Preparing Oncology Advanced Practice RNs as Generalists in Palliative Care

Objectives: To train and support oncology advanced practice RNs (APRNs) to become generalist providers of palliative care.

Sample & Setting: APRNs with master’s or doctor of nursing practice degrees and at least five years of experience in oncology (N = 165) attended a National Cancer Institute–funded national training course and participated in ongoing support and education.

Methods & Variables: Course participants completed a precourse, postcourse, and six-month follow-up evaluation regarding palliative care practices in their settings, course evaluation, and their perceived effectiveness in applying course content in their practice.

Results: The precourse results showed deficiencies in current practice, with a low percentage of patients having palliative care as part of their oncology care. Barriers included lack of triggers that could assist in identifying patients who could benefit from palliative care. Six-month postcourse data showed more APRNs participating in family meetings, recommending palliative care consultations, speaking with family members regarding bereavement services, and preparing clinical staff for impending patient deaths.

Implications for Nursing: APRNs require palliative care training to integrate this care within their role. APRNs can influence practice change and improve care for patients in their settings.

Jump to a section

Palliative care has become increasingly recognized as an important aspect of quality cancer care addressing critical aspects of quality of life (Buller et al., 2019; Dalgaard et al., 2014; Dumanovsky et al., 2016; Ferrell & Paice, 2019; Greer et al., 2013; Hui et al., 2015; Kelley & Morrison, 2015; Siler et al., 2018). As the field of palliative care has developed, consensus has also been growing regarding the need to integrate this care from the time of cancer diagnosis (Partridge et al., 2014). In 2018, the National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care published the fourth edition of national palliative care guidelines, further emphasizing the need to integrate palliative care in all serious illness care. A key emphasis of these guidelines is the need to integrate palliative care within the role of all clinicians, including oncology nurses and physicians, who provide care to patients who are seriously ill to meet the demands that far exceed the workforce of palliative care specialists.

The body of evidence has been growing regarding the benefits of palliative care across domains of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being of patients and families (Bakitas et al., 2015; Berglund et al., 2015; Ferrell et al., 2015; McCorkle et al., 2015; Van Lancker et al., 2014). Benefits of palliative care have also been demonstrated for healthcare systems in terms of reduced hospitalizations and intensive care unit stays, increased completion of advance directives, and reduced futile care at the end of life (Henson et al., 2015; May et al., 2014, 2015; Partridge et al., 2014).

Substantial discussion has taken place regarding workforce issues related to the delivery of palliative care, including the need for increased education to prepare nurses to provide this care (Aldridge et al., 2016; Kamal et al., 2016; Pang et al., 2015; Quill & Abernethy, 2013). Oncology clinicians require training to incorporate palliative care within their practice (End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium [ELNEC], 2019), and nurses are a key component of the oncology workforce recommended to deliver improved palliative care (Dahlin et al., 2016, 2017).

This project was intended to prepare oncology advanced practice RNs (APRNs) for an expanded role by incorporating palliative care within their practice. Supporting APRNs to serve as generalist palliative care providers has been recommended by numerous sources (Aldridge et al., 2016; Dahlin et al., 2016, 2017; ELNEC, 2019; Kamal et al., 2016).

Methods

The purpose of this education project was to train and support oncology APRNs to become primary palliative care clinicians. In addition, the project aimed to promote leadership and mentorship as these APRNs expanded their roles and became models for other APRNs. These goals were achieved through the creation of a curriculum specific to the oncology APRN population, building on the extensive previous educational programs by the investigators through ELNEC. The ELNEC project training programs have been conducted nationally and internationally. This training program was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Sample and Setting

Criteria for participation in the training course included the following:

• APRNs with at least five years of oncology nursing experience

• Nurses in adult and pediatric care settings

• Master’s or doctor of nursing practice degree

• Commitment to spend time with the palliative care team within their institution (40 hours over 12 months; this was intended to foster collaboration by the APRN with the specialty palliative care service.)

• Agreement to attend one webinar meeting monthly for 12 months to provide ongoing education and support

• Mandatory follow-up evaluations at 6 and 12 months postcourse

APRNs were encouraged to come as teams with a colleague within their organization for ongoing support.

Methods

Training Course

A skills-based innovative curriculum was designed for oncology APRNs to be trained through five national workshops to be conducted from 2018 to 2022. The courses include a maximum of 100 APRNs per course, or 500 nurses over five years, which was the limit of the funding provided by the NCI. Participants receive free course registration and a travel stipend. Applicants complete an initial survey and provide letters of support from their cancer program and the palliative care program. Individual learning goals are submitted with the application and evaluated at 6 and 12 months postcourse for achievement. The course is open to APRNs in pediatric and adult oncology, with separate breakout sessions for each group. Courses 1 and 2 were completed in April and November 2018, respectively. The course application informs participants that pre- and postcourse evaluation is required.

Course Agenda

The conceptual framework for the curricula was the NCP for Quality Palliative Care (2018) guidelines, and the course is organized according to the eight NCP palliative care domains. The NCP framework also guides the evaluation process. The first day covers the domain of structure and processes of care and emphasizes building palliative care practices into routine oncology care. Content specific to pain management is under Domain 2 on physical, social, and spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care. The didactic content is followed by small group work applying the content to practice through case studies. The day ends with breakout sessions in which participants choose from topics for additional focus.

Day 2 covers the domains of cultural aspects of care, symptom management, psychological and psychiatric aspects of care, and case study discussion. An additional laboratory session addresses communication and topics of advance care planning and goals-of-care discussions as clinical examples in which APRNs are often involved.

Day 3 covers the final domain of care as patients near the end of life. The remainder of the day is intended to focus on goal development so that participants are prepared to return to their work settings and implement their goals. Time is also provided for sharing their plans because participants learn a great deal from their colleagues. The course ends with a celebration of completion and a “blessing of the hands” ritual.

Teaching methods for the course are designed to provide experiential learning through the use of eight different laboratory or breakout sessions during the program, including role play, small group discussion, and time for the APRNs to develop goals for implementing the education in their daily practice. The lecture sessions also include diverse teaching strategies, such as video scenarios demonstrating APRNs performing the skills identified in the curriculum, including assessing and counseling patients, offering psychosocial support, leading family meetings, and demonstrating communication skills.

Results

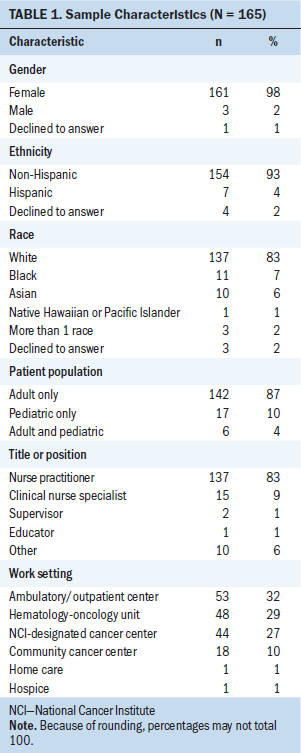

All data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Table 1 presents the demographic data of the participants from the first two courses. The participants represented 40 states.

Status of Palliative Care

Participants reported that their patient populations who most frequently received palliative care included those with pancreatic, lung, colon, and breast cancers. The majority of participants (n = 92, 56%) reported that 20% or less of their patients are referred for palliative care, but a positive finding was that the majority of APRNs (n = 136, 82%) could request a palliative care consultation. However, most participants (n = 123, 75%) also reported that they did not have triggers used in their system to identify patients who would benefit from a palliative care consultation.

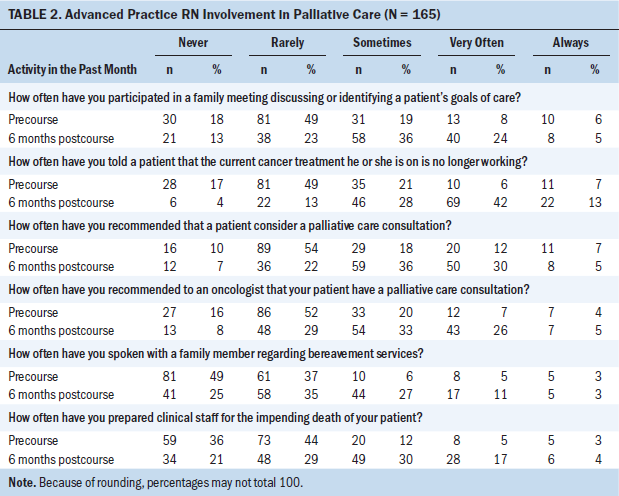

Table 2 presents baseline data completed prior to the course and follow-up data six months later regarding the APRN’s role in various palliative care activities. The nurses reported overall limited involvement in areas such as participating in family meetings, recommending palliative care to oncologists or patients, speaking with families about bereavement services, or preparing clinical staff for the death of a patient. Each of these activities was selected, based on the national palliative care guidelines, as important aspects of care across domains (NCP for Quality Palliative Care, 2018). Activity increased in these areas at six-month follow-up.

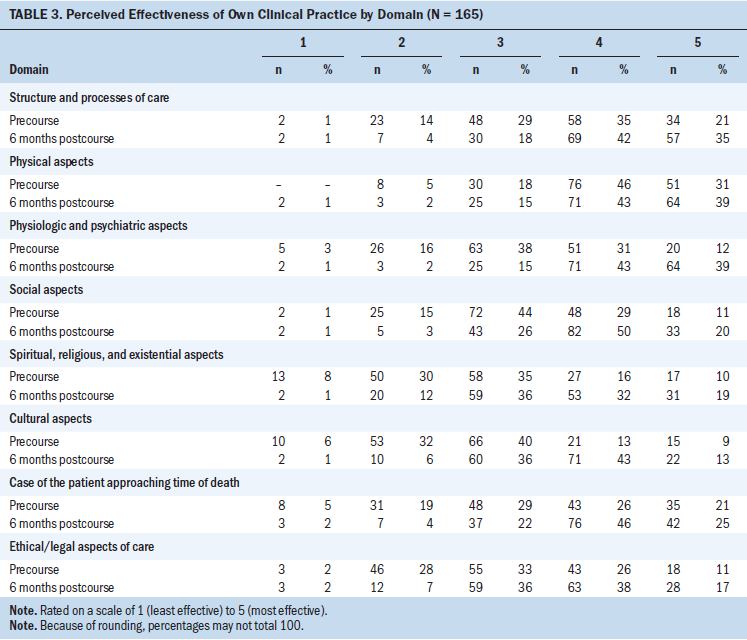

Table 3 describes the participants’ perceived effectiveness of their own clinical practice according to each of the NCP domains for quality palliative care. These data demonstrate the opportunities for APRNs to influence all aspects of quality patient care, including processes of care and physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions.

Course Evaluation Data

On a scale of 0 (lowest rating) to 5 (highest rating), each session was highly rated by participants. The overall course received a rating of 4.92 regarding the applicability of the course to practice.

Discussion

The vast majority of course participants found the APRN oncology training to be useful for their practice and the course information to be stimulating and thought-provoking regarding palliative care issues that arise in their practices. The data also reveal important areas for continued quality improvement. For example, the responses indicate that only 20% of the participants’ patients have palliative care as part of their care, but that the participants are able to independently request palliative care consultations for their patients with cancer. By training the oncology APRNs in palliative care, the course helped equip participants with the knowledge to return to their practices and conduct family meetings, recommend palliative care consultations, communicate with patients and family members about goals of care, communicate with oncologists about palliative care consultations, speak with family members about bereavement services, and prepare clinical staff for a patient’s impending death. More work needs to be done, including having more APRNs trained in palliative care and doing more research to evaluate outcomes and test models to see how best to ensure that the growing number of patients with cancer in the United States receive palliative care by nurses skilled in providing such care.

Implications for Nursing

APRNs will continue to play a vital role in the provision of palliative care for patients across the cancer trajectory. This training program has demonstrated the interest and benefits of palliative care training for APRNs in oncology. Many challenges exist in enhancing palliative care within the role of APRNs who are already busy in their clinical roles managing complex patients. However, the participants thus far have reported their ability to enhance their own knowledge and skills to incorporate this education into practice. The monthly webinar calls provide opportunities for networking and for the APRNs to discuss how to integrate palliative care within the significant demands of their practice.

This educational program has important implications as the healthcare system responds to a growing population of individuals with cancer who require palliative care to manage symptoms and quality-of-life concerns. Three additional national courses will be held from 2019 to 2022, and the project has also increased the financial support for underrepresented minority nurses to attend to promote greater diversity.

Conclusion

Individuals with cancer and their families benefit from palliative care to address quality-of-life concerns from the time of diagnosis through treatment, survivorship, recurrence, and the end of life. Nurses at all levels of oncology practice can integrate palliative care within their roles and settings to ensure that this aspect of quality cancer care is consistently provided. APRNs collaborating with their RN colleagues and all members of the interprofessional team can improve processes of care to promote patient quality of life.

About the Author(s)

Betty Ferrell, RN, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN®, CHPN®, is a professor and the director of the Division of Nursing Research and Education at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, CA; Pamela Malloy, MN, RN, FPCN®, FAAN, is the director and a co-investigator of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) project at the American Association of Colleges of Nursing in Washington, DC; Rose Virani, RNC, BSN, MHA, FPCN®, is a senior research specialist and a director of the ELNEC project, and Denice Economou, PhD, CNS, CHPN®, is a senior research specialist, both in the Division of Nursing Research and Education at City of Hope National Medical Center; and Polly Mazanec, PhD, AOCN®, ACHPN®, FPCN®, FAAN, is a research associate professor in the School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH. No financial relationships to disclose. Ferrell, Malloy, and Mazanec contributed to the conceptualization and design. Ferrell, Virani, Economou, and Mazanec completed the data collection. Ferrell and Economou provided statistical support. Ferrell, Malloy, Virani, and Economou provided the analysis and contributed to manuscript preparation. Ferrell can be reached at bferrell@coh.org, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2019. Accepted October 17, 2019.)

References

Aldridge, M.D., Hasselaar, J., Garralda, E., van der Eerden, M., Stevenson, D., McKendrick, K., . . . Meier, D. (2016). Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: A literature review. Palliative Medicine, 30(3), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315606645

Bakitas, M.A., Tosteson, T.D., Li, Z., Lyons, K.D., Hull, J.G., Li, Z., . . . Ahles, T.A. (2015). Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(13), 1438–1445. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362

Berglund, C.B., Gustafsson, E., Johansson, H., & Bergenmar, M. (2015). Nurse-led outpatient clinics in oncology care—Patient satisfaction, information and continuity of care. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(6), 724–730. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.05.007

Buller, H., Virani, R., Malloy, P., & Paice, J. (2019). End-of-life nursing and education consortium communication curriculum for nurses. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 21(2), E5–E12. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000540

Dahlin, C., Coyne, P., & Ferrell, B. (Eds.). (2016). Advanced practice palliative nursing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190204747.001.0001

Dahlin, C.M., Coyne, P.J., Paice, J., Malloy, P., Thaxton, C.A., & Haskamp, A. (2017). ELNEC-APRN: Meeting the needs of advanced practice nurses through education. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 19(3), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000340

Dalgaard, K.M., Bergenholtz, H., Nielsen, M.E., & Timm, H. (2014). Early integration of palliative care in hospitals: A systematic review on methods, barriers, and outcome. Palliative and Supportive Care, 12(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/s1478951513001338

Dumanovsky, T., Augustin, R., Rogers, M., Lettang, K., Meier, D.E., & Morrison, R.S. (2016). The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: A status report. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 19(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0351

End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium. (2019). About ELNEC. https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/About

Ferrell, B., Sun, V., Hurria, A., Cristea, M., Raz, D.J., Kim, J.Y., . . . Koczywas, M. (2015). Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 50(6), 758–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.005

Ferrell, B.R., & Paice, J.A. (Eds.). (2019). Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190862374.001.0001

Greer, J.A., Jackson, V.A., Meier, D.E., & Temel, J.S. (2013). Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 63(5), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21192

Henson, L., Gao, W., Higginson, I., Smith, M., Davies, J.M., Ellis-Smith, C., & Daveson, B.A. (2015). Emergency department attendance by patients with cancer in the last month of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 385(S1), S41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60356-7

Hui, D., Kim, Y.J., Park, J.C., Zhang, Y., Strasser, F., Cherny, N., . . . Bruera, E. (2015). Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. Oncologist, 20(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0312

Kamal, A.H., Bull, J., Wolf, S., Samsa, G.P., Swetz, K.M., Myers, E.R., . . . Abernethy, A.P. (2016). Characterizing the hospice and palliative care workforce in the U.S.: Clinician demographics and professional responsibilities. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(3), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.016

Kelley, A.S., & Morrison, R.S. (2015). Palliative care for the seriously ill. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(8), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1404684

May, P., Garrido, M.M., Cassel, J.B., Kelley, A.S., Meier, D.E., Normand, C., . . . Morrison, R.S. (2015). Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: Earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(25), 2745–2752. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2014.60.2334

May, P., Normand, C., & Morrison, R.S. (2014). Economic impact of hospital inpatient palliative care consultation: Review of current evidence and directions for future research. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(9), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0594

McCorkle, R., Jeon, S., Ercolano, E., Lazenby, M., Reid, A., Davies, M., . . . Gettinger, S. (2015) An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(11), 962–969. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0113

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (4th ed.). National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-N…

Pang, G.S.Y., Qu, L.M., Wong, Y.Y., Tan, Y.Y., Poulouse, J., & Neo, P.S.H. (2015). A quantitative framework classifying the palliative care workforce into specialist and generalist components. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(12), 1063–1069. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0017

Partridge, A.H., Seah, D.S.E., King, T., Leighl, N.B., Hauke, R., Wollins, D.S., & Von Roenn, J.H. (2014). Developing a service model that integrates palliative care throughout cancer care: The time is now. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(29), 3330–3336. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.54.8149

Quill, T.E., & Abernethy, A.P. (2013). Generalist plus specialist palliative care—Creating a more sustainable model. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(13), 1173–1175. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1215620

Siler, S., Mamier, I., & Winslow, B. (2018). The perceived facilitators and challenges of translating a lung cancer palliative care intervention into community-based settings. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 20(4), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000470

Van Lancker, A., Velghe, A., Van Hecke, A., Verbrugghe, M., Van Den Noortgate, N., Grypdonck, M., . . . Beeckman, D. (2014). Prevalence of symptoms in older cancer patients receiving palliative care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 47(1), 90–104.