The THRIVE© Program: Building Oncology Nurse Resilience Through Self-Care Strategies

Objectives: To develop an evidence-based program for addressing the concerns of burnout and secondary trauma and building on the concept of resilience in oncology healthcare providers.

Sample & Setting: 164 oncology staff, of which 160 were nurses, at the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute in Columbus, Ohio.

Methods & Variables: Oncology nurses and other providers participated in the THRIVE© program, which consists of an eight-hour retreat designed to teach self-care strategies, a six-week private group study interaction on a social media platform, and a two-hour wrap-up session. The Compassion Fatigue Short Scale and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale were used to evaluate the program.

Results: In self-assessments prior to THRIVE, nurse managers demonstrated the greatest degree of burnout, and bedside/chairside nurses demonstrated the greatest degree of secondary trauma. The greatest improvement in average scores from pre- to postprogram assessment was in increased resilience and decreased burnout. Increased resilience scores were sustained for a six-month period after THRIVE participation.

Implications for Nursing: Oncology healthcare providers must identify self-care strategies that build their resilience for long, successful careers.

Jump to a section

Healthcare providers (HCPs), particularly nurses and other professional caregivers in the oncology setting, experience profound effects on their professional and personal lives from the ongoing daily exposure to human trauma. In the dynamic healthcare environment, it is important for oncology HCPs to self-monitor their professional quality of life. They must learn to identify experiences that potentially cause burnout and secondary trauma and then develop ways to counteract these experiences.

Evidence of the suffering of HCPs is demonstrated in many representative reports. The equivalent of one physician per day commits suicide in the United States, the highest of any profession (Kane, 2019). According to the American Nurses Association (2017), 68% of nurses reported putting their patient’s safety and well-being ahead of their own, 50% reported having been bullied in the workplace, 25% reported having been physically assaulted at work by a patient or a patient’s family member, and 9% reported being afraid for their own physical safety while at work. Perhaps most disturbing is the fact that 5,200 deaths per year occur in the United States from preventable medical errors, and in roughly 108,000 deaths per year, a medical error is a contributory factor (Gorski, 2019). These statistics speak to the difficulties HCPs face in the current environment.

The purpose of this quality improvement educational intervention is to develop an evidence-based program for addressing the concerns of burnout and secondary trauma and building on the concept of resilience in oncology HCPs.

Literature Review

Burnout has been defined as a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion resulting in high levels of depersonalization and low levels of personal satisfaction in one’s work (Dyrbye et al., 2017). The environment that nurses and other HCPs work in can drive burnout. Burnout can lead to depression and unnecessary suffering. Kelly and Lefton’s (2017) study found burnout to be predicted by an increase in job stress and a decrease in job satisfaction and enjoyment. The prevalence of burnout is concerning because it can affect quality, safety, and the performance of the healthcare system (Dyrbye et al., 2017).

Secondary Trauma

When a patient’s traumatic event begins to traumatize the HCP, it is known as secondary trauma or vicarious trauma. This kind of trauma can occur when nurses and other HCPs put aside their own personal and psychological needs to meet the needs of their patients. Kelly and Lefton (2017) found that stress was decreased when nurses felt more satisfaction and enjoyment in their job, so secondary trauma can be mitigated.

Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue can be defined as a lack of balance between compassion satisfaction and professional quality of life, as well as feelings of hopelessness (Sullivan et al., 2019). HCPs experiencing compassion fatigue may exhibit symptoms such as fatigue and irritability, dread of going to work or walking into a patient’s room, lack of joy in life outside of work, overindulgence in alcohol or food, or aggravation of existing physical ailments. They may reexperience traumatic clinical events and have intrusive thoughts or sleep disturbances (Najjar, Davis, Beck-Coon, & Doebbeling, 2009; Reimer, 2014). Significant work-related stress in nurses and other HCPs is a direct result of caring for patients with a disease such as cancer, which has high morbidity and mortality, many deleterious side effects, long-term treatment, and personal and emotional hardships for patients (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Fetter, 2012; Henry, 2014; Reimer, 2014). Profound physical and emotional fatigue has been documented in nurses who care for patients with cancer, resulting in damaged relationships and an increased desire to leave the field (Kelly, Runge, & Spencer, 2015; Perry, Toffner, Merrick, & Dalton, 2011). Compassion fatigue can also have a negative effect on patient outcomes (Kelly & Lefton, 2017). Some common potential nurse stressors include grief and loss, moral and ethical dilemmas, and the influence of clinical trials (Grafton, Gillespie, & Henderson, 2010; Zander, Hutton, & King, 2010). Not only do staff suffer, but hospitals also bear the financial and non-monetary cost of a burdened workforce. Maintaining a robust nursing staff is essential in the current high-tech, high-acuity healthcare field (Tarantino, Earley, Audia, D’Adamo, & Berman, 2013).

Compassion Satisfaction

Compassion satisfaction can be defined as the pleasure a nurse or HCP gets from doing his or her work, and is often connected to the meaning derived from one’s work (Kelly et al., 2015). Compassion satisfaction has a positive influence on the nurse (Kelly & Lefton, 2017). The concept of being a witness to the suffering of others requires that the person witnessing the pain must also witness and attend to their own personal suffering (Corso, 2012; Grafton et al., 2010). Oncology HCPs must be able to find meaning in what they do. The ability to do so is affected by their day-to-day clinical experiences and their practice environment. Self-awareness, health promotion, and activities that foster renewal can promote compassion satisfaction (Kelly et al., 2015). The data from a study by Denigris, Fisher, Maley, and Nolan (2016) indicate a major source of risk for compassion fatigue within the social context of the nursing environment, and both institutional and interpersonal aspects are included. Kelly and Lefton (2017) support the hypothesis that a nurse’s satisfaction with his or her work can be a key predictor of the level of compassion satisfaction. The need to focus on self-care and compassion satisfaction may be even more essential with younger nurses and HCPs. Kelly et al. (2015) found that younger nurses—the millennial generation, aged 21–33 years—may be at more risk of experiencing higher burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress and less compassion satisfaction than their older colleagues.

Resilience

Resilience has been described as one of the factors that can help mediate stress in the oncology setting. It can be described as the ability to overcome negative situations through effective coping and adaptation when faced with adversity (Cleary, Kornhaber, Thapa, West, & Visentin, 2018; Zander et al., 2010). Resilience is not only the ability to persevere through hardships, but also to actually undergo personal change that allows for personal growth. It involves the ability to adapt to the stressful situation regardless of adversity. Oncology nurses and other HCPs need to develop resilience to positively overcome obstacles that the workplace may impose on them (Grafton et al., 2010).

Support for oncology nurses and other HCPs is often not formalized. Frequently, nurses are taught that self-care and stress reduction can help to ease the burden of compassion fatigue, but specific measures and self-care strategies are not taught. Strategies may not be applied because of lack of practice or support. Personal resilience strategies, taught and then employed effectively, may improve the management or possibly prevent extreme consequences of burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious trauma (Fetter, 2012; Henry, 2014). Although oncology nurses report potential for great reward and job satisfaction, studies reveal that high levels of oncology nurse depersonalization and exhaustion may leave them feeling a lack of organizational support (Aycock & Boyle, 2009; Reimer, 2014).

Methods

Relationship-based care (RBC) is the theoretical framework that supports the professional practice model for nursing at the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (The James) in Columbus, Ohio. RBC is an evidence-based model that helps to create a healing environment in healthcare organizations (Koloroutis, 2004). The three key components in RBC are relationships with patients and their family members, relationships with colleagues, and relationship with self. Building on the crucial relationship with self, relationship-based self-care requires knowing oneself and personal drivers of contentment and satisfaction well enough that one is able to select effective self-care strategies to increase resilience when consistently employed. Self-knowing is critical for healthy work relationships and the capacity for empathy. Without this, a nurse or other HCP’s emotional reaction may adversely affect his or her capacity for optimal work. Effective self-care requires that the individual possesses the skills and knowledge to manage his or her own stress, articulate personal needs and values, and balance the demands of the job with physical and emotional health and well-being. The relationship with self is fundamental to maintaining optimal health, demonstrating empathy, and being productive (Koloroutis, 2004).

Sample and Setting

The sample consists of 164 oncology staff, of which 160 were RNs or advance practice RNs at The James. In addition, nine THRIVE© program facilitators completed the preprogram assessment as a baseline measure of their competence in the role of supporting this program. Table 1 shows the distribution of the various staff roles who have attended the program to date.

THRIVE Program

The THRIVE program was developed after an extensive literature review by two clinical nurse specialists, one with certification in psychiatry and mental health. A protocol document was originally submitted to the institutional review board at The James, and the program was determined to be an educational intervention to increase quality of work for nurses. A flyer was distributed to individuals and groups who were considered to be likely participants, and staff could voluntarily register.

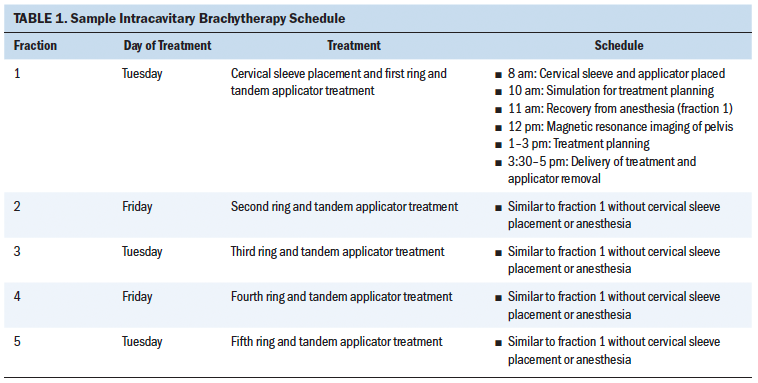

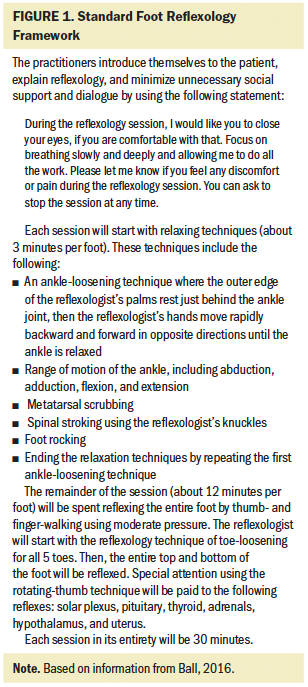

Staff participated in the THRIVE program, which includes an eight-hour retreat designed to teach self-care strategies, followed by a six-week private group study on a social media platform, and a final two-hour wrap-up session. The retreat included sessions such as mindfulness, art, journaling, guided imagery, and acupressure. The full retreat schedule is presented in Figure 1. The goal of the retreat is for participants to engage in a variety of self-care experiences. The intention is that at least one self-care activity will resonate with the individual and be integrated into routine self-care. The retreat contains minimal didactic content and is almost exclusively focused on active experiential exercises and supportive discussion.

Retreat Sessions

Spirituality: For many, the term spirituality is synonymous with religious beliefs and practices; for others, it is one’s relationship with the natural world. Spirituality has also been described as the search to understand the meaning of existence and the purpose of life and death (Burkhardt & Nagai-Jacobson, 2015). In the broadest terms, spirituality can be defined as one’s belief in a connection to something greater than oneself. According to Burkhardt and Nagai-Jacobson (2015), “Spirituality is the essence of our being which permeates our living in relationship, infuses our unfolding awareness of who and what we are, our purpose in being, and our inner resources, and shapes our life journey” (p. 6).

During the THRIVE retreat, the content is reviewed with participants and then applied in a small group circle discussion. The circle provides a space where all are given a chance to speak and be supported. The discussion centers around the relational nature of the art and the science of nursing. Patients look to nurses not only to provide technically competent skills, but also to be fully present to them as whole human beings—mind, body, and spirit. Participants share specific examples of this application in their personal lives.

Mindfulness: Mindfulness is another tool that can be used to reduce stress and burnout in nurses and other HCPs. Mindfulness is described by Orellana-Rios (2017) as consciously bringing awareness to the here-and-now experience with openness, receptiveness, and interest. Mindfulness practice is opposite in purpose to the usual nurse mindset and pride in multitasking. Mindful practices combine intuition, concentration, and the induction of the relaxation response (Caley et al., 2017). These aspects of mindful practice form the foundation for many relaxation activities; therefore, mindfulness is at the center of the majority of the THRIVE retreat’s activities.

In addition, the program explores the concepts of consciousness, awareness, presence, and openness with a mindful eating exercise. Each participant receives a small item of food and is instructed to use his or her five senses to savor the item. The activity illustrates mindful awareness of a mundane activity. The activity can increase the participant’s appreciation for the day-to-day activities, but also highlights patterns of behavior. The eating exercise can signal awareness of parts of oneself that are usually ignored, particularly for nurses and HCPs. Lastly, it introduces a greater awareness of one’s environment and the effect that it has on the individual.

Art therapy: Art therapy can be an effective method for promoting resilience in clinical staff through the use of exercises that promote identification of positive strengths and coping skills. Research demonstrates that focusing on positive emotions, such as joy, can promote a more positive outlook and enhance a sense of well-being (Wilkinson & Chilton, 2013). An art therapy technique in a group setting with subsequent group processing can assist nurses and other HCPs to identify and verbalize priorities and strengths, therefore empowering them to take better care of themselves on a daily basis.

During the THRIVE retreat, participants are provided with a variety of art materials, including stationery, fabric squares and scraps, ribbon, yarn, threads, beads, and trinkets, and instructed on how to create a spirit doll. First, participants record, on the provided stationery, several things that bring them joy. The stationery is then crumpled up to form the head of the doll. Then, participants create, dress, and accessorize their doll. Many participants are uncomfortable with their creativity at the start of the exercise, but often develop a sense of flow and a sense of play, both of which can enhance the sense of well-being (Feen-Calligan, McIntyre, & Sands-Goldstein, 2009).

The process allows each doll to be unique to the participant, varying widely in shape, color, and theme. Spirit dolls range from nurses to princesses, warriors, dancers, spiritual leaders, and more. Participants take pride in sharing how their dolls represent various aspects of themselves, their dreams and goals, and their priorities. At times, there is laughter or tears as participants share personal stories and insight they gained as a result of creating their dolls. In addition, there is a sense of community, camaraderie, and emotional support as the participants interact with one another in the group setting.

Aromatherapy: Aromatherapy is the science and practice of using essential oils extracted from the roots, bark, stems, flowers, and leaves of plants to promote physical, mental, and emotional health and well-being. Plant-based oils served as humankind’s first medicine, going back at least 4,000 years (Lua & Zakaria, 2012). Aromatherapy was first implemented in healthcare facilities in the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the late 1990s, aromatherapy became recognized by state boards of nursing throughout the United States as a legitimate part of holistic nursing (Lane et al., 2012). Aromatherapy quickly became the most popular and fastest growing of all complementary therapies among American nurses for enhancing care (Lee & Hwang, 2011).

Essential oils can be used in a variety of ways, such as diffusion into the air, direct inhalation, oral consumption, or via a topical or transdermal route. Nurses administer aromatherapy to patients through use of a diffuser or direct inhalation to improve insomnia, fatigue, somnolence, nausea, dyspnea, anxiety, depression, anorexia, and pain. Because of its uplifting qualities, the use of aromatherapy has widely been adopted by nurses to mitigate the effects of stress and fatigue and support self-care by enhancing mental and emotional balance and well-being, diminishing anxiety and fatigue, and boosting energy. THRIVE participants receive aromatherapy bracelets and were assisted with dosing an appropriately selected essential oil or blended scent.

Guided imagery: Guided imagery is a mind–body approach that focuses attention on visual, audible, or other sensory images for therapeutic purposes (Rao & Kemper, 2017). The term “imagery” may be misleading because the process of meditative guided imagery practice involves the whole body, the emotions, and all of the senses. This is an important distinction because many people find visualization difficult. Significant research has been conducted on the effects of guided imagery since the 1980s, and studies have found this meditative process to be a highly effective tool in positively influencing overall health, performance, and creativity (Patricolo et al., 2017). Researchers and practitioners find that even 10 minutes of imagery can help manage pain, improve immune cell activity, lower blood pressure and heart rate, lower glucose and cholesterol levels, and even decrease blood loss during surgery (Patricolo et al., 2017).

Guided imagery meditation has become a tool often used by nurses to help alleviate their distress, reduce anxiety, promote sleep, and provide a sense of mastery and confidence in their nursing care. During the THRIVE retreat, nurses are led through guided imagery relating to their transition away from work after a busy shift. They visualize giving a report to the oncoming nurse and handing over their pager or phone—actually feeling the weight of those tools leaving their hand. They pack up the issues of the shift in a backpack, such as the difficult discussion with a physician, the unhappy family member, and the patient whose pain was not optimally controlled. As they leave the doors of the hospital, they decide to leave their backpack by the entrance, feeling the weight off their shoulders. They realize that the issues contained inside will be taken care of by their colleagues and they can pick the backpack up again upon their return.

Independent Study

At the conclusion of the retreat, the participants are invited to join a private social media group with restricted viewing access and available only to other group members and program facilitators. During the ensuing six weeks, facilitators challenge group members with three exercises per week focused on applying and furthering what they learned during the retreat. These exercises can be completed in an average of 10 minutes or less per day by posting comments or pictures on the group’s social media platform. This ongoing group independent study allows for practice of the newly learned skills in everyday work and home life, and it serves as an ongoing method of support. Participants and facilitators encourage and support one another by commenting on posts. Figure 2 lists several examples of challenges to the participants in this independent study.

Wrap-Up Session

The wrap-up session for the THRIVE program involves a two-hour session focusing on a review of techniques learned and commitment to ongoing application. The final exercise is a dramatic reading, developed by the facilitators from the participants’ patient journaling exercise. The journaling requires each participant to take at least 30–45 minutes to thoughtfully respond to specific questions about one of his or her most significant patient experiences, either positive or negative. The question prompts are designed to elicit strong emotion toward the connection between the nurse or HCP and the patient. For the dramatic reading, the nurse or HCP speaks in the voice of the patient. The goal of the reading is for the “patients” to reflect an important message back to their nurses and HCPs about the resilience that occurred as an outcome of their therapeutic relationship. This is consistently a powerful and poignant moment for the group and individuals.

Measures

The Compassion Fatigue Short Scale (CFSS) and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) were used to evaluate the effects of the THRIVE program. All participants completed a survey prior to the first day of the program and again at its completion. For the CFSS, all participants were asked to rate the frequency of how often each of the 13 items applied to them on a 10-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (rarely or never) to 10 (very often). In previous studies, factor analysis indicated that the CFSS measures two key underlying dimensions, secondary trauma and job burnout (Bride, Radey, & Figley, 2007; Sun, Hu, Yu, Jiang, & Lou, 2016). In a multivariate model, these dimensions were related to psychological distress, even after other risk factors were controlled (Sun et al., 2016). Internal consistency estimates are 0.9 for the burnout subscale, 0.8 for the secondary trauma subscale, and 0.9 for the combined scale (Bride et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2016).

The CD-RISC was developed after years of study on victims of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when Connor and Davidson (2003) noted that resilience, a key factor in mitigating PTSD, was missing from other tools. In previous studies of this scale, including in the oncology setting, the CD-RISC has been validated with good reliability (alpha = 0.85) and validity to differentiate individuals functioning well after adversity from those who are not (Connor & Davidson, 2003; McFarland & Roth, 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019). In evaluating the outcomes of the THRIVE program with the CD-RISC, all participants rated each of the 25 statements from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (being true nearly all of the time). The total score was tallied by summing scores from each of the 25 statements, with higher scores indicating greater resilience.

To interpret the results comparably, scores on each of the scales were transferred to a 0–100 scale. The optimal preference would show resilience scores to be as high as possible, and burnout and secondary trauma to be as low as possible. There are no standard interpretable scores for oncology HCPs on these scales; rather, they are used to compare groups and to compare pre- to postprogram results. Also, for the first year of the program, in addition to the before and after self-assessments, all participants were surveyed at two months, four months, and six months after the program to assess for sustained change in resilience over time. All surveys were collected by one of the original developers of the THRIVE program and stored as nonidentifiable data in locked files or on a secured network. Data were reported back to participants as pre- and postprogram assessments for the entire group only. The pre- and postprogram assessments were reported out to each group by email within several weeks of the completion of the program.

Results

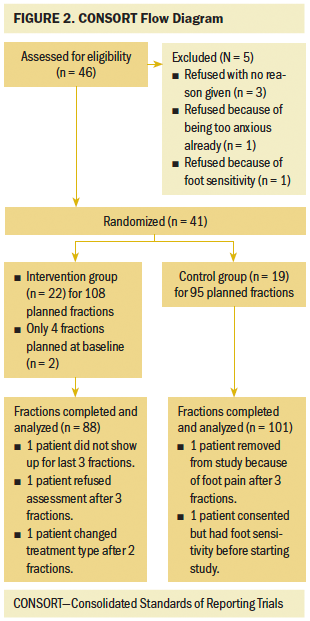

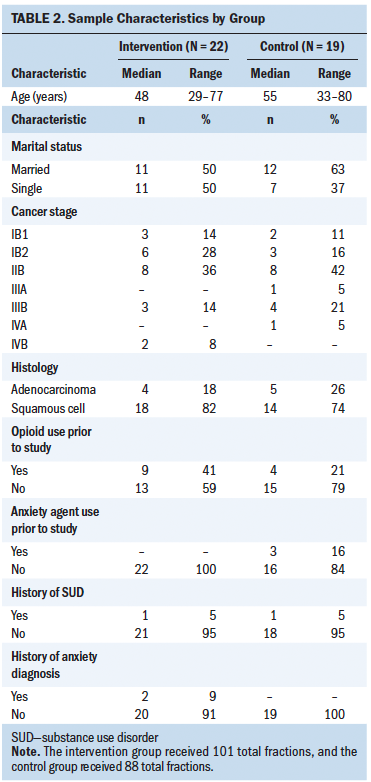

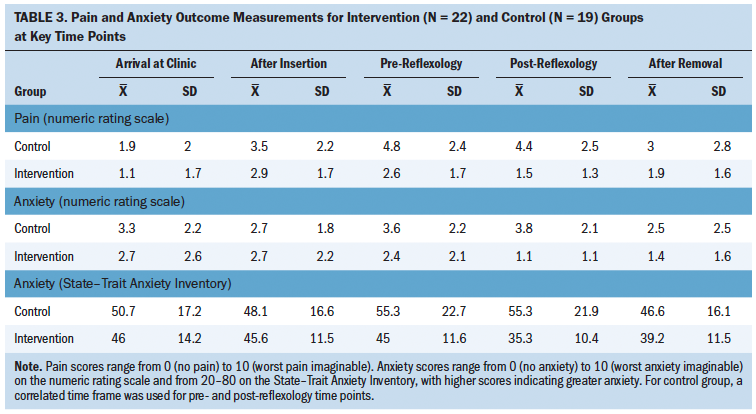

Participants in the THRIVE program represented many different roles in addition to the bedside/chairside nurse, which was the original focus of the program. All participants worked in inpatient or ambulatory settings and primarily with patients with cancer. Developers of the program wanted to begin by identifying what baseline differences may exist in the resilience and compassion fatigue of those in different roles who presented for the program. Table 2 demonstrates those baseline scores by role, prior to receiving the program interventions. Facilitators also completed only the baseline survey to demonstrate support skills for this program; they scored highest in resilience and lowest in burnout and secondary trauma when compared to all other participants. In addition, the nurse manager group scored the lowest for resilience and the highest for burnout in the preprogram assessments. Also noteworthy is that bedside/chairside nurses and advanced practice professionals scored highest in secondary trauma.

To date, the program has been conducted 10 times with a total of 164 participants since 2016. The program is conducted on the campus of the medical center, but away from usual work areas, to help create the feeling of a retreat. Small groups are preferred, particularly for some of the thought-sharing and storytelling exercises; therefore, each session has two facilitators with no more than 24 total participants. The facilitator group originally consisted of the two developers of the program; however, the group has expanded to nine trained facilitators consisting of CNSs, managers, and staff nurses who showed particular interest and expertise in some of the self-care strategies that were demonstrated. All facilitators attended the program first as participants, attended a two-hour facilitator training, and participated in sessions while being precepted by previous facilitators. Facilitator practice is guided by a facilitator manual to help keep the content consistent.

The average pre- to postprogram assessment scores for all groups combined demonstrate a greater than 10-point rise in the resilience scores (from 72 to 85), and an even greater decrease in burnout (from 41 to 23) and secondary trauma scores (from 32 to 19). The scores that demonstrated the greatest degree of change from pre- to postprogram assessment were the burnout scores. Resilience was assessed using the CD-RISC. In this study, possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. In the current study, the CD-RISC had strong internal consistency reliability (alpha = 0.92). CD-RISC scores increased significantly pre- to postprogram assessment (t = 2.64, df = 9, p = 0.0268). Burnout and secondary trauma were assessed using the CFSS. In this study, possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater burnout and secondary trauma. In the current study, the CFSS had strong internal consistency reliability (alpha = 0.84 for burnout and 0.88 for secondary trauma). The burnout and secondary trauma scores decreased significantly from pre- to postprogram assessment (t = 5.66, df = 4, p = 0.005 for burnout; t = 3.23, df = 19, p = 0.004 for secondary trauma).

The increased resilience scores for the first-year participants of the THRIVE program, who were all RNs, were maintained for at least a six-month period (see Table 3). The average yearly RN turnover rate for THRIVE program participants was 6.1%, which compares favorably to the average U.S. hospital rate of 17.1% (NSI Nursing Solutions, 2019).

Discussion

Role delineation preprogram assessment scores seem to indicate, at least in this small population of nurse managers, that burnout may be a more significant problem than for other professional caregivers. It is not surprising, perhaps, that preprogram assessment scores for bedside/chairside nurses and APRNs indicated the highest level of secondary trauma in the sample. This usually occurs in staff who are most directly exposed to the difficult clinical experience. Pre- to postprogram assessment score comparisons indicate that the program positively affects resilience, burnout, and secondary trauma, and that increased resilience scores are maintained for at least six months after the program. Turnover rates were originally studied when the facilitator checking the program waiting list noted that, on one occasion, many of the staff on the list had already left the institution. Retention rates confirm that the turnover rate is lower for those who attended the program.

Limitations of this project are that the program itself requires an investment in time from staff and support of the investment by leaders. A six-week program is a significant time investment; however, results reflect a positive outcome from that investment. Another limitation is that, although the overall sample is adequate, some of the roles delineated are much smaller than the RN sample. This reflects that the program was originally targeted to the RN, but then quickly expanded to other HCPs when program effectiveness and popularity were realized. The sample is limited to one institution, and, therefore, the institutional culture could limit its generalizability. Also, because the program was determined not to be a research study, detailed demographics were not collected from the participants. This limits the ability to compare scores based on length of time in a specific role. Because staff self-selected the program rather than being randomized to it versus another intervention, it may be surmised that staff who register are more amenable to this type of program and, relatedly, may have a greater response.

Strengths of the program, when compared with others, include the active participation and support group feel of the experience. The drawback is that this translates to training groups that are kept to a small number of participants for each session (a maximum of 12 participants per facilitator). The other unique strength of the program is the relative long-term follow-up with application of new skills. This program strength is confirmed by participants who actively engage in self-care more regularly at the completion of the program.

Additional study should be conducted with respect to resilience work and include all HCP roles. Quality studies could be strengthened through actual randomized controlled trials. Outcomes measures could be strengthened by assessing pre- and postprogram error rates, absenteeism, and staff engagement.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses and other HCPs must start to recognize the potential for detrimental effects of long-term exposure to patient trauma. As Remen (1996) stated: “The expectation that we can be immersed in suffering almost daily and not be affected by it is as unrealistic as expecting to be able to walk through water and not get wet” (p. 21).

Self-care builds resilience and deceases burnout and secondary trauma, but most nurses still view primary methods of self-care as pedicures and massages. Although these do demonstrate comforting methods, there are many more methods that can be more readily accessed, even in the middle of a stressful shift. Self-care is a joint responsibility—of the institution to offer programs that meet a variety of staff needs, and that of the individual staff member to self-reflect, select methods that work for that individual, and then apply those methods regularly. Self-care for staff can be viewed as another form of personal protective equipment in an environment that non-medical workers may never experience.

Related specifically to the current data, it is evident that the manager role is one that needs more attention. Although the current study’s population of nurse managers was small, their scores demonstrated a high degree of burnout. Burnout scores for this group did improve after the program. The developers of the THRIVE program are currently reviewing several sections of content to tailor those sections to be more specific to nursing leaders and plan to target this group more in the future. In addition to the focus on bedside/chairside nurses, this work will be expanded to include all HCPs that might be helped with resilience work.

Conclusion

Resilience programs can be an effective way of building staff resilience and decreasing staff burnout and secondary trauma. This can lead to oncology HCPs who are more engaged, more responsive and creative in their care, more dependable, and less prone to mistakes. This, in turn, leads to higher patient satisfaction and higher quality indices. Patients with cancer enter oncology care with great vulnerability and, as such, deserve staff who are not only skilled and knowledgeable, but also prepared to stand by them when the crises of diagnosis, treatment, and outcome are apparent. Oncology nurses can be leaders in this area if given the opportunity to learn new skills, the support to apply them over time, and the self-knowledge to realize what a difference could be made in a long-term career focusing on patients with cancer.

About the Author(s)

Lisa M. Blackburn, MS, APRN-CNS-BC, AOCNS®, is a clinical nurse specialist, Kathrynn Thompson, MS, APRN-BC, PMHCNS-BC, and Ruth Frankenfield, RN, MS, PMHCNS-BC, are mental health clinical nurse specialists, Anne Harding, ATR-BC, is an art therapist, and Amy Lindsey, MS, APRN-CNS, PMHCNS-BC, is a mental health clinical nurse specialist, all at the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus. No financial relationships to disclose. Blackburn, Thompson, and Harding contributed to the conceptualization and design. Blackburn and Harding completed the data collection. Blackburn provided analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Blackburn can be reached at lisa.blackburn@osumc.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2019. Accepted July 29, 2019.)

References

American Nurses Association. (2017). Executive summary: American Nurses Association health risk appraisal. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/~495c56/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/hea…

Aycock, N., & Boyle, D. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13, 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1188/09.CJON.183-191

Bride, B.E., Radey, M., & Figley, C.R. (2007). Measuring compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-007-0091-7

Burkhardt, P., & Nagai-Jacobson, M.G. (2015). Tips for spiritual caregiving. Beginnings, 35(5), 6–7.

Caley, L., Pittordou, V., Adams, C., Gee, C., Pitkahoo, V., Matthews, J. . . . Muls, A. (2017). Reflective practice applied in a clinical oncology research setting. British Journal of Nursing, 7(16), S4–S17. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.16.S4

Cleary, M., Kornhaber, R., Thapa, D.K., West, S., & Visentin, D. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 71, 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.10.002

Connor, K.M., & Davidson, J.R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Corso, V.M. (2012). Oncology nurse as wounded healer: Developing a compassion identity. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 448–450. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.CJON.448-450

Denigris, J., Fisher, K., Maley, M., & Nolan, E. (2016). Perceived quality of work life and risk for compassion fatigue among oncology nurses: A mixed-methods study [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43, E121–E131. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.ONF.E121-E131

Dyrbye, L.N., Trockel, M., Frank, E., Olson, K., Linzer, M., Lemaire, J., . . . Sinsky, C.A. (2017). Development of a research agenda to identify evidence-based strategies to improve physician wellness and reduce burnout. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166, 743–744. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2956

Feen-Calligan, H., McIntyre, B., & Sands-Goldstein, M. (2009). Art therapy applications of dolls in grief recovery, identity, and community service. Art Therapy, 26, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2009.10129613

Fetter, K.L. (2012). We grieve too: One inpatient oncology unit’s interventions for recognizing and combating compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 559–561. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.CJON.559-561

Gorski, D. (2019). Are medical errors really the third most common cause of death in the U.S.? Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved from https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/are-medical-errors-really-the-third-mo…

Grafton, E., Gillespie, B., & Henderson, S. (2010). Resilience: The power within. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37, 698–705. https://doi.org/10.1188/10.ONF.698-705

Henry, B.J. (2014). Nursing burnout interventions: What is being done? Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.CJON.211-214

Kane, L. (2019). Medscape national physician burnout, depression, and suicide report, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-60…

Kelly, L., Runge, J., & Spencer, C. (2015). Predictors of compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction in acute care nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47, 522–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12162

Kelly, L.A., & Lefton, C. (2017). Effect of meaningful recognition on critical care nurses’ compassion fatigue. American Journal of Critical Care, 26, 438–444. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2017471

Koloroutis, M. (Ed.). (2004). Relationship-based care: A model for transforming practice. Minneapolis, MN: Creative Health Care Management.

Lane, B., Cannella, K., Bowen, C., Copelan, D., Nteff, G., Barnes, K., . . . Lawson, J. (2012). Examination of the effectiveness of peppermint aromatherapy on nausea in women post C-section. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 30, 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010111423419

Lee, S.O., & Hwang, J.H. (2011). Effects of aroma inhalation method on subjective quality of sleep, state anxiety, and depression in mothers following cesarean section delivery. Journal of Korean Academy of Fundamentals of Nursing, 18, 54–62.

Lua, P.L., & Zakaria, N.S. (2012). A brief review of current scientific evidence involving aromatherapy use for nausea and vomiting. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18, 534–540. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0862

McFarland, D.C., & Roth, A. (2017). Resilience of internal medicine house staff and its association with distress and empathy in an oncology setting. Psycho-Oncology, 26, 1519–1525. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4165

Najjar, N., Davis, L.W., Beck-Coon, K., & Doebbeling, C. (2009). Compassion fatigue: A review of the research to date and relevance to cancer-care providers. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308100211

NSI Nursing Solutions. (2019). 2019 national healthcare retention and RN staffing report. Retrieved from http://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Files/assets/library/retention-insti…

Orellana-Rios, C.L., Radbruch, L., Kern, M., Regel, Y.U., Anton, A., Sinclair, S., & Schmidt, S. (2017). Mindfulness and compassion-oriented practices at work reduce distress and enhance self-care of palliative care teams: A mixed-method evaluation of an “on the job” program. BMC Palliative Care, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0219-7

Patricolo, G.E., LaVoie, A., Slavin, B., Richards, N.L., Jagow, D., & Armstrong, K. (2017). Beneficial effects of guided imagery or clinical massage on the status of patients in a progressive care unit. Critical Care Nurse, 37, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2017282

Perry, B., Toffner, G., Merrick, T., & Dalton, J. (2011). An exploration of the experience of compassion fatigue in clinical oncology nurses. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 21, 91–105.

Rao, N., & Kemper, K.J. (2017). The feasibility and effectiveness of online guided imagery training for health professionals. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 22, 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587216631903

Reimer, N. (2014). Creating moments that matter: Strategies to combat compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 581–582. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.CJON.581-582

Remen, R.N. (1996). Kitchen table wisdom: Stories that heal. New York, NY: Riverhead.

Sullivan, C.E., King, A.R., Holdiness, J., Durrell, J., Roberts, K.K., Spencer, C., . . . Mandrell, B.N. (2019). Reducing compassion fatigue in inpatient pediatric oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 46, 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.ONF.338-347

Sun, B., Hu, M., Yu, S., Jiang, Y., & Lou, B. (2016). Validation of the Compassion Fatigue Short Scale among Chinese medical workers and firefighters: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 6, e011279. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011279

Tarantino, B., Earley, M., Audia, D., D’Adamo, C., & Berman, B. (2013). Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of a pilot integrative coping and resiliency program for healthcare professionals. Explore, 9, 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2012.10.002

Wilkinson, R.A., & Chilton, G. (2013). Positive art therapy: Linking positive psychology to art therapy theory, practice, and research. Art Therapy, 30, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2013.757513

Zander, M., Hutton, A., & King, L. (2010). Coping and resilience factors in pediatric oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 27, 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454209350154