Understanding Men’s Experiences With Prostate Cancer Stigma: A Qualitative Study

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences and perspectives of men who have had prostate cancer to better understand the effect of prostate cancer and associated stigmas on men in the Canadian province Newfoundland and Labrador (NL).

Participants & Setting: Eleven men from NL who have had prostate cancer participated in semistructured interviews exploring their perspectives and experiences of prostate cancer and stigma.

Methodologic Approach: A social–ecological framework was used to understand experiences from different domains. Interviews were analyzed using Lichtman’s three Cs approach. Analysis focused on establishing themes of the participants’ lived experience of prostate cancer and related stigma.

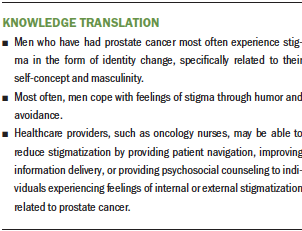

Findings: Participants described how emasculating a prostate cancer diagnosis can feel. They identified ways prostate cancer negatively affected their behaviors and sense of self, described coping with the diagnosis and different strategies, and talked about broader system change required to address prostate cancer stigma. Participants expressed a need for additional support from healthcare providers (HCPs).

Implications for Nursing: HCPs, such as oncology nurses, may be able to reduce stigmatization by providing patient navigation, improving information delivery, or providing psychosocial counseling to individuals experiencing feelings of internal or external stigmatization related to prostate cancer.

Jump to a section

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in Canada, with about 21,000 new cases diagnosed annually (Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee [CCSAC], 2018). Because of modern medical advances, most men survive prostate cancer but face long-lasting and late-appearing side effects (CCSAC, 2018; Ettridge et al., 2019; Weber & Sherwill-Navarro, 2005), which can be physical (e.g., fatigue, sexual dysfunction, incontinence) or psychological (e.g., stress, anxiety, depression) (Weber & Sherwill-Navarro, 2005). In addition to the negative side effects, an increasing number of prostate cancer survivors are facing a new kind of challenge—stigma.

Stigma, which refers to a human attribute that is devalued in society (Goffman, 1963), is not new to cancer. In general, cancer has been identified as a highly stigmatized condition, often because of its association with death, changes in one’s body image, or blame and shame (Else-Quest et al., 2009; Mosher & Danoff-Berg, 2007). Evidence has shown that prostate cancer survivors can experience adverse consequences, such as depression and anxiety, making cancer-related stigma a growing topic in prostate cancer–related research (Koller et al., 1996). To this point, most cancer stigma research has focused on lung cancer, because there are strong feelings of blame and shame caused by the belief that one has caused his or her own disease (Else-Quest et al., 2009); however, research has begun to explore the effects of stigma on other types of cancer, such as prostate cancer.

To date, research on prostate cancer stigma has identified that perceptions of the disease as self-inflicted can lead to internalized stigma (Else-Quest et al., 2009; Lebel & Devins, 2008; Vogel et al., 2011). Internalized stigma, characterized by negative self-perceptions and self-blame, has been shown to impair help-seeking behaviors, reduce men’s willingness to disclose, and increase feelings of social isolation during and following treatment (Ettridge et al., 2019; Kunkel et al., 2000; Pietilä et al., 2016; Winterich et al., 2009). Overall, prostate cancer stigma has been shown to have a negative impact on men’s relationships and overall quality of life (Wood et al., 2017, 2019). Much of the literature suggests that this stigma stems from the negative side effects on sexual organs and function and the challenges these side effects pose to masculinity (Ettridge et al., 2019). Studies have suggested that men who have had prostate cancer experience internalized stigma as well as stigmatization from others who are close to them, such as family or community members; however, the topic of stigma remains underexplored within nursing literature (Ahmad et al., 2018). Prostate Cancer Canada has identified stigma as an area requiring research, suggesting that the stigma around prostate cancer can lead to poorer outcomes and unnecessary death (Rossi & Bombaci, n.d.). Given the growing awareness about the negative effects of prostate cancer stigma, more research on the experiences of men who have had prostate cancer is needed to support them, their families, and the healthcare system to better respond to their needs.

Purpose

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the experiences and perspectives of prostate cancer survivors living in Newfoundland and Labrador (NL). In Canada, the province of NL has the highest incidence and mortality rates of prostate cancer (CCSAC, 2018); therefore, it was a fitting setting in which to conduct the study. More specifically, the study sought to understand the effect of prostate cancer on men’s lives and their relationships, and the social perceptions and stigmas of living with prostate cancer. A social–ecological framework (McLeroy et al., 1988) was used to organize the interview questions and better understand the experiences of men who have had prostate cancer from different domains. This framework identifies five levels of an individual’s social environment that can affect health and behaviors. These five levels are as follows: intrapersonal (individual factors such as attitudes, behaviors, and self-concepts), interpersonal (social networks such as family, coworkers, and friends), organizational (social institutions and organizations such as schools, workplaces, and hospitals), community (relationships between groups of individuals and organizations within a defined geographic area), and public policy (McLeroy et al., 1988).

Methods

Participants and Setting

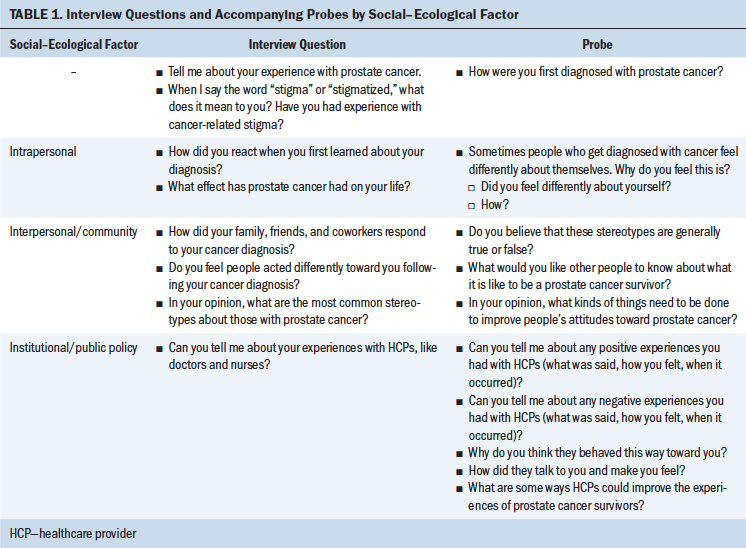

For this study, 11 men from NL who have had prostate cancer and were at a minimum of six months post-treatment (i.e., surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy) were recruited for a semistructured interview. Examples of interview questions and probes are included in Table 1. NL is Canada’s easternmost province and is composed of the island of Newfoundland and the region of Labrador on the northeastern mainland of Canada. In 2019, the population of NL was 521,542, with around 40% of the population of NL living in the capital city of St. John’s (NL Statistics Agency, 2020). The remainder of the population of NL is sparsely dispersed over a large geographic area (NL Statistics Agency, 2020). NL has the highest average age among all Canadian provinces and one of the highest rates of many chronic diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, and some types of cancer (CCSAC, 2018; Public Health Infobase, 2017). Recruitment took place through presentations at local support groups, brochures and posters placed at the local cancer center, a radio interview, and word of mouth. To be included in the study, participants had to be a resident of NL, be aged 18 years or older, have received a diagnosis of prostate cancer and be six months post-treatment, and feel they had experienced stigma related to prostate cancer. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study in person or via telephone before meeting to conduct the interview. Before beginning the interview, informed consent was obtained from each participant. This study was approved by the NL Health Research Ethics Board (file # 20170892).

Methodologic Approach

Interviews were conducted either in person (n = 10) or via telephone (n = 1) and were audio recorded. Interviews lasted from 60 to 120 minutes. Participants were asked to choose a pseudonym to be used to protect their anonymity within the presentation of the results. Participants were asked about their perspectives and experiences living with prostate cancer, as well as their relationships with family members and the healthcare system. A male researcher and a female researcher (R.B. and E.C., respectively) conducted the first interview. After debriefing the interview, the research team decided that having a woman present could negatively influence data collection because the participant appeared uneasy, glancing nervously at the female researcher. All other interviews were conducted by R.B.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using Atlas.ti, version 7.5. Two researchers (R.B. and R.C.) analyzed the transcripts using Lichtman’s (2014) three Cs approach. This approach uses an iterative process of coding, categorizing, and conceptualizing to draw meaning from qualitative data. Transcripts were read multiple times by each researcher. Axial coding and structural coding were then applied to analyze the data. Throughout the process, researchers met multiple times to discuss the emerging code list, identify discrepancies in their coding, and confirm data saturation. Codes were then grouped into categories based on commonalities, and major concepts were established from the categories. To establish trustworthiness of the findings, a third researcher, an expert in health-related stigma research (E.C.), participated in all analysis discussions (peer debriefing), and member checks were conducted on all transcripts (Creswell, 2014).

Findings

The following three major themes emerged from the study: the emasculating journey of a prostate cancer diagnosis, coping strategies for prostate cancer stigma, and system change required to address prostate cancer stigma.

The Emasculating Journey of a Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

Participants clearly articulated the negative effects of living in a society with masculine norms. Men consistently linked prostate cancer with a change to their perceived masculinity and self-image. They felt that prostate cancer changed societal perceptions of them as men, as well as their perceptions of themselves. They talked about how sexual dysfunction and incontinence challenged their sense of masculinity.

When diagnosed, many men felt that they could not talk about what they were going through. Words like “devastating,” “numbing,” and “it took the legs out from underneath me” were used to describe how they felt when they first learned of their diagnosis. One participant described it as follows:

Women talk about breast cancer. They talk to everyone. Some people hide it. You know, it’s just males, they don’t cry, they’re not supposed to cry, not supposed to do this, not supposed to do that, you know? Shit, we’re human.

Another participant suggested that many men do not talk about prostate cancer because of the known side effects:

Because it makes them feel inferior because they got [erectile dysfunction] or got a catheter in, they just don’t want to talk about it. Makes them feel inferior to the so-called normal man.

Participants expressed how much treatment and resulting side effects were not felt so much physically but emotionally. One participant expressed, “You don’t see our prostate, so you don’t miss it. But [others] might struggle emotionally because they feel their body is disfigured.” The internalization of a devalued body clearly weighed heavily on participants long after treatment. As another participant expressed, “The doctor said, ‘You’re 99% cured. I’m not worried about the 99%. I’m worried about the 1% you didn’t get.’ How bad is that going to be?”

Incontinence was also mentioned by participants as negatively affecting their daily lives. The participants expressed feelings of a loss of autonomy over their bodies and lives, because they had to ensure a bathroom was nearby or pads were available when needed. When talking about the inconvenience of incontinence, one participant explained, “That’s my life now. I’m tied to a pad.” Similarly, another participant stated, “Before I went to town, I always scouted the phone book to identify where all the restrooms were from here to my destination.”

The effects of internalized stigma—that prostate cancer makes men feel less masculine, particularly with regard to sex—was clearly articulated by all of the participants. As one participant described, it can even lead to life-ending thoughts: “I know some people, and they’ve been thinking about suicide. They can’t live up to expectations. If people expect you to perform a certain way and you don’t do it, you can’t do it.” Participants also spoke about how the internalized stigma around masculinity affected health-seeking behaviors. One participant recognized that some men may not get screened because of fear of a cancer diagnosis.

I think it’s a matter of the males always think of [side effects of prostate cancer], and this is why I think individuals have avoided being tested because they don’t want to be made less of a man. They know they’re going to have erectile dysfunction, but they don’t want to face that. They’re content to ignore the positive things because of the threat of erectile dysfunction.

Although a prostate cancer diagnosis was devastating to some participants and to others they knew, others tried to keep it in perspective and think about masculinity in a different way. One participant said, “The drive is there, but I’m not the fella I used to be, but the joy of [sex] is still there.” Another participant indicated that prostate cancer should not change the way men feel about themselves and that having sexual dysfunction does not affect his perception of his masculinity: “Whereas the sexual issues, that doesn’t bother me at all. I shot at 81 [at golf course]. That’s what I shoot. I’m not less masculine because I can’t get an erection now.”

Coping Strategies for Prostate Cancer Stigma

All of the participants spoke about different ways of coping with a prostate cancer diagnosis. The strategies they identified all strongly related to the emasculating journey of a prostate cancer diagnosis. Whereas some talked about using humor and avoidance, others talked about finally resigning to talking about their diagnosis, which was identified as a feminine strategy.

One of the most common coping mechanisms was humor. One participant said, “I find that humor is a great tool [when talking to others about having cancer]. It reduces the awkwardness.” Another participant said that humor helps to deal with an issue that cannot be changed. When asked about changing attitudes toward prostate cancer, he said the following:

Talk about it. See humor in it as opposed to, “You poor fella, you lost your prostate.” Keep hoping there’s a pill that you’re going to be able to get to regrow it [laughs] or a transplant.

Even after receiving a “50/50” prognosis, one participant made a joke to his physician about having a bone scan to check if he was “full of it.” Participants spoke about how jokes helped to alleviate the perceived awkwardness, begin the conversation with others, and ensure that one is not dwelling on the negatives of their disease.

Many of the participants also talked about avoidance and denial as strong coping mechanisms and spoke about how difficult it was to discuss their diagnosis with others. One participant said the following:

I didn’t tell anyone other than my wife. . . . It was a while before I told my son and daughter and their families. I didn’t see any point in having them worry unnecessarily about it, but then at the appropriate time, I decided they should know and we discussed it openly.

Although initially reluctant, one participant found that talking about his cancer diagnosis helped him to cope with his disease:

After I told my family, I started telling other people and especially friends, the male part of the family, indicating to them the importance of being tested, and how things went. Subsequent to that, I had quite a few phone calls from individuals who had found out that I had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and wanted to talk about it, and I felt that talking about it kind of helped me in that I felt that I was helping others.

Many men felt that sharing and offering support to others helped to alleviate the anxieties of others. One participant told the researchers about offering support to others: “I’ve been at a parts counter talking to this other buddy and this fella’s listening and says, ‘Can I have your name and number?’ and I said, ‘Yes b’y, call me anytime.’” Another participant expressed that talking is not initially a primary coping mechanism for many men (“with prostate cancer, men don’t talk about it as much”) but that once they do, it can have a dramatic effect. He said he often has people asking him to talk to a loved one: “Would you try to talk to them? They don’t seem to have anyone.”

This participant also spoke about how, in small communities, some men may not seek support, even though most people already know about their diagnosis:

There was a fella right down the road. He is being treated now and I was told, “So and so is being treated for the same thing that you had.” So, I called him and I said, “I heard you’re going in for the same thing I had. Well, you know if you want to talk, I’m available.” He just didn’t want to; he didn’t need to.

This participant posited that these small communities may also play a role in whether one discloses prostate cancer and side effects: “[People in rural communities] keep it all to themselves forever because it’s part of their sexual function and nobody talks about that in small areas of the province.”

Although there was a support group available to one participant, it “was not the type of support group that I was figuring on. There were older people there and . . . they sort of led me to believe that, OK, that part of your life is over.” Regardless, this participant felt it was important to raise awareness that “this is not an old man’s disease.” He said that others may “feel [prostate cancer] is a private thing, but to me, it’s just another disease, illness.”

System Change Required to Address Prostate Cancer Stigma

All of the participants talked about the challenge of navigating the healthcare system. Men were told to make their own decisions on their care, which provides autonomy, but it seemed they did not feel they had the capacity to make these decisions. Interviewees shared many stories about how their interactions with physicians affected their prostate cancer experience. One participant’s family physician told him, “I don’t do [digital rectal examination]. . . . I don’t believe in dealing with prostate cancer. I’m thinking you’ll die with it rather than die of it.” This participant was upset by this because, by not being offered a digital rectal examination, it “took the decision away from [me]. Regardless of what his thoughts are on it, it’s not his body. It’s my body.”

Following diagnosis, the participants said they would have liked more interaction with their oncologist. One participant expressed that he “would have liked some one-on-one with the doctor,” and even though he does not keep secrets, “some things are hard to express” when his wife is present. He would have liked some coaching or role-playing with the physician. In addition, there were times when his physician was teaching students, which created an additional barrier to communication: “You don’t want to sit around talking about how you can’t get your erection up and that kind of stuff with three or four students in the room.”

Not all experiences in this regard were negative. One participant felt as though the physician was attentive to him and the questions he had:

My urologist did give me some literature. . . . When I went back for my next visit, we chatted for a while and he answered any question I asked and didn’t hesitate about answering them. . . . He said he would go with surgery.

Some participants accepted that prostate cancer treatment may result in a lifetime of sexual dysfunction, but others wanted to do their best to avoid this outcome. One participant wanted assurance that his sexual function would not be affected. He told his surgeon, “Don’t tamper with my nerves,” and, to really ensure he got his point across, he told the surgeon the following:

If you cut me open and you realize that there’s a lot more cancer in there than I thought there was now both nerves have to be cut. Well, while I’m out for the count on the table and you got that scalpel in your hand, why don’t you just pull it across my throat.

Although he did not mean it literally, he felt the physician was not hearing him and did not understand how important sexual function was to him. His physician made statements such as, “Pick up your clubs and go play more golf,” or “Now, look, you’re 65, you’ve had your last 50 years of sex.” Because of these conversations, this participant changed physicians. His new physician ensured him they would do their best to maintain sexual function and if there was nerve damage, “We’ve got medication for that,” and explained the different sexual aids that exist.

Discussion

This study explored men’s experiences of prostate cancer and related stigma. Given the complex nature of stigma, the authors used a social–ecological perspective by examining the sources of stigma from multiple levels. Men experienced stigma on the intrapersonal (e.g., poorer self-concept because of changes in self-identity), interpersonal (e.g., avoiding disclosure because of discomfort), and institutional (e.g., lack of psychosocial support from their physician) domains of the social–ecological framework. In the interviews conducted, men most often reported experiencing stigma on the intrapersonal domain and discussed the effect stigmatization had on their masculine identity. As with other studies (Arrington, 2003; Parsons et al., 2009; Weber & Sherwill-Navarro, 2005), participants felt that sexual dysfunction and incontinence had a considerable effect on their self-concept and identity following treatment. To address their feelings of internal stigmatization, men identified coping strategies, such as humor, avoidance, and help seeking, to overcome negative emotions associated with prostate cancer. Men in this study also reflected on the role of the healthcare system, expressing feelings of lack of support and poor communication between themselves and their physician.

The most commonly discussed theme in this study was the journey through prostate cancer treatment and feelings of emasculation. These changes led to self-stigmatization because of changes in self-perception and identity. Often, men spoke about changes in sexual function and incontinence that could leave an individual feeling as “less of a man” or not living up to society’s expectations. A central tenet of masculinity is control and self-reliance (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Canham, 2009); therefore, loss of control of one’s body may threaten a man’s masculine identity, which may lead to stigma (Knapp et al., 2014).

Men identified sources of stigmatization but also identified a number of coping strategies. It was important for many of the participants to make jokes about cancer and see the humor in it. Humor is a common coping method that minimizes the psychological effect of cancer, helps individuals deal with difficult or embarrassing situations, makes them feel “normal,” and gives individuals control of how cancer makes them feel (Carver et al., 1993; Chapple et al., 2004). In relation to feelings of loss of control and masculinity, humor may have been a means of taking control of the emotional effect of cancer. In the current study, men seemed to use humor to show others they can be treated as normal and to alleviate any perceptions of discomfort among friends. The use of humor as a coping method among men with prostate cancer could be explored more closely in future research.

Interviewees felt that their family members, typically their spouse or partner, were their primary sources of interpersonal support. Social support has been found to be associated with improved coping, self-management, and health-related quality of life (Kershaw et al., 2008; Scholz et al., 2008) among men who have had prostate cancer. Unfortunately, some men who have had prostate cancer have identified that they have unmet support needs (Boberg et al., 2003; Lintz et al., 2003; Ream et al., 2008) and report feeling isolated and closed off following a diagnosis. These feelings can lead to poor self-evaluation and concept, which is associated with stigma. In addition, some respondents felt that available support groups did not offer the type of support they wanted. Some also felt that others in their community were reluctant to talk about cancer, which is not an uncommon finding among cancer-related stigma literature.

Many men in the current study reported feeling a lack of support from their healthcare providers. For example, participants reported that they were provided with information on their condition and their treatment options and then were asked to decide on a course of treatment. Some men would have liked more time to speak with their physician about their diagnosis and treatment. Many components of a cancer diagnosis can lead to stigmatization. Cancer is associated with death, which can make individuals fearful of the disease (Knapp et al., 2014). This fear can lead to avoidance and poor coping. Healthcare providers, such as physicians and nurses, have the opportunity to explain the diagnosis to their patients and discuss treatment and side effects. Physicians may not focus on the everyday symptoms a patient may experience (Rosman, 2004). As a result, the physician may not understand the psychological implications of the side effects of cancer treatment. There is a need for improved communication between patients and their provider throughout the entire cancer continuum (Knapp et al., 2014). Oncology nurses can play a key role in communication with patients and can function as professional cancer navigators, helping patients to understand and navigate the healthcare system and connecting patients to supports within their community (Cummings et al., 2018). Oncology nurses have the education to offer psychosocial support to their patients and to identify signs of distress (Estes & Karten, 2014). This is particularly important considering that physicians may not have the skills or may be too busy to provide required psychosocial support (Estes & Karten, 2014). Although oncology nurses are specially trained to deliver these types of complex care, they are often not supported within the healthcare system to fulfill this role (Lemonde & Payman, 2015). Resources need to be allocated (e.g., improved patient–nurse ratio) and roles clearly defined to support oncology nurses within healthcare teams. An increased role for oncology nurses may improve the experience of patients within the healthcare system and has the potential to reduce stigmatization through improved psychosocial support.

Men in the current study frequently spoke about the decision-making approach employed by their healthcare providers. Interviewees most often felt that their provider was taking a paternalistic approach, deciding that they knew what was best for the patient, or taking an informed decision-making approach, where the provider gives patients details of their treatment decision and asks patients to make the decision (Charles et al., 1997). These types of decision-making processes are not considered to be best practices. Instead, a shared decision-making approach should be employed by providers to ensure that patients are sure of their decisions and feel supported (Charles et al., 1997). Shared decision making can occur between patients and their provider, where the provider lays out treatment options, along with corresponding benefits and risks, and the patients share their values and preferences (Charles et al., 1997). Through a shared decision-making process, the patient is an active recipient of care, and the treatment decision is made and agreed on by both parties (i.e., the patient and provider). Improved support and involvement in the decision-making process may increase patients’ feelings of control and their self-concept, thereby reducing experiences of stigma. Providers may need additional training to ensure that their patients are active members of the care team and best practice decision-making processes are used.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that all participants had some form of active treatment. As a result, findings may not be generalizable to other treatment types, such as active surveillance. Participants all resided in the province of NL; therefore, experiences of interviewees may not be generalizable to other provinces or countries.

Implications for Nursing

Men in this study identified prostate cancer as an emasculating journey, experiencing changes in their self-concept and identity. They identified coping strategies, such as humor and avoidance, but also reported a lack of support from their physicians. Nurses can fill this gap in the treatment of prostate cancer and mitigate the effect of stigma on men with prostate cancer. Nurses, particularly oncology nurses, have the necessary training to provide psychosocial support and counseling to patients experiencing stigma. Men in this study also felt that their physicians did not give them enough time to discuss their condition and treatment decisions. Oncology nurses can help to improve the communication between patients and their providers by providing education to individuals with cancer about their treatment options, allowing them to have informed conversations with members of their healthcare team and take part in decision making. Interviewees also reported feeling the need for additional support from their healthcare team. Nurse navigators are able to offer informational and emotional support to individuals with cancer throughout their healthcare journey, improving their experience of care and care coordination (Thera et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2014). The addition of nurses to oncology teams has the potential to reduce the effect that stigma has on men with prostate cancer through improved support and patient navigation.

Conclusion

Findings from this study suggest that men who have had prostate cancer experience it as an emasculating journey resulting in feelings of stigmatization. Men identified various coping strategies, such as humor and avoidance, but reported a lack of support from within the healthcare system. Oncology nurses could improve the experience of men with prostate cancer within the healthcare system through improved psychosocial support and the identification and treatment of prostate cancer stigma. Research should examine the role of oncology nursing across the cancer care continuum to determine the effect these providers can have on stigmatization and related psychosocial outcomes among individuals with cancer.

About the Author(s)

Richard Buote, BSc, MSc, is a PhD candidate in the Division of Community Health and Humanities at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada; Erin Cameron, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Human Sciences Division at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada; and Ryan Collins, BA, MSc, is a graduate student and PsyD candidate in the Department of Psychology, and Erin McGowan, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Human Kinetics and Recreation, both at Memorial University of Newfoundland. This research was funded by Memorial University’s Seed, Bridge, and Multidisciplinary Fund. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design and the manuscript preparation. Buote and Cameron completed the data collection. All authors contributed to the analysis. McGowan can be reached at emcgowan@mun.ca, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted September 2019. Accepted February 20, 2020.)