses should perform holistic assessments that include survivor income and financial security, education, comorbidities, functional limitations, and previous and current cancer treatments, and they should tailor survivorship care plans to each survivor’s specific needs.

About the Authors

Sherry A. Burrell, PhD, RN, CNE, is an associate professor, Gabrielle E. Sasso, BSN, RN, is a nursing student, and Meredith MacKenzie Greenle, PhD, RN, CRNP, CNE, is an associate professor, all in the M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. This research was supported, in part, by the Villanova University Summer Research Grant and the Villanova University Small Research Grant awarded to Burrell and Greenle. Burrell and Greenle contributed to the conceptualization and design and provided the analysis. Greenle provided statistical support. All authors completed the data collection and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Burrell can be reached at sherry.burrell@villanova.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted October 2022. Accepted May 16, 2023.)

References

Ades, F., Tryfonidis, K., & Zardavas, D. (2017). The past and future of breast cancer treatment—From the papyrus to individualised treatment approaches. Ecancermedicalscience, 11, 746. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2017.746

Allison, P.D. (1999). Multiple regression: A primer. Pine Forge Press.

American Cancer Society. (2023a). Key statistics for breast cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-…

American Cancer Society. (2023b). Survival rates for breast cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/understanding-a-breast-canc…

Bakas, T., McLennon, S.M., Carpenter, J.S., Buelow, J.M., Otte, J.L., Hanna, K.M., . . . Welch, J.L. (2012). Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-134

Bhatt, V.R. (2019). Cancer in older adults: Understanding cause and effects of chemotherapy-related toxicities. Future Oncology, 15(22), 2557–2560. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2019-0159

Biganzoli, L., Battisti, N.M.L., Wildiers, H., McCartney, A., Colloca, G., Kunkler, I.H., . . . Brain, E.G.C. (2021). Updated recommendations regarding the management of older patients with breast cancer: A joint paper from the European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) and the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). Lancet Oncology, 22(7), e327–e340. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30741-5

Bluethmann, S.M., Mariotto, A.B., & Rowland, J.H. (2016). Anticipating the “silver tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 25(7), 1029–1036. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133

Champion, V.L., Wagner, L.I., Monahan, P.O., Daggy, J., Smith, L., Cohee, A., . . . Sledge, G.W., Jr. (2014). Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer, 120(15), 2237–2246. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28737

Cimprich, B., Ronis, D.L., & Martinez-Ramos, G. (2002). Age at diagnosis and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Practice, 10(2), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.102006.x

DeSantis, C.E., Ma, J., Gaudet, M.M., Newman, L.A., Miller, K.D., Goding Sauer, A., . . . Siegel, R.L. (2019). Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(6), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21583

Durá-Ferrandis, E., Mandelblatt, J.S., Clapp, J., Luta, G., Faul, L., Kimmick, G., . . . Hurria, A. (2017). Personality, coping, and social support as predictors of long-term quality-of-life trajectories in older breast cancer survivors: CALGB protocol 369901 (Alliance). Psycho-Oncology, 26(11), 1914–1921. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4404

Ferrans, C.E., Zerwic, J.J., Wilbur, J.E., & Larson, J.L. (2005). Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37(4), 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x

Ferrell, B.R., Grant, M.M., Funk, B.M., Otis-Green, S.A., & Garcia, N.J. (1998). Quality of life in breast cancer survivors: Implications for developing support services. Oncology Nursing Forum, 25(5), 887–895. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9644705

Ganz, P.A., Guadagnoli, E., Landrum, M.B., Lash, T.L., Rakowski, W., & Silliman, R.A. (2003). Breast cancer in older women: Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in the 15 months after diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21(21), 4027–4033. http://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.08.097

Ganz, P.A., Rowland, J.H., Desmond, K., Meyerowitz, B.E., & Wyatt, G.E. (1998). Life after breast cancer: Understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16(2), 501–514. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9469334

Heer, E., Harper, A., Escandor, N., Sung, H., McCormack, V., & Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. (2020). Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: A population-based study. Lancet Global Health, 8(8), e1027–e1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30215-1

Hortobagyi, G.N. (2020). Breast cancer: 45 years of research and progress. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(21), 2454–2462. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00199

Jones, D., di Martino, E., Hatton, N.L., Surr, C., de Wit, N., & Neal, R.D. (2020). Investigating cancer symptoms in older people: What are the issues and where is the evidence? British Journal of General Practice, 70(696), 321–322. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X710789

Jones, S.M.W., LaCroix, A.Z., Li, W., Zaslavsky, O., Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Weitlauf, J., . . . Danhauer, S.C. (2015). Depression and quality of life before and after breast cancer diagnosis in older women from the Women’s Health Initiative. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 9(4), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0438-y

Keelan, S., Flanagan, M., & Hill, A.D.K. (2021). Evolving trends in surgical management of breast cancer: An analysis of 30 years of practice changing papers. Frontiers in Oncology, 11, 622621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.622621

Kent, E.E., Malinoff, R., Rozjabek, H.M., Ambs, A., Clauser, S.B., Topor, M.A., . . . DeMichele, K. (2016). Revisiting the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results cancer registry and Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (SEER-MHOS) linked data resource for patient-reported outcomes research in older adults with cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(1), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13888

Kwan, M.L., Ergas, I.J., Somkin, C.P., Quesenberry, C.P., Jr., Neugut, A.I., Hershman, D.L., . . . Kushi, L.H. (2010). Quality of life among women recently diagnosed with invasive breast cancer: The Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 123(2), 507–524. http://www.doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-0764-8

Lovelace, D.L., McDaniel, L.R., & Golden, D. (2019). Long-term effects of breast cancer surgery, treatment, and survivor care. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 64(6), 713–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13012

Lu, W., Cui, Y, Chen, X., Zheng, Y., Gu, K., Cai, H., . . . Shu, X.-O. (2009). Changes in quality of life among breast cancer patients three years post-diagnosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 114(2), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-008-0008-3

Lu, W., Cui, Y., Zheng, Y., Gu, K., Cai, H., Li, Q., . . . Shu, X.O. (2007). Impact of newly diagnosed breast cancer on quality of life among Chinese women. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 102(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-006-9318-5

Maly, R.C., Liu, Y., Liang, L.-J., & Ganz, P.A. (2015). Quality of life over 5 years after a breast cancer diagnosis among low-income women: Effects of race/ethnicity and patient-physician communication. Cancer, 121(6), 916–926. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29150

Mohamed, M.R., Ramsdale, E., Loh, K.P., Arastu, A., Xu, H., Obrecht, S., . . . Mohile, S.G. (2020). Associations of polypharmacy and inappropriate medications with adverse outcomes in older adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncologist, 25(1), e94–e108. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0406

Muss, H.B., Berry, D.A., Cirrincione, C., Budman, D.R., Henderson, I.C., Citron, M.L., . . . Hudis, C.A. (2007). Toxicity of older and younger patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: The cancer and leukemia group B experience. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(24), 3699–3704. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9710

Neuner, J.M., Zokoe, N., McGinley, E.L., Pezzin, L.E., Yen, T.W.F., Schapira, M.M., & Nattinger, A.B. (2014). Quality of life among a population-based cohort of older patients with breast cancer. Breast, 23(5), 609–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2014.06.002

Pat-Horenczyk, R., Kelada, L., Kolokotroni, E., Stamatakos, G., Dahabre, R., Bentley, G., . . . Roziner, I. (2023). Trajectories of quality of life among an international sample of women during the first year after the diagnosis of early breast cancer: A latent growth curve analysis. Cancers, 15(7), 1961. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15071961

Pinheiro, L.C., Tan, X., Olshan, A.F., Wheeler, S.B., Reeder-Hayes, K.E., Samuel, C.A., & Reeve, B.B. (2017). Examining health-related quality of life patterns in women with breast cancer. Quality of Life Research, 26(7), 1733–1743.

Reeve, B.B., Potosky, A.L., Smith, A.W., Han, P.K., Hays, R.D., Davis, W.W., . . . Clauser, S.B. (2009). Impact of cancer on health-related quality of life of older Americans. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 101(12), 860–868.

Riley, G. (2000). Two-year changes in health and functional status among elderly Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs and fee-for-service. Health Services Research, 35(5), 44–59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1383594/pdf/16148951.pdf

Robb, C., Haley, W.E., Balducci, L., Extermann, M., Perkins, E.A., Small, B.J., & Mortimer, J. (2007). Impact of breast cancer survivorship on quality of life in older women. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 62(1), 84–91.

Sammarco, A. (2009). Quality of life of breast cancer survivors: A comparative study of age cohorts. Cancer Nursing, 32(5), 347–358. https://www.doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819e23b7

Selim, A.J., Rogers, W., Fleishman, J.A., Qian, S.X., Fincke, B.G., Rothendler, J.A., & Kazis, L.E. (2009). Updated U.S. population standard for the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12). Quality of Life Research, 18(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9418-2

Stover, A.M., Mayer, D.K., Muss, H., Wheeler, S.B., Lyons, J.C., & Reeve, B.B. (2014). Quality of life changes during the pre- to postdiagnosis period and treatment-related recovery time in older women with breast cancer. Cancer, 120(12), 1881–1889. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28649

Trentham-Dietz, A., Sprague, B.L., Klein, R., Klein, B.E.K., Cruickshanks, K.J., Fryback, D.G., & Hampton, J.M. (2008). Health-related quality of life before and after a breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 109(2), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-007-9653-1

Versteeg, K.S., Konings, I.R., Lagaay, A.M., van de Loosdrecht, A.A., & Verheul, H.M.W. (2014). Prediction of treatment-related toxicity and outcome with geriatric assessment in elderly patients with solid malignancies treated with chemotherapy: A systematic review. Annals of Oncology, 25(10), 1914–1918. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu052

Vissers, P.A., Thong, M.S., Pouwer, F., Zanders, M.M., Coebergh, J.W., & van de Poll-Franse, L.V. (2013). The impact of comorbidity on health-related quality of life among cancer survivors: Analyses of data from the PROFILES registry. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice, 7(4), 602–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0299-1

World Health Organization. (2023). Breast cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer

Yeom, H.-E., & Heidrich, S.M. (2013). Relationships between three beliefs as barriers to symptom management and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40(3), E108–E118. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.ONF.E108-E118