Meaning Making and Religious Engagement Among Survivors of Childhood Brain Tumors and Their Caregivers

Purpose: To describe how adolescent and young adult survivors and their mother-caregivers ascribe meaning to their post–brain tumor survivorship experience, with a focus on sense making and benefit findings and intersections with religious engagement.

Participants & Setting: Adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors and their families, living in their community settings.

Methodologic Approach: Secondary analysis of simultaneous and separate individual, semistructured interviews of the 40 matched dyads (80 total interviews) occurred using conventional content analysis across and within dyads. Meaning is interpreted through narrative profiles of expectations for function and independence.

Findings: Participants made sense of the brain tumor diagnosis by finding benefits and nonbenefits unique to their experiences. Meaning was framed in either nonreligious or religious terms.

Implications for Nursing: Acknowledging positive meaning alongside negative or neutral meaning could enhance interactions with survivors, caregivers, and their families. Exploring the meaning of their experiences may help them to reconstruct meaning and reframe post-tumor realities through being heard and validated.

Jump to a section

The sequelae of treatment for survivors of childhood brain tumors radically recast survivors’ physical, cognitive, and psychosocial realities (Turner, Rey-Casserly, Liptak, & Chordas, 2009). Many children diagnosed with a brain tumor live into adulthood because three-quarters survive at least five years after treatment without evidence of disease recurrence (Noone et al., 2018). They generally do so in families and often with one parent (usually the mother) acting as primary caregiver in addition to assuming regular parenting responsibilities. Parents and survivors often experience diagnosis- and treatment-related post-traumatic stress symptoms during survivorship (Bruce, Gumley, Isham, Fearon, & Phipps, 2011). Parents of survivors of childhood brain tumors are caregivers for many years during and after treatment, and they undergo reevaluations of their understandings of and expectations for their and their children’s lives. They frequently and consciously seek to understand their daily lives and the stark changes in the child’s life, in the family members’ lives, and in their expectations of their child, the family, and themselves. These changes can be productively understood through meaning making, and they often interact with an individual’s or family’s religious engagement.

Background

Meaning Making

Meaning making, theoretically refined by Park (2010), is used by individuals and families as they reorient themselves following stressful life experiences. Meaning making was originally defined by Park and Folkman (1997) as a model of coping that distinguishes between specific, appraised, and contextual experiences and a global meaning that reflects one’s understanding of reality in general. It unites global meaning and contextual experiences after an event requiring meaning appraisal and resolves the (potentially new) experiences with global meaning.

Meaning making has been investigated among parents after their child’s death (Lichtenthal, Currier, Neimeyer, & Keesee, 2010; Meert et al., 2015) and among adult survivors of cancer (Park, Edmondson, Fenster, & Blank, 2008). Much of the literature concerning survivors of childhood cancers focuses on positive outcomes of the cancer experience (Duran, 2013; Michel, Taylor, Absolom, & Eiser, 2010) and often only with caregiver perspectives (Gardner et al., 2017). Some studies have investigated the dual reality of being disease-free but not healed (Cantrell & Conte, 2009).

Another key part of the current study’s theoretical orientation includes Davis, Nolen-Hoesksema, and Larson’s (1998) articulation of two primary components of meaning making: sense making (why the event happened) and benefit finding (consequences of sense making to reorient the experience in a positive way). For many individuals experiencing traumatic life events, religious engagement plays a prominent role in how individuals make sense of and find benefit from illness experiences.

Religious Engagement

Many challenges exist in operationally defining and framing religious engagement in the context of scientific investigation because such engagement is heterogeneous (Park et al., 2017). In this article, religious engagement is identified by the participants in their descriptions of how they engaged with religion or spirituality specifically in the context of their meaning making about the brain tumor and survivorship experiences. Their engagement includes but is not limited to religious identity and participation. Religion and religious engagement have been investigated in the context of meaning making as they broadly relate to adversity (Park, 2005). Within Park’s (2005) model, religion and religious engagement can influence the meaning of stressors and the options available after experiences of adversity, and they can even lead to changes in one’s understanding of local and global worldviews.

Meta-analyses investigating the associations between religion and spirituality and physical (Jim et al., 2015), mental (Salsman et al., 2015), and social health (Sherman et al., 2015) in patients with cancer suggest that, at the very least, attending to patients’ religious and spiritual needs should be included in comprehensive cancer care. Such investigations are generally lacking among cancer survivors, including among survivors of childhood cancers. In addition, the significant clinical impact of religious engagement and healthcare communication has been only sporadically studied. Most investigations have generally concluded that clinicians lose patients’ confidence when their religious engagement is disregarded, and mutually defined goals of care are more often met when patients’ religious needs are prioritized (Mir & Sheikh, 2010; Ruijs et al., 2012; Tullis, 2010).

Theoretical Framing

The study’s theoretical framing includes understandings of meaning making and religious engagement existing within a broader theoretical framing that can be understood within a socioecological model, or lifeworld. Part of this theoretical orientation includes Good’s (1994) thesis that extreme experiences lead to an “unmaking of the lifeworld” and that those experiences require personal and social narratives, such as meaning making and religious engagement, “to counter this dissolution and to reconstitute the world” (p. 118). Although Good (1994) focuses on accounts of chronic pain, similar fruitful interpretive potential can be observed in the childhood brain tumor survivor population. Contending with “serious suffering is almost always about ultimate meanings . . . about what ultimately matters in a particular local world” (Kleinman, 1995, p. 50). To identify meanings, the local world of the survivor of a childhood brain tumor must also be identified. Although such worlds vary for each survivor, they most often include the self (survivor) and the one individual who is closest to the survivor (primary caregiver). The survivor and caregiver as a dyad reside in the center of this study’s socioecological model. As such, within-dyad interactions were conceptualized using symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969) to capture the meanings, management activities (responding to the meanings), and consequences of the management activities.

In a study designed to better understand caregiving competence and demand (Deatrick et al., 2014) and the quality of life of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors (Barakat et al., 2015; Hobbie et al., 2016), participants spontaneously discussed meaning making in the context of religious engagement about the brain tumor and survivorship experience. Although meaning making and religious engagement were not subjects of the interviews in the primary study, they were substantially embedded within the narratives of every participant. Following standards of qualitative research, the current authors have reported these findings because they are important to the participants.

Purpose

The purpose of the current study is to describe themes of meaning making among 40 dyads of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors and their mother-caregivers, with a focus on sense making and benefit finding and intersections with religious engagement. Using Park’s (2010) theoretical conception of meaning making, the current authors remain open to the participants’ narratives to add to understanding of meaning making in this population; as such, the current authors also discuss nonbenefit findings (neutral or negative consequences) to meaning making in this population.

Methods

The institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia granted approval for the primary study prior to data collection and analysis. Written informed consent or assent, as age appropriate, was obtained from all participants. All study data used for this secondary analysis were de-identified.

Participants

This is a secondary analysis of a primary study of caregiving competence and demand (Deatrick et al., 2014) and survivor quality of life (Barakat et al., 2015; Hobbie et al., 2016). Participants in the primary study were initially recruited from the patient populations of the neuro-oncology service and the cancer survivorship clinic of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia from 2008 to 2010; they were recruited either in the clinic or via mail. Survivors of childhood brain tumors at least five years from diagnosis and two years from treatment cessation who were aged 14–40 years were eligible to participate in this study.

Caregivers of these survivors live with the survivor and assume a major responsibility for the survivor’s care. Potential caregiver participants were not eligible for study participation if any of the following criteria were met:

• Caregiver aged younger than 21 years

• Survivor living in a partnered relationship

• Survivor diagnosed with an intellectual disability or developmental delay prior to cancer

• Survivor had genetically based cause of brain tumor (e.g., neurofibromatosis).

• Caregiver or survivor unable to speak English

The primary study’s initial recruitment was for the quantitative first phase. Data presented in this article come from the qualitative second phase of the primary study. Dyad participants in this second phase were recruited from the first phase participant pool from 2009 to 2011 and were purposively selected for maximum variation (Patton, 2002) based on the primary study’s aims.

Data Collection and Preparation

In the primary study, dyads were invited to participate in semistructured, face-to-face interviews that were conducted simultaneously but separately in the family’s home. Caregiver interviews were performed by the fourth author; caregivers were asked about their children’s brain tumor story, about the kinds of demands placed on the family and the caregiver, and how they felt about their caregiving ability. Survivor interviews were performed by the first author; similar questions were asked about the survivor’s brain tumor story, daily life, function, and family. Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. After transcription, the primary study team reviewed transcripts for accuracy and removed any participant identification. ATLAS.ti, version 7.0, was used to manage data and facilitate analyses.

Data Analysis

Narrative profile formation, briefly described in this article and extensively discussed in this population elsewhere (Lucas, Barakat, Jones, Ulrich, & Deatrick, 2014), was selected because it allows the collected data to be placed within the context of the participants’ lives and stories. Following conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), which proceeds inductively based on the data, interviews were coded separately by two of the current authors, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Codes were added, edited, removed, or combined as necessary during data analysis, and interviews coded early in the analysis process were reviewed for coding accuracy after code lists were finalized. All presented names are pseudonyms, with the first letter of the pseudonym common within caregiver–survivor dyads (e.g., Brenda and Brandon, Irene and Isabella). Because the caregiver and the survivor make up an interactive dyad, analysis focused not only on reviewing data across the entire sample but also within each survivor–caregiver dyad.

Within-dyad interaction was conceptualized using symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969). The purpose of viewing dyads’ relationships in this way was to be exploratory and to ensure appropriate contextualization of the dyads’ expectations for function and independence and how they responded to those expectations.

The analysis by Lucas et al. (2014) revealed four distinct narrative profiles of function and independence of the survivor. Each profile describes dyads in which the survivor and caregiver generally agreed (convergent) or disagreed (nonconvergent) about the survivor’s present and future function and the survivor’s ability to live independently in the future, listed as follows:

• Profile A: convergent expectations about an optimistic future

• Profile B: convergent expectations about a less optimistic future

• Profile C: nonconvergent expectations about a less optimistic future

• Profile D: nonconvergent expectations about an unclear future

Dyads both do well and/or struggle in systematically different manners in each profile (Lucas et al., 2014). The results of the present analysis were embedded onto the four profiles to better illuminate meaning making in the context of expectations for function and independence within each dyad.

From the context of how members of each dyad managed caregiving, oneself, each other, and the multiple chronic conditions of their survivorship, they also described how they made sense of the brain tumor and survivorship and found benefits and nonbenefits, or consequences. The context of their meaning making was also organized by intersections with emerging themes about religious engagement, as identified by the participants.

Consistent with symbolic interactionism and social constructionism, meaning making is not only deeply embedded within the family but also within the realities of the research team (Hosking & Pluut, 2010). As such, analytic rigor reported in this manuscript is strengthened with those systematic efforts at designing and controlling methods and by the process of reflexivity (Finlay, 2002) on the part of the research team. These systematic efforts included maintenance of an audit trail of all methodologic decisions, meeting memos, and analytic decisions, as well as an interprofessional approach to analysis and interpretation. Because this is a secondary analysis, it was not possible to re-interview participants to confirm interpretations of their statements about meaning making; however, meaning is made and reality is constructed through narratives (Ferber, 2000). The authors contend that meaning can be remade and reality can be reconstructed through narratives as well, and they acknowledge their active role in this process as played by researchers.

Results

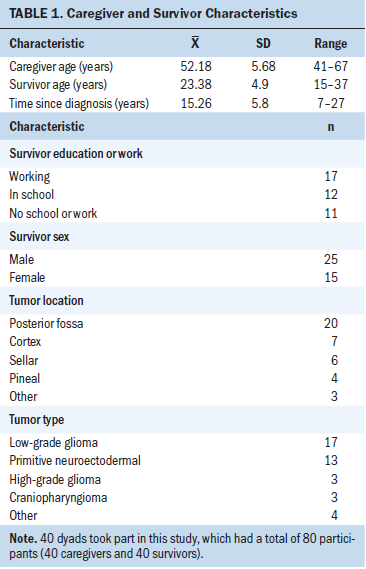

Forty caregiver–survivor dyads participated in the qualitative second phase of the primary study, and all 40 dyads are included in this secondary analysis. Dyad demographics (see Table 1) did not differ from the full complement in the primary study (Deatrick et al., 2014). The meaning making components captured in the interviews include the outcomes of their sense making and benefit and nonbenefit findings. Dyads described how the families find benefit (positive consequences) and made the case for nonbenefits (neutral and negative consequences) as being essential to their meaning making. Nonbenefit findings occurred when dyads acknowledged how they continued to live with struggles generally related to the treatment sequelae.

Meaning Making

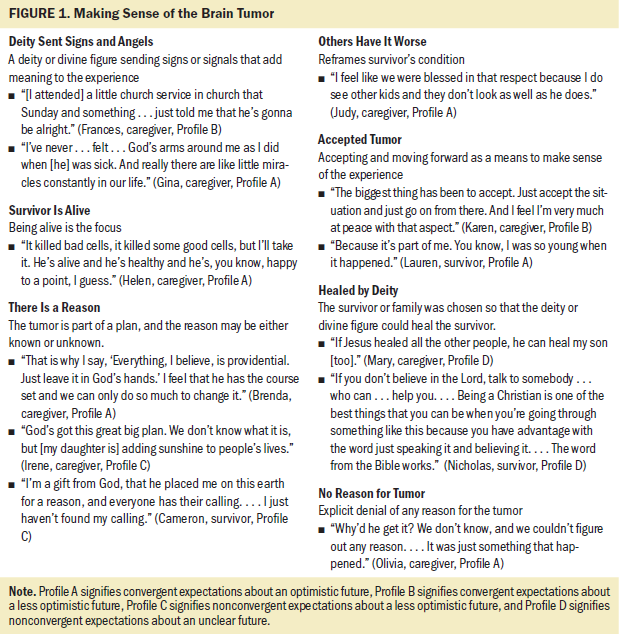

Sense making: Seven themes concerning how the dyads made sense of the brain tumor and survivorship experience were identified (see Figure 1). The most frequently cited way of making sense was to state that the survivor is still alive. This and other themes referred to personal perspectives on various aspects in their worlds, including the survivor, other survivors, the mother-caregiver’s caregiving, and a higher deity. All focused on struggles with acceptance, healing, and being saved from the brain tumor. Even those who saw no reason for the tumor referred to trying to figure it out and came to the understanding that no reason existed.

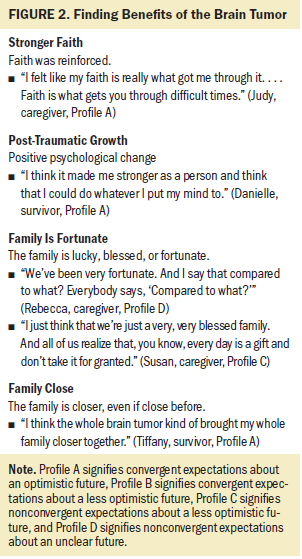

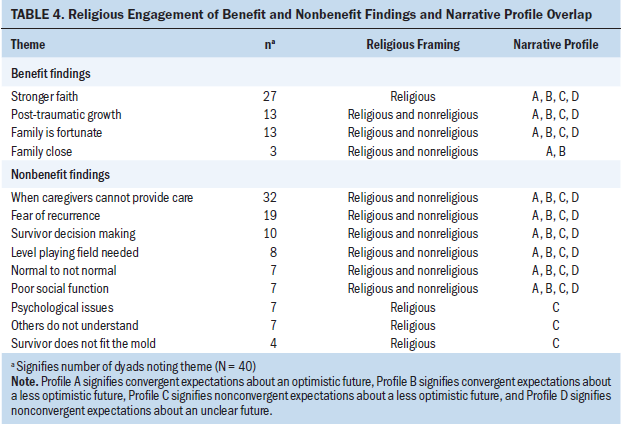

Benefit and nonbenefit findings: The dyads identified several benefits and nonbenefits of the brain tumor and survivorship experience, which coded to four distinct benefit findings (see Figure 2) and nine nonbenefit findings (see Figure 3). The majority of the dyads found stronger faith: “I guess he brought me more to religion than I had had previously,” said Patricia, mother of Patrick, a 17-year survivor of a craniopharyngioma. Many discussed how they saw the family as fortunate and noted post-traumatic growth in the survivor; some, although not all, reported that they found the family to be closer as a result of this experience.

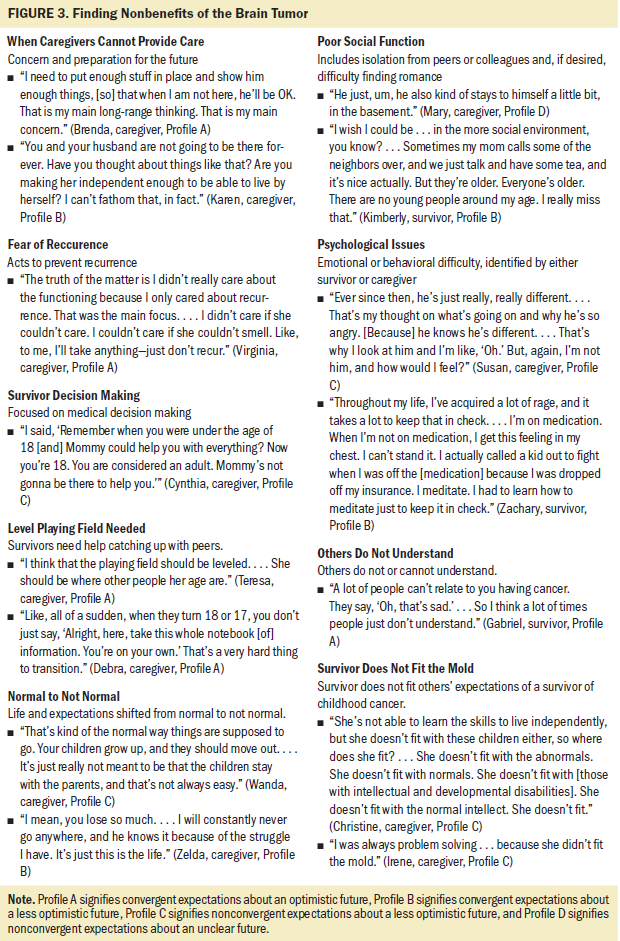

Nine themes regarding meaning outcomes of the brain tumor and survivorship experience clearly were findings for the family but were not benefits. Overwhelmingly, caregivers and survivors were concerned about a time in the future when the caregiver would no longer be able to provide care. A common hope was that the caregiver could prepare the survivor, but a fear was that no amount of preparation would be enough. Many participants had very real fears about potential tumor recurrence. Several caregivers continued to mourn the loss of their expectations for a perceived normal life that is often related to the survivors’ social or psychological functional struggles.

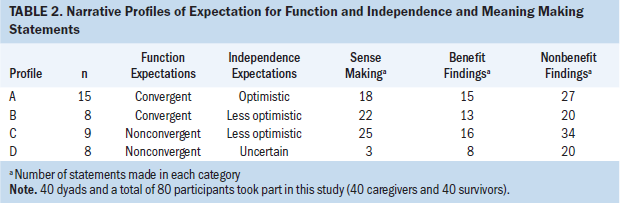

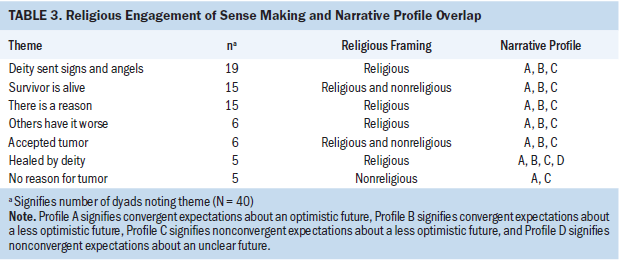

Meaning making and narrative profiles of expectations: The survivor–caregiver dyads represented within the four narrative profiles (Lucas et al., 2014) volunteered various types of meaning making statements (see Table 2). No dyad exclusively expressed benefit or nonbenefit findings, and within each profile, dyads discussed nonbenefit findings 2.25 to 3.5 times more than benefit findings. Dyads with nonconvergent expectations for function (Profiles C and D) expressed more nonbenefit findings to a greater extent than did profiles with convergent expectations for function (Profiles A and B). In other words, dyads with nonconvergent expectations for function and a less optimistic future (Profile C) discussed nonbenefit findings more (40%–70% more statements) than did dyads in the other profiles. Dyads with nonconvergent expectations for function and an uncertain future (Profile D) expressed the fewest sense-making statements and primarily focused on religious rationales.

Religious Engagement

Although it was not a specific demographic or interview question, 38 dyads volunteered a religious identity: Christian in all dyads except one, which identified as combination Hindu/Buddhist. The latter dyad did not frame its meaning making with religious material. Expressions of the key role of religion varied, and interviews were coded in one of three ways: (a) nonreligious in meaning making, (b) religion as explanation, and (c) religion as cause. The intersections of religious framing and meaning making with dyadic narrative profiles (of expectations for future function and independence), sense making, and benefit and nonbenefit findings appear in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Nonreligious in meaning making: About one-third of dyads (n = 13) either did not mention religious material in the context of making meaning about the brain tumor and the survivorship experience or did so only a few times and in passing. This does not mean that the dyads were not religious or did not find meaning in religious engagement; instead, it indicates that their discussions of making sense of and finding benefits and nonbenefits from the brain tumor and survivorship experience did not include religion. Sense making by these dyads often included the conception that there was no reason a child should get a brain tumor. Andrew, a 17-year survivor of a primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and Angela, his mother, disagreed about function, with less optimism about independence (Profile C). Angela explained further:

I get mad when people say, “Oh, things happen for a reason.” I would like to knock them out when they say that. Who would do that to a kid for a reason? I don’t believe in that reason stuff. There’s no reason for a kid to have a brain tumor.

Making sense of the brain tumor by stating that there is no reason for it is in stark contrast to statements from the expressively religious dyads.

Religion as explanation: Most dyads (n = 19) discussed meaning making with an expressive religious framing. Occasionally (n = 2) the survivor’s religious engagement was more expressive than the caregiver’s. These dyads’ religious engagement was characterized by the following characteristics:

• Some form of Christianity for the survivor or family

• Caregiver’s approval of survivor’s choices or behaviors based on Christian norms

• Caregivers’ and survivors’ inclusion of deity or divine figure as primary yet external players in family dynamics

• Understanding that their deity is with them

• Feeling better or stronger after prayer

A quotation from Brandon, an 11-year survivor of a pineal germinoma, exemplifies religion as explanation, in which religion is used to give meaning to the brain tumor after the fact:

After the cancer, it was like God’s wake-up call for me where he said, “It is not about you anymore; there is a larger force at work.” It kind of forced me to realize that my time on this earth is limited, and I have to make the best use of every day that I am given. That is what became my new motto: “Every day is a gift. That is why they call it the present.”

This dyad agrees about Brandon’s function and has optimism about future independence (Profile A).

Religion as cause: Among the most religious dyads (n = 8), the family received direct intervention and experienced an active role played by a deity or divine figure, in which the deity chooses, gives, provides, saves, or plans for the family. In these families, the deity chooses the survivor; the power of prayer saves the survivor, causing a miracle; and the family is sent angels and miracles. Cameron, a 20-year survivor of a ventricular choroid plexus tumor, and Cynthia, his mother, disagreed about function, with less optimism about future independence (Profile C). Cynthia provided more details:

Well, it’s like God picked me for a reason. . . . He picked me to teach him how to deal with his situation, you know? And I always tell [Cameron], “You’re a miracle child. You’re here.” And I keep saying to him over and over, “You’re here for a reason. Maybe we don’t know now. Maybe we don’t know tomorrow. But in the future you will see.”

These most religious dyads went beyond believing that a deity was a primary player within the family, to believing that a deity was acting on the family, particularly the survivor. Ethan, a 12-year survivor of a posterior fossa low-grade glioma, and Elizabeth, his mother, agree about Ethan’s functional abilities and are not optimistic that he will be able to live on his own in the future (Profile B). Elizabeth revealed the following:

I certainly believe in God now. If I didn’t before, I certainly do now. . . . The power of prayer is the only thing that I can believe that saved me. . . . I put my faith in God, and I really believe that is what got me through it. I still believe that until this day. I know sometimes it can be hard for people that don’t believe, but I think Ethan was a miracle, I do. . . . Saint John Neumann has a shrine. . . . He is the patron saint of children with cancer, so we took him down the day before his surgery and got . . . the back of his head blessed with the relic, and the doctor was not sure what they were going to find. They were really very concerned that it could be cancer, and when he came out the next day telling us that it wasn’t [malignant], it was just, it blew me away. After coming home after six weeks or so, I started reading up about John Neumann and I found out that he . . . was canonized a saint on Ethan’s birthday. It just put chills down my spine, so it all felt like that is where it came from. I just really believe that.

The survivor as miracle is the ultimate indication to this family that their deity intervened on behalf of the survivor; this, in a way, justifies the survivor’s changed life course. This dyad provides an example of the intersection of made meaning with expectations for the future.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore meaning making, including religious engagement, among 40 dyads made up of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors and their mother-caregivers. The components of sense making, benefit and nonbenefit findings, and expressions of religious engagement were easily discernible in the interviews, even though the respondents were not explicitly asked about them. The study’s inclusive approach to the meaning making findings through the previously identified narrative profiles of function and independence (Lucas et al., 2014) provides a platform on which interpretation of the meaning making components is more easily understood. The survivor–caregiver dyads, for the most part, make sense of the brain tumor in the context of religion and related to a very wide range of outcomes, somewhat reflecting the potential extent of their treatment-related sequelae. All the dyads discussed benefit findings but spoke more about the nonbenefits of the brain tumor and survivorship experience. This finding indicates that negative and neutral consequences are critically important components of family life and how meaning is made. In addition, religious engagement plays a role during meaning making, and especially with nonbenefit findings among dyads with non-convergent expectations for function and less optimism for independence.

The outcomes of their sense making and benefit and nonbenefit findings are their realities. It is within these realities that they reconstruct their lifeworlds, described after several reframings of their realities. Post-traumatic growth, or self-reported positive psychological change after trauma (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004), has been widely observed among childhood cancer survivors (Barakat, Alderfer, & Kazak, 2006) and specifically among survivors of childhood brain tumors (Hocking et al., 2011). Post-traumatic growth is evident in the current study for dyads in each of the narrative profiles and potentially more among dyads with convergent expectations and an optimistic future (Profile A).

The dyads’ lifeworlds received positive reconstruction from religious framing. Cancer diagnoses have been shown to be associated with increasing religious engagement (McFarland, Pudrovska, Schieman, Ellison, & Bierman, 2013), presumably in part because “biomedicine banishes purpose and ultimate meaning to religion” (Kleinman, 1995, p. 50). Even when conducting the analyses with dyads rather than with individuals, it was clear in many cases that the caregiver—perhaps acting as a parent or a family leader—drove the incorporation of religious framing of the brain tumor. Caregivers described the brain tumor diagnosis as a catalyst for igniting the following: having strong Christian beliefs, reinforcing their current faith understandings, being discouraged by religious sentiments, or not being moved by religious engagements.

Although several levels of religious engagement were seen across the narrative profiles and throughout sense making and benefit and nonbenefit findings, the very religious only intersected profiles in which there was less optimism for the survivor to live independently in the future (Profiles B and C). It is unclear whether high religious engagement preceded the brain tumor or if religious engagement intensified during treatment or survivorship; these questions were not posed to participants. These families’ lives have a decidedly different outcome than what was originally expected: The survivor will most likely need caregiving for the rest of their life, a difference in caregiving scale and scope that may play a role in this finding.

The intersection between religious engagement and the four profiles, when looking specifically at nonbenefit findings, occurred only with dyads with nonconvergent expectations about future functioning and a less optimistic future (Profile C); these dyads often reported disagreements with clinicians. In addition, in these dyads, the survivor had profound psychological distress, believed that others did not understand or relate to the family, and felt that he or she was not fitting others’ (e.g., members of family’s community, clinicians) expectations. It is not apparent whether the families’ religious understandings of meaning were heightened as a result of interactions with clinicians or if the families had less conducive interactions with clinicians because their religious engagement or lack thereof was not understood by clinicians. These are important questions for future study.

Outcomes for the families in Profile C, relatively speaking, are the least desirable. Religion certainly plays a role in adjustment after brain tumor diagnosis and during survivorship and is considered valuable in stressful situations that push individuals to their personal limits (Pargament, 2002). The extent to which “particular kinds of religious expressions for particular people dealing with particular situations in particular social contexts according to particular criteria” (Pargament, 2002, p. 178) are either helpful or harmful is unknown. Profile C dyads have a seemingly paradoxical pattern consisting of nonconvergent views, non-plausible future survivor independence, high religious engagement, and a focus on non-benefit findings of the brain tumor and survivorship experience. Most research suggests that religious engagement generally facilitates positive adjustments to stressful situations, but because adjustments are dependent on the context and content of life changes, attention to negative aspects despite religious engagement may provide more comprehensive understandings of religion’s influences on meaning (Park, 2005). This pattern brings up questions for future study regarding the possible roles of higher religious engagement for meaning making, specifically nonbenefit findings, and clinician–patient–family communication among these dyads.

Dyads with nonconvergent expectations and an uncertain future (Profile D) had very few instances of sense making, perhaps because plausible independence is uncertain and these dyads had not yet incorporated or finalized sense making into their understandings of the brain tumor and survivorship experience. Following conclusions of Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Zhang, and Noll (2005), because these dyads generally have a younger survivor, they may be focused on recovery processes and are not yet attempting to make sense of the brain tumor.

Meaning making does not always result in finding benefits. The caregivers in the current study reported making personal and family sacrifices to give the survivors a head start. They learned to do this after having lived for years, even decades, with understandings that these outcomes are part of their stories that include a brain tumor in childhood for the survivor and the potentially accumulating treatment-related sequelae in survivorship. Where the sequelae have accumulated, so have the findings, benefit and otherwise, that are present in the structuring of their realities.

Although the meaning making model typically presents pathways that result in addressing challenges to one’s global meaning after a potentially stressful situation, it does so with a focus on positive changes and outcomes as successful changes and outcomes (Park, 2010), which is an attribute of positive psychology. Survivors of childhood brain tumors and their families do have positive understandings of their realities:

• The survivor is alive.

• The family is closer.

• The survivor and others experience post-traumatic growth.

• Faith is reinforced.

• The survivor was healed by his or her deity.

• The survivor was chosen to have the brain tumor for a reason (which is identified as positive, and the reason may or may not have been revealed).

These individuals also have neutral understandings of their realities:

• The playing field should be leveled.

• Brain tumors just happen.

• The context is reframed so that others are seen as having worse outcomes.

Families also have what amount to negative understandings of their realities:

• Changed expectations about the child’s life

• Continuous fear of recurrence

• Significant psychological issues in the survivor

• Concerns about transferring decision-making responsibility

• Others not understanding the family and not accepting the survivor

The focus on negative experiences is not intended to bring virtue to that experience, but it could be either a method of coping or an adaptive style promoting problem solving (Held, 2004). Their made meaning is constructed or reconstructed through mapping across the variety of childhood brain tumor survivorship experiences (Rentmeester, 2014), which include paradoxical experiences, uncertainty, changes in social worlds, different ways of being, and a need for external help (Woodgate, Tailor, Yanofsky, & Vanan, 2016).

The findings from this study offer compelling preliminary data to expand meaning making models to be inclusive of a wider variety of findings after a family has made sense of a brain tumor in childhood. Although an outsider may not view the nonbenefit findings in a positive light, the families might be refocusing meaning components in a way that positive is not as important (Deatrick, Knafl, & Murphy-Moore, 1999). What is normative for these families is that they each acknowledge what may be different and what may be the same and recreate their life narratives after the brain tumor, inclusive of positive and negative outcomes. This restorying is similar to that described by others (Lau & van Niekerk, 2011). The wider scope of the dyads in the current study allows us to see intrafamilial divisions in meaning making: Those who disagree on almost all accounts (Profile C) appear to feel the most alienated. However, what they do agree on is high religious engagement.

These benefit and nonbenefit findings mirror the struggles found among other cohorts of childhood brain tumor survivors, including general competence (Boydell, Stasiulis, Greenberg, Greenberg, & Spiegler, 2008), independent living (Kunin-Batson et al., 2011), and social function (Schulte & Barrera, 2010). Competence, independent living, and social function, along with making meaning, are largely sociocultural constructions. Many of the dyads found meaning in religion; none referenced any aspect of the healthcare realm in their meaning making.

Limitations

Because the current study is a secondary analysis, the authors were not able to directly ask the caregivers and survivors to attribute meaning to their brain tumor and survivorship experiences. However, the dyads did spontaneously talk about meaning and included religious engagement. The dyads’ discussion of the meaning content may be an almost evangelical act for some, in part because many of the dyads were very religious. All dyads spontaneously discussed sense making and benefit and nonbenefit findings on their own terms because they felt that this was part of their experience that the investigators and, consequently, the wider research community should hear. As with all research and included in the informed consent, the participants well understood that this study would not immediately benefit them and would be written up for publication. It is possible that directly asking about sense making, at least in this population, may skew some of the responses in regard to religious engagement. Perhaps analyzing these data in this way has allowed for the appropriate capture of the scope of religious engagement among the families of survivors of childhood brain tumors and authentic meaning making data.

The current authors also were careful in the ways they chose to portray religious engagement. For example, the authors questioned when the sentence “they were God’s angels” ceased being a common metaphor and was instead a signifier of religious engagement. When the participant used minimal religious talk, such phrases were viewed as common metaphors; when the participant repeatedly used religious talk, they became representative of religious engagement instead. From the data, it is not possible to know if dyads’ global meanings were consistent with their pre-tumor global meanings, were in a state of flux, or were revised after sense making had been achieved. Dyads with nonconvergent expectations and an uncertain future (Profile D) did not discuss much sense making, in part because they were not directly asked about it. Because these families are younger and still struggling with the sequelae and imagined and actual threats of tumor recurrence, sense making may still be under construction or may not even be a concern for those dyads.

Implications for Nursing

Even after having survived and making sense of the brain tumor, many families still struggle. This is more clearly seen by looking at the two central individuals (i.e., survivor and caregiver) together than at either alone. There are also several differences between application of the meaning making model to survivors of childhood brain tumors and its application to other individuals or occurrences (e.g., bereavement, following natural disaster). One major difference is that the families often continue to live with the threat of tumor recurrence, which may prevent families from finalizing their sense making.

In part because nonbiomedically oriented meaning is often relegated by clinicians to the nonclinical realm, many clinicians may not feel comfortable with or know how to communicate with patients and families about meaning or any other area influenced by religious engagement or how to respond when families raise the issues directly, unless explicitly educated to do so (Deatrick et al., 2009). However, nurses and other clinicians do not need to take on the role of hospital chaplain (Mundle, 2012). Generally, all clinicians can engage with patients and families regarding their intentions, understandings, and decision-making processes.

The clinician must first accept that their job is not to fix or change meaning but rather to be present with the individual and their family so they can, over time, be better able to reframe their own experiences. There is much to learn about the experiences of long-term survivors of childhood brain tumors and their families, but the positionality of nurses being present with patients and their family members is consistent with a long-standing understanding of the essence of nursing (Covington, 2003). As such, nurses may be the ideal clinical team member to acknowledge the importance of the experience’s meaning to the patient and their family, as well as offer support as this meaning is reframed over time.

Recommendations to improve cancer survivorship care from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018) do not include content concerning meaning making and religious engagement. However, these recommendations suggest “incorporating meaningful survivor-reported and caregiver-reported outcomes . . . about what matters to them in terms of important outcomes . . . [and going] beyond the traditional standard measures” (p. 104). The approach and findings of the current study lay some of the groundwork for identifying quality measures of these meaningful outcomes that matter most to survivors and caregivers.

Although some of the participants in the current study may benefit from consultation with other professionals, like chaplains, all can certainly benefit from a simply initiated or continued conversation about their understanding of the brain tumor and the resulting decisions made by the families. During treatment, the families’ lives often revolved around clinical biomedicine, the goal of which is to eliminate the brain tumor while attempting to offer the greatest potential for future function and livelihood. However, the caregivers and survivors who participated in this study did not mention that meaning was derived from communication with clinicians. This could signify that during survivorship, clinical biomedicine is left behind. Perhaps discussions that incorporate the families’ religious framing of the brain tumor and resultant conditions (or any other incorporation of families’ values and life goals) can lead to the eventual inclusion of biomedical and clinical voices in meaning after brain tumors.

Conclusion

Survivors of childhood brain tumors and their families are different than the survivors of adult brain tumors or other childhood cancers and their families. The tumor occurs during childhood and often gravely affects social, psychological, and physiological development. As a result, the survivors’ parents shift between parenting and caregiving during the remainder of their lifetimes. Researchers can delineate between roles and offer clinicians anticipatory guidance for families on how to acknowledge and navigate the future changing roles of the parent-caregiver and the child-survivor as the child ages. Treatment-related sequelae have the potential to tremendously affect future life course. Although the benefit findings from the current study appear similar to those of other populations investigated with the meaning making model, the nonbenefit findings are novel. It is unclear if nonbenefit findings are specific to this population or if they were identified as a result of the combined focus on dyads and interview-style data collection. The authors suggest future research on meaning making that includes nonbenefit findings conducted with survivors of childhood brain tumors. It is possible that nonbenefit findings may also be terminal understandings of meaning making for others as well, because by acknowledging these, family members can move toward their own meaning.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions to improve this article.

About the Author(s)

Em Rabelais, PhD, MBE, MS, MA, RN, is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing and Department of Women, Children, and Family Health Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago; Nora L. Jones, PhD, is an associate director and assistant professor in the School of Medicine and the Center for Bioethics, Urban Health, and Policy at Temple University in Philadelphia, PA; and Connie M. Ulrich, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor in the School of Nursing and Department of Biobehavioral Health Sciences, and Janet A. Deatrick, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor emerita in the School of Nursing and Department of Family and Community Health, both at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research (F31NR013091, principal investigator [PI]: Rabelais; T32NR007100; R01NR009651, PI: Deatrick) and the American Cancer Society (122552-DSCN-10-089, PI: Rabelais) and a neuro-oncology nursing grant from the Oncology Nursing Foundation (PI: Deatrick). Rabelais, Ulrich, and Deatrick contributed to the conceptualization and design. Rabelais, Jones, and Deatrick provided the analysis. Rabelais and Deatrick completed the data collection and provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Rabelais can be reached at rabelais@uic.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted July 2018. Accepted September 14, 2018.)

References

Barakat, L.P., Alderfer, M.A., & Kazak, A.E. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj058

Barakat, L.P., Li, Y., Hobbie, W.L., Ogle, S.K., Hardie, T., Volpe, E.M., . . . Deatrick, J.A. (2015). Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Psycho-Oncology, 24, 804–811. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3649

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bonanno, G.A., Papa, A., Lalande, K., Zhang, N., & Noll, J.G. (2005). Grief processing and deliberate grief avoidance: A prospective comparison of bereaved spouses and parents in the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.86

Boydell, K.M., Stasiulis, E., Greenberg, M., Greenberg, C., & Spiegler, B. (2008). I’ll show them: The social construction of (in)competence in survivors of childhood brain tumors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 25, 164–174.

Bruce, M., Gumley, D., Isham, L., Fearon, P., & Phipps, K. (2011). Post-traumatic stress symptoms in childhood brain tumour survivors and their parents. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01164.x

Cantrell, M.A., & Conte, T.M. (2009). Between being cured and being healed: The paradox of childhood cancer survivorship. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 312–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308330467

Covington, H. (2003). Caring presence: Delineation of a concept for holistic nursing. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 21, 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010103254915

Davis, C.G., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Larson, J. (1998). Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 561–574.

Deatrick, J.A., Hobbie, W., Ogle, S., Fisher, M.J., Barakat, L., Hardie, T., . . . Ginsberg, J.P. (2014). Competence in caregivers of adolescent and young adult childhood brain tumor survivors. Health Psychology, 33, 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033756

Deatrick, J.A., Knafl, K.A., & Murphy-Moore, C. (1999). Clarifying the concept of normalization. Image, 31, 209–214.

Deatrick, J.A., Lipman, T.H., Gennaro, S., Sommers, M., de Leon Siantz, M.L., Mooney-Doyle, K., . . . Jemmott, L.S. (2009). Fostering health equity: Clinical and research training strategies from nursing education. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 25, 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70554-6

Duran, B. (2013). Posttraumatic growth as experienced by childhood cancer survivors and their families: A narrative synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30, 179–197.

Ferber, A.L. (2000). A commentary on Aguirre: Taking narrative seriously. Sociological Perspectives, 43, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389800

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research, 12, 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973202129120052

Gardner, M.H., Mrug, S., Schwebel, D.C., Phipps, S., Whelan, K., & Madan-Swain, A. (2017). Benefit finding and quality of life in caregivers of childhood cancer survivors: The moderating roles of demographic and psychosocial factors. Cancer Nursing, 40, E28–E37. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000419

Good, B.J. (1994). Medicine, rationality, and experience: An anthropological perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Held, B.S. (2004). The negative side of positive psychology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44, 9–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167803259645

Hobbie, W.L., Ogle, S., Reilly, M., Barakat, L., Lucas, M.S., Ginsberg, J.P., . . . Deatrick, J. A. (2016). Adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors: Life after treatment in their own words. Cancer Nursing, 39, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000266

Hocking, M.C., Hobbie, W.L., Deatrick, J.A., Lucas, M.S., Szabo, M.M., Volpe, E.M., & Barakat, L.P. (2011). Neurocognitive and family functioning and quality of life among young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 25, 942–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2011.580284

Hosking, D.M., & Pluut, B. (2010). (Re)constructing reflexivity: A relational constructionist approach. Qualitative Report, 15, 59–75.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jim, H.S., Pustejovsky, J.E., Park, C.L., Danhauer, S.C., Sherman, A.C., Fitchett, G., . . . Salsman, J.M. (2015). Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer, 121, 3760–3768. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29353

Kleinman, A. (1995). Writing at the margin: Discourse between anthropology and medicine. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kunin-Batson, A., Kadan-Lottick, N., Zhu, L., Cox, C., Bordes-Edgar, V., Srivastava, D.K., . . . Krull, K.R. (2011). Predictors of independent living status in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 57, 1197–1203. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22982

Lau, U., & van Niekerk, A. (2011). Restorying the self: An exploration of young burn survivors’ narratives of resilience. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 1165–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311405686

Lichtenthal, W.G., Currier, J.M., Neimeyer, R.A., & Keesee, N.J. (2010). Sense and significance: A mixed methods examination of meaning making after the loss of one’s child. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66, 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20700

Lucas, M.S., Barakat, L.P., Jones, N.L., Ulrich, C.M., & Deatrick, J.A. (2014). Expectations for function and independence by childhood brain tumor survivors and their mothers. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 4, 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2014.0068

McFarland, M.J., Pudrovska, T., Schieman, S., Ellison, C.G., & Bierman, A. (2013). Does a cancer diagnosis influence religiosity? Integrating a life course perspective. Social Science Research, 42, 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.10.006

Meert, K.L., Eggly, S., Kavanaugh, K., Berg, R.A., Wessel, D.L., Newth, C.J., . . . Park, C.L. (2015). Meaning making during parent–physician bereavement meetings after a child’s death. Health Psychology, 34, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000153

Michel, G., Taylor, N., Absolom, K., & Eiser, C. (2010). Benefit finding in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents: Further empirical support for the Benefit Finding Scale for Children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01034.x

Mir, G., & Sheikh, A. (2010). ‘Fasting and prayer don’t concern the doctors ... they don’t even know what it is’: Communication, decision-making and perceived social relations of Pakistani Muslim patients with long-term illnesses. Ethnicity and Health, 15, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557851003624273

Mundle, R.G. (2012). Engaging religious experience in stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Religion and Health, 51, 986–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9414-z

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Noone, A.M., Howlader, N., Krapcho, M., Miller, D., Brest, A., Yu, M., . . . Cronin, K.A. (2018). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2015. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Pargament, K.I. (2002). The bitter and the sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1303_02

Park, C.L. (2005). Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 707–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00428.x

Park, C.L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 257–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

Park, C.L., Edmondson, D., Fenster, J.R., & Blank, T.O. (2008). Meaning making and psychological adjustment following cancer: The mediating roles of growth, life meaning, and restored just-world beliefs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013348

Park, C.L., & Folkman, S. (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1, 115–144.

Park, C.L., Masters, K.S., Salsman, J.M., Wachholtz, A., Clements, A.D., Salmoirago-Blotcher, E., . . . Wischenka, D.M. (2017). Advancing our understanding of religion and spirituality in the context of behavioral medicine. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9755-5

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rentmeester, C. (2014). Cartography of endurance. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 4, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2014.0010

Ruijs, W.L., Hautvast, J.L., van IJzendoorn, G., van Ansem, W.J., Elwyn, G., van der Velden, K., & Hulscher, M.E. (2012). How healthcare professionals respond to parents with religious objections to vaccination: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 12, 231. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-231

Salsman, J.M., Pustejovsky, J.E., Jim, H.S., Munoz, A.R., Merluzzi, T.V., George, L., . . . Fitchett, G. (2015). A meta-analytic approach to examining the correlation between religion/spirituality and mental health in cancer. Cancer, 121, 3769–3778. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29350

Schulte, F., & Barrera, M. (2010). Social competence in childhood brain tumor survivors: A comprehensive review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18, 1499–1513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0963-1

Sherman, A.C., Merluzzi, T.V., Pustejovsky, J.E., Park, C.L., George, L., Fitchett, G., . . . Salsman, J.M. (2015). A meta-analytic review of religious or spiritual involvement and social health among cancer patients. Cancer, 121, 3779–3788. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29352

Tedeschi, R.G., & Calhoun, L.G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

Tullis, J.A. (2010). Bring about benefit, forestall harm: What communication studies say about spirituality and cancer care. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 11(Suppl. 1), 67–73.

Turner, C.D., Rey-Casserly, C., Liptak, C.C., & Chordas, C. (2009). Late effects of therapy for pediatric brain tumor survivors. Journal of Child Neurology, 24, 1455–1463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073809341709

Woodgate, R.L., Tailor, K., Yanofsky, R., & Vanan, M.I. (2016). Childhood brain cancer and its psychosocial impact on survivors and their parents: A qualitative thematic synthesis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20, 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2015.07.004