Cancer Prehabilitation Programs and Their Effects on Quality of Life

Problem Identification: Cancer prehabilitation programs have been reported as effective means of improving quality of life (QOL) in people with cancer, but research is lacking. The aim of this systematic review is to explore the characteristics of cancer prehabilitation programs and their effects on QOL in people with cancer.

Literature Search: A systematic review of databases (PubMed, MEDLINE®, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CINAHL®, Scopus®) was performed using key terms.

Data Evalution: Data were extracted, and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale was used to assess the quality of the studies.

Synthesis: 12 randomized, controlled trials with a total of 839 people with cancer were included in this review. Of these, seven cancer prehabilitation programs focused on physical interventions, three focused on psychological interventions, and two focused on multimodal interventions.

Implications for Nursing: Oncology nurses could provide various cancer prehabilitation programs to patients who decide to undergo cancer-related treatment. Additional research on this subject should involve careful consideration of QOL instruments and sample size when designing the intervention.

Jump to a section

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, with about 1 in 6 deaths attributable to the disease (World Health Organization, 2018). After diagnosis, many people with cancer experience physical and psychological symptoms, as well as a financial burden on themselves and their families and a decrease in quality of life (QOL) (Astrup, Rustøen, Hofsø, Gran, & Bjordal, 2017; Große, Treml, & Kersting, 2018).

Cancer prehabilitation programs have been reported as effective ways to improve functional recovery, including functional walking capacity, reduced hospital stay after surgery, and lower morbidity and mortality rates from the primary treatment of cancer (Dunne et al., 2016; Gillis et al., 2014; Valkenet et al., 2011). Silver and Baima (2013) defined cancer prehabilitation as a process starting between cancer diagnosis and pretreatment, with interventions to decrease impairments and promote physical and psychological health along the cancer care continuum. Cancer prehabilitation programs have been studied in people with various forms of cancer, such as lung, colorectal, and breast, with findings showing that their use can decrease morbidity and readmissions and reduce healthcare costs in newly diagnosed patients (Mayo et al., 2011; Silver & Baima, 2013). Physical cancer prehabilitation programs typically consist of aerobic or resistance exercises, or a combination of both; such programs have been shown to improve exercise tolerance, QOL, and muscle strength (Dunne et al., 2016; Gillis et al., 2014; Silver & Baima, 2013). Physical cancer prehabilitation programs are often followed by psychological programs (Silver & Baima, 2013). Psychological cancer prehabilitation programs were shown to improve mood disturbance prior to treatment. In addition, people with cancer who participated in psychological cancer prehabilitation programs had better adaptation to daily life after discharge (Silver & Baima, 2013). Overall, patient participation in cancer prehabilitation programs can lead to improved preoperative conditions and better recovery status after surgery. However, because the components of cancer prehabilitation programs vary, the outcomes may also be mixed (Hijazi, Gondal, & Aziz, 2017).

QOL is correlated with survival in people with cancer because it includes various areas of well-being and considers the impact of the disease and its treatment (Jitender, Mahajan, Rathore, & Choudhary, 2018). People with cancer reported better QOL when they had a strong ability to cope with cancer and cancer-related treatment (Jitender et al., 2018).

A study by Silver and Baima (2013) demonstrated that prehabilitation programs have been shown to improve QOL for as many as six months after elective coronary bypass graft surgery, but similar research has yet to be conducted involving cancer prehabilitation programs among people with cancer. In addition, although Silver and Baima’s (2013) review was the first to examine cancer prehabilitation programs, the standardized steps of systematic review were not used to make conclusions, and the results were based on people with and without cancer. As a result, the connection between cancer prehabilitation programs and QOL remains unclear. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of the effect of cancer prehabilitation programs on QOL in people with cancer, with the hope that the results provide concrete recommendations to clinical care and nursing research that will enhance the quality of cancer prehabilitation. Two research questions were examined:

• What are the characteristics of cancer prehabilitation programs that lead to improved QOL in people with cancer?

• What are the effects of cancer prehabilitation programs on QOL?

Methods

This systematic review was guided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009), and it was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017070736). All included studies were randomized, controlled trials that examined the effects of cancer prehabilitation programs on QOL among people with cancer. Because few studies related to cancer prehabilitation programs have been conducted, the authors did not restrict the dates of publication during the database search process.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

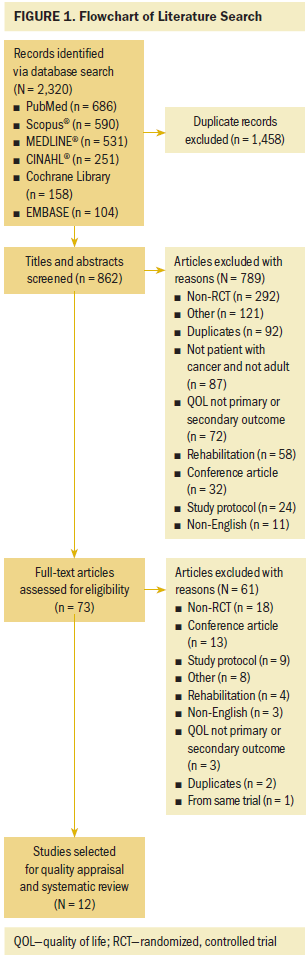

Various electronic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE®, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CINAHL®, Scopus®) were searched. Cancer prehabilitation has been described in a variety of ways (Silver & Baima, 2013); therefore, the following keywords related to cancer prehabilitation were used for the current study: prehabilitation, prehab, prophylactic rehabilitation, pretreatment rehabilitation, perioperative rehabilitation, preoperative exercise, preoperative rehabilitation, preoperative program, and perioperative program. Cancer and QOL, along with their synonyms, including neoplasms, carcinoma, tumor, and health-related QOL, were also used. All keywords were connected by Boolean operators without the limitation of year of publication. EndNote software was used as a reference management tool to screen duplicate publications. All studies were selected by the first and second authors. The titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed, and the full-text articles were then reviewed to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Any disagreements between the first and the second authors related to abstracted data were referred to the third author to reach consensus.

Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale (Yamato, Maher, Koes, & Moseley, 2017) was used to assess the quality of studies. The following items were examined for each study:

• Inclusion criteria and source of participants

• Random allocation of participants

• Concealment of allocation

• Baseline comparability

• Blinding of participants

• Blinding of those who administered the interventions

• Blinding of assessors

• Participant follow-up of more than 85%

• Intention-to-treat analysis (all patients who were randomized are included in the data analysis and are analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized)

• Between-group comparison

• Point measures and measures of variability for outcomes

Inclusion criteria and source were not used for calculation of the total PEDro score; this item relates more to external validity. Consequently, total PEDro scores ranged from 0–10 points, with higher scores indicating higher study quality. The current authors contacted the authors of each of the studies to obtain additional information. A unified form was used to extract data from 12 studies. The collected information included first author; year of publication; country; sample size; mean age, cancer type and stage of participants; and research setting.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Randomized, controlled trials in people with cancer aged at least 18 years and with people with cancer who participated in prehabilitation programs in the intervention groups were selected for inclusion. Articles in which QOL was not the primary or secondary outcome and which were not written in English were not eligible for this review.

Results

The search strategy initially found 2,320 articles across six databases; these had been published from 1968 to January 2018. Of these, 1,458 articles were identified as duplicates and removed. The titles, abstracts, and full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed in two phases, with 862 and 73 articles, respectively, excluded. Finally, 12 studies were selected for quality appraisal and systematic review.

Study Characteristics

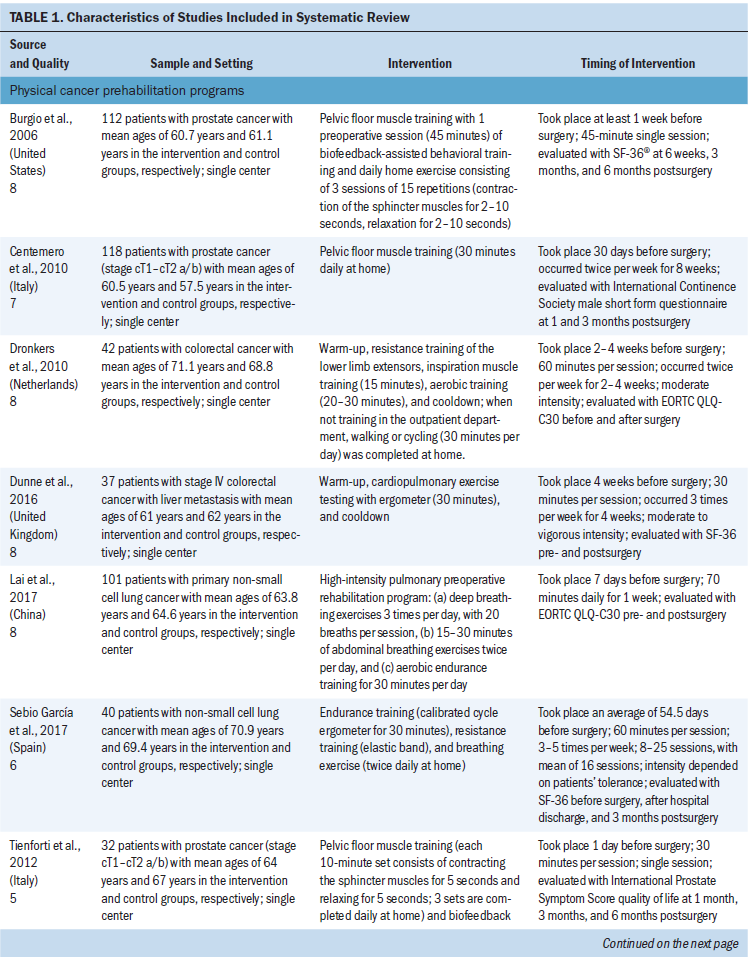

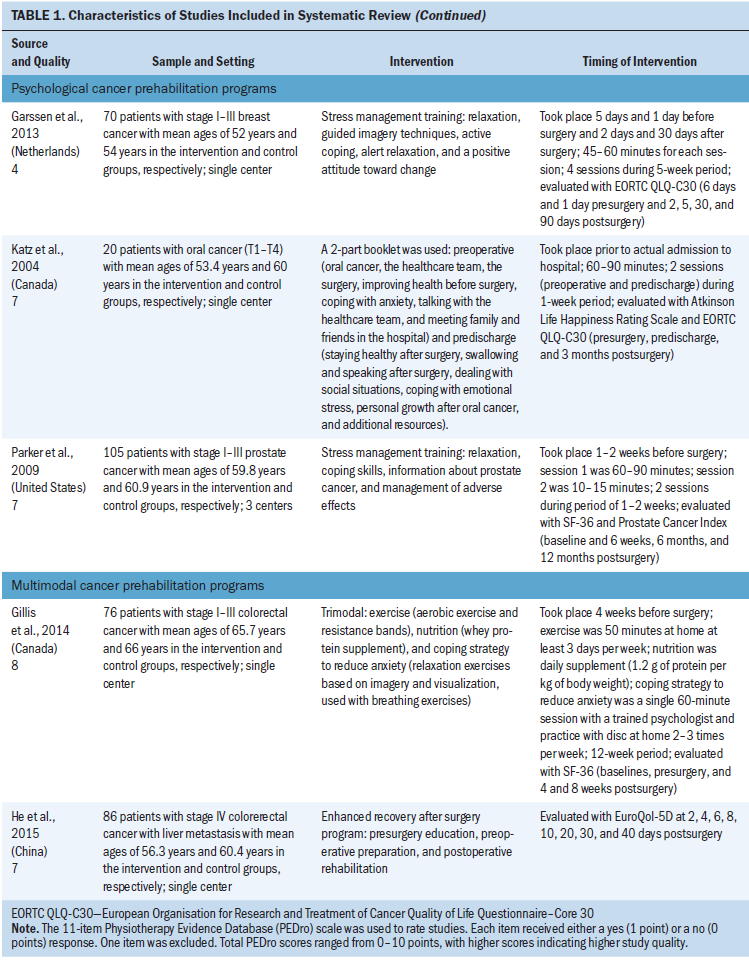

Study characteristics are provided in Table 1. Most studies were conducted in a single center. More than half of the studies were published during a five-year period and were conducted in Western countries (the United States, Italy, the Netherlands, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Spain). In addition, most of the studies had recruited people with prostate cancer (n = 4) or colorectal cancer (n = 3). The total sample size was 839 people with cancer (426 people participating in cancer prehabilitation programs and 413 people in the control groups). Mean age in the 12 studies ranged from 52–71 years.

Total scores of study quality, determined using the PEDro scale, ranged from 4–8, with most studies scoring 7 or 8; this implies that these studies were of fairly high quality. The weakest items were related to allocation of concealment and blinding.

A total of seven QOL instruments were used in the 12 studies, with the SF-36® or the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Questionnaire–Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) used in nine studies. (Instruments also used were the International Continence Society male short form questionnaire, International Prostate Symptom Score quality of life, Atkinson Life Happiness Rating Scale, Prostate Cancer Index, and EuroQol-5D.) The timing of the QOL outcome assessments varied, ranging from the day before surgery to 12 months after surgery.

Prehabilitation Program Characteristics

Physical cancer prehabilitation programs: Seven studies involved physical cancer prehabilitation programs in people with prostate, colorectal, and lung cancers (Burgio et al., 2006; Centemero et al., 2010; Dronkers et al., 2010; Dunne et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2017; Sebio García et al., 2017; Tienforti et al., 2012). The goal of the programs was to improve patients’ cardiopulmonary function (Dronkers et al., 2010; Dunne et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2017; Sebio García et al., 2017) or pelvic floor muscle function (Burgio et al., 2006; Centemero et al., 2010; Tienforti et al., 2012) through exercise.

One of the cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on cardiopulmonary function trained people with cancer using an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer for 30 minutes three times a week for four weeks; significantly improved QOL was noted in the intervention group, but no significant difference was found between groups (Dunne et al., 2016). Another study of a prehabilitation program aimed at improving cardiopulmonary function was comprised of endurance training, resistance training, and breathing exercises; the program was completed during 16 one-hour sessions and took place an average of 54.5 days before surgery (Sebio García et al., 2017). Overall, it showed that cancer prehabilitation programs focused on cardiopulmonary function can significantly improve the physical component summary scores of the SF-36 at three months postsurgery; this was noted in the intervention and control groups.

Regarding improvements to pelvic floor muscle function, only one study on a cancer prehabilitation program conducted 30 days before surgery showed any differences between the intervention and control groups (Centemero et al., 2010). In this study, the intervention took place during an eight-week period; the 30-minute intervention occurred twice per week.

Psychological cancer prehabilitation programs: The three studies that examined psychological cancer prehabilitation programs involved different types of cancer (breast, oral, and prostate) (Garssen et al., 2013; Katz, Irish, & Devins, 2004; Parker et al., 2009). Two of these studies were conducted using stress management techniques, including relaxation, guided imagery, and promotion of active coping and a positive attitude (Garssen et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2009). The other study used a psychoeducational program that provided information about oral cancer and its treatment, along with effective coping strategies (Katz et al., 2004). However, only the study by Garssen et al. (2013) demonstrated effectiveness of the program in improving QOL in the intervention group. This program consisted of four sessions (two prior to surgery and two after surgery) during a five-week period; each session was about 45–60 minutes in length.

Multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs: Of the two multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs, one was an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program comprising the presurgery, preoperative preparation, and postoperative rehabilitation periods (He, Lin, Xie, Huang, & Yuan, 2015), whereas the other was a trimodal program containing exercise, nutrition with whey protein supplement, and coping strategy training for anxiety reduction (Gillis et al., 2014). However, no differences were observed between the intervention and control groups in these studies.

Discussion

Unimodal and Multimodal Programs

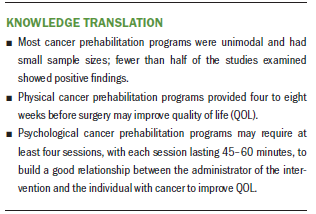

This is the first systematic review of cancer prehabilitation programs’ effects on QOL in people with cancer. Most studies examined interventions within unimodal cancer prehabilitation programs. Cancer prehabilitation programs that focused on improving cardiopulmonary function through exercise (n = 4), improving pelvic floor muscle function (n = 3), and providing stress management training (n = 2) were most prevalent. The studies involved people with various types of cancer, but the most common cancer types were prostate and colorectal. Only four studies (two focusing on improving cardiopulmonary function, one focusing on improving pelvic floor muscle function, and one focusing on providing stress management training) showed any differences between the intervention and control groups; these studies provided the intervention at four to eight weeks prior to surgery.

The results of the multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs examined in this review are not consistent with the previous review conducted by Silver and Baima (2013). Although Silver and Baima (2013) suggested that multimodal prehabilitation programs incorporating physical and psychological interventions may be more effective than unimodal prehabilitation programs (this was proven in diverse populations of people without cancer), evidence is lacking because they did not implement the standardized steps of systematic review. In addition, most of the studies discussed by Silver and Baima (2013) involved unimodal prehabilitation programs; consequently, their conclusions need further verification. Multimodal prehabilitation programs also were developed later than unimodal programs (Silver & Baima, 2013); as a result, the number of multimodal prehabilitation programs is smaller. Additional study on multimodal prehabilitation programs’ effects on QOL is needed.

Quality of Life

QOL was the primary (Burgio et al., 2006; Centemero et al., 2010; He et al., 2015; Katz et al., 2004; Tienforti et al., 2012) or secondary (Dunne et al., 2016; Garssen et al., 2013; Gillis et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2009; Sebio García et al., 2017) outcome in 10 studies included in this review. In addition, the SF-36 and the EORTC QLQ-C30 were used to measure the QOL of people with cancer in nine studies (Burgio et al., 2006; Dronkers et al., 2010; Dunne et al., 2016; Garssen et al., 2013; Gillis et al., 2014; Katz et al., 2004; Lai et al., 2017; Parker et al., 2009; Sebio García et al., 2017), but the time points for measurement varied. The SF-36 measures QOL during the past month (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992), whereas the EORTC QLQ-C30 measures QOL during the past seven days (Aaronson et al., 1993). The studies that employed these instruments did not point out the specific measurement time point of pre- or postsurgery. People with cancer usually experience different kinds of physical and mental symptoms, or varying levels of severity, at seven days, one month, or six months after surgery (Chen et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2012). Studies have shown that the worst physical function and QOL were reported by people with breast cancer in the first month after cancer-related treatment and that their QOL had not recovered at three months after cancer-related treatment (Cheng et al., 2012). Choosing an appropriate instrument to measure QOL and relevant time points for measurement pre- and postsurgery should be considered when cancer prehabilitation program studies are designed.

In the studies selected for inclusion in this review, the QOL instruments used were comprised of various domains (Jitender et al., 2018). For example, the SF-36 consists of eight subscales (i.e., physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health), and these can be divided into the physical and psychological domains of QOL. However, results reported by studies varied (e.g., the scores of two summarized domains, the scores of the eight subscales but without the two summarized domains) (Burgio et al., 2006; Dunne et al., 2016; Gillis et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2009; Sebio García et al., 2017). Consequently, the results were difficult to compare and analyze. A similar situation occurred with the EORTC QLQ-C30.

Physical cancer prehabilitation programs: Two types of physical cancer prehabilitation programs were examined in this review: cardiopulmonary exercise (n = 4) and pelvic floor muscle training (n = 3). In addition, just three studies showed that physical cancer prehabilitation programs could improve QOL in people with cancer (Centemero et al., 2010; Dunne et al., 2016; Sebio García et al., 2017).

Of the cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on cardiopulmonary function, two demonstrated improvements in QOL. However, the results were varied. In the cancer prehabilitation program using a cycle ergometer, significant improvement in QOL was noted only in the intervention group (Dunne et al., 2016). In the cancer prehabilitation program focusing on endurance training, resistance training, and breathing exercises, significant differences were found only in the physical component summary scores of the SF-36 between the intervention and control groups (Sebio García et al., 2017).

Variance in results could be attributed to the small sample size of the studies with physical cancer prehabilitation programs, ranging from 37–118 and with small effect size (0.04–0.27) (Burgio et al., 2006; Centemero et al., 2010; Dronkers et al., 2010; Dunne et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2017; Sebio García et al., 2017; Tienforti et al., 2012). Two studies in which the mean effect size was 0.11 did not show significant QOL differences within or between the intervention and control groups (Dronkers et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2017), and two studies in which the mean effect size was 0.2 showed significantly different results between the intervention and control groups (Dunne et al., 2016; Sebio García et al., 2017). Consequently, future research on physical cancer prehabilitation programs needs to feature larger sample sizes to further examine the effects of interventions.

In addition, within the physical cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on cardiopulmonary function that were examined in this review, the intensity of the training program played a significant role (Scharhag-Rosenberger et al., 2015). The American Cancer Society (2017) and the American College of Sports Medicine (Schmitz et al., 2010) recommend that people with cancer perform at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity exercise per week, which can increase cardiopulmonary function. However, only two of the studies (Dronkers et al., 2010; Dunne et al., 2016) with physical cancer prehabilitation programs examined in this review indicated that the exercise intensity was at a moderate or a moderate to vigorous level. This exercise intensity signifies a 55%–75% maximal heart rate (Dronkers et al., 2010) or less than 60% to more than 90% oxygen uptake (Dunne et al., 2016). However, these studies did not note how the intensity level was measured or whether the participants reached the intended intensity of the training program when participating in the intervention. Participants in the Dronkers et al. (2010) study were to walk or cycle 30 minutes per day at home, but the intensity of this exercise was not measured at home and compliance was not reported. Although compliance monitoring may be difficult, compliance is an important factor influencing the results of an intervention and should be carefully monitored (Gearing et al., 2011).

Among cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on pelvic floor muscle training, only one study (Centemero et al., 2010) showed significantly improved QOL in people with prostate cancer; the 30-minute intervention in this study was provided twice weekly in the eight weeks prior to surgery. In other studies with programs focusing on pelvic floor muscle training, the intervention consisted of a single session of 30–45 minutes offered seven days prior to surgery; improved QOL was not noted, which calls into question the effectiveness of a single intervention session (Burgio et al., 2006; Tienforti et al., 2012).

Studies have shown that people with prostate cancer have lower levels of anxiety, depression, and social inhibition and increased QOL with improvements in urinary continence (Zhang, Strauss, & Siminoff, 2006). Pelvic floor muscle training is considered to be the first-line treatment for urinary incontinence (Newman & Wein, 2013). In studies in which pelvic floor muscle training programs demonstrated significant improvements to urinary continence, interventions were conducted at least twice (Filocamo et al., 2005; Sueppel, Kreder, & See, 2001; Van Kampen et al., 2000). The two studies in which the results did not show improved QOL (Burgio et al., 2006; Tienforti et al., 2012) incorporated only a single session.

A significant outcome of interventions focusing on pelvic floor muscle training is whether people with cancer can correctly identify the pelvic muscles to perform the exercises. Newman and Wein (2013) suggested that researchers should check with participants to determine if the correct muscles are being used after the first training session. Accordingly, having at least two intervention sessions can help researchers verify whether the exercises are being correctly performed prior to surgery. One recommendation for physical cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on pelvic floor muscle training is to devote the first session to teaching the exercises to participants and the second and additional sessions to determining whether participants are correctly performing the exercises.

All studies centered on cancer prehabilitation programs with pelvic floor muscle training interventions asked participants to practice these exercises daily at home. However, the frequency of this practice is important to consider. Newman and Wein (2013) suggested that people with cancer should perform at least 45–60 pelvic floor muscle exercises per day.

Urinary incontinence is the most common complication after surgery in people with prostate cancer, and it may cause anxiety, depression, and social inhibition, which can affect an individual’s psychological and social QOL (Parekh et al., 2003). The severity and duration of urinary incontinence also affects QOL and should be considered in the intervention (Parekh et al., 2003). Two studies (Centemero et al., 2010; Tienforti et al., 2012) examined in this review used specific QOL instruments in people with cancer (International Continence Society male short form questionnaire in the former study, International Prostate Symptom Score quality of life in the latter study). Choosing specific instruments to assess participants’ QOL should be considered in the research design process.

Psychological cancer prehabilitation programs: For this review, two studies (Garssen et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2009) were examined that looked at psychological cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on stress management training in people with early-stage breast or prostate cancer. However, just the study by Garssen et al. (2013) demonstrated improvement in overall QOL. These studies varied in terms of content and intervention dose. In the Garssen et al. (2013) study, the intervention was administered prior to surgery (5 days before and 1 day before) and after surgery (2 days after and 30 days after); the intervention was also given for a total of 180–240 minutes during five weeks, compared to 70–105 minutes in one to two weeks in the Parker et al. (2009) study.

Rehse and Pukrop (2003), who conducted a review concerning the effects of a psychosocial intervention on QOL in people with cancer, found that at least 12 weekly intervention sessions are needed to improve QOL in people with cancer; they attributed this need to the significance of the relationship between the psychologist and the person with cancer, particularly the stability and level of trust established, in psychosocial interventions. Psychological cancer prehabilitation programs may need at least four intervention sessions, with each session lasting 45–60 minutes, to improve the effect of the intervention on QOL (Rehse & Pukrop, 2003).

Trained psychologists play an important role in guiding people with cancer in psychological cancer prehabilitation programs (Gearing et al., 2011), but two studies (Garssen et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2009) focusing on stress management training stated only that the interventions were conducted by a clinical psychologist and did not provide any details about his or her professional experience. Adequate training and management of those who administer interventions are necessary, particularly for social, psychological, and behavioral interventions (Gearing et al., 2011). The effect size of the Garssen et al. (2013) study was 0.29–0.32 among four QOL measurement time points (days 2, 5, 30, and 90 postsurgery), which is consistent with the effect size of 0.31 in the Rehse and Pukrop (2003) study.

Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations, and the results should be interpreted with caution. For example, most of the treatment allocation was not concealed, and blinding was not performed. Although it was not possible to blind participants to the intervention, the data collectors should have been blinded for better quality assurance during data collection. In addition, although this review included a greater number of randomized, controlled trials than previous systematic reviews of cancer prehabilitation programs, the number of studies was still relatively small. Therefore, meta-analysis could not be conducted. Finally, multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs have been noted in various reviews (Looijaard, Slee-Valentijn, Otten, & Maier, 2017; Loughney & Grocott, 2016), but only two studies examining multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs were selected for this review. Consequently, the effects of multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs on QOL could not be fully studied in this review.

Implications for Nursing

In this review, the authors found that physical cancer prehabilitation programs provided four to eight weeks before surgery and psychological cancer prehabilitation programs consisting of four sessions, each lasting 45–60 minutes, during a five-week period may improve QOL. Cancer prehabilitation programs may be a useful way to promote QOL during the continuous process of cancer care. Oncology nurses could provide various interventions to patients who decide to undergo surgery. In terms of physical care, nurses could recommend that people with cancer perform cardiopulmonary exercise of a moderate to vigorous intensity (e.g., electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer, resistance training) for 30–60 minutes three to five times each week, depending on their tolerance; this exercise should begin sometime between cancer diagnosis and pretreatment. In terms of psychological care, oncology nurses could teach stress management skills (e.g., deep breathing, strategies for coping with anxiety, relaxation techniques) to help decrease patients’ stress related to cancer or its treatment.

In addition, nurse researchers should make sure that the QOL instruments used are specific and relate to the content of the cancer prehabilitation program, the cancer type, and the time points for evaluation. Having a large sample size or an effect size of 0.2 should also be considered, as should ensuring adequate duration of the intervention (i.e., at least 12 weekly sessions). The intensity, duration, and total sessions of the intervention should be reported in the corresponding study. Intervention fidelity and compliance should be considered. In addition, comparing and contrasting the effects of unimodal and multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs on QOL is needed.

Conclusion

Physical cancer prehabilitation programs provided at least four weeks before surgery may improve QOL in people with cancer, and psychological cancer prehabilitation programs focusing on stress management and consisting of at least four sessions of 45–60 minutes each has been shown to improve QOL after surgery. This review found that most studies had been conducted with unimodal physical cancer prehabilitation programs and that, overall, the studies that have been done of cancer prehabilitation programs are varied in terms of study design. In the future, researchers should work to design studies that employ proper instruments, large sample size, strong relationship building between those who administer the interventions and those who take part in it, and compliance monitoring of patients. High-quality randomized, controlled trials with large sample sizes looking at multimodal cancer prehabilitation programs are required to demonstrate the benefits of cancer prehabilitation programs on QOL in people with cancer.

About the Author(s)

Yun-Jen Chou, RN, MSN, is a doctoral student, Hsuan-Ju Kuo, RN, MSN, is a research assistant, and Shiow-Ching Shun, RN, PhD, is a professor, all in the School of Nursing in the College of Medicine at National Taiwan University in Taipei. No financial relationships to disclose. Chou and Shun contributed to the conceptualization and design and provided statistical support. All authors completed the data collection, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Shun can be reached at scshun@ntu.edu.tw, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2018. Accepted June 6, 2018.)

References

Aaronson, N.K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N.J., . . . de Haes, J.C. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85, 365–376.

American Cancer Society. (2017). ACS guidelines for nutrition and physical activity. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/healthy/eat-healthy-get-active/acs-guidelines-nu…

Astrup, G.L., Rustøen, T., Hofsø, K., Gran, J.M., & Bjordal, K. (2017). Symptom burden and patient characteristics: Association with quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Head and Neck, 39, 2114–2126. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24875

Burgio, K.L., Goode, P.S., Urban, D.A., Umlauf, M.G., Locher, J.L., Bueschen, A., & Redden, D.T. (2006). Preoperative biofeedback assisted behavioral training to decrease post-prostatectomy incontinence: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Urology, 175, 196–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00047-9

Centemero, A., Rigatti, L., Giraudo, D., Lazzeri, M., Lughezzani, G., Zugna, D., . . . Guazzoni, G. (2010). Preoperative pelvic floor muscle exercise for early continence after radiacal prostatectomy: A randomised controlled study. European Urology, 57, 1039–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2010.02.028

Chen, Y.-H., Liang, W.-A., Hsu, C.-Y., Guo, S.-L., Lien, S.-H., Tseng, H.-J., & Chao, Y.-H. (2018). Functional outcomes and quality of life after a 6-month early intervention program for oral cancer survivors: A single-arm clinical trial. PeerJ, 6, e4419. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4419

Cheng, S.-Y., Lai, Y.-H., Chen, S.-C., Shun, S.-C., Liao, Y.-M., Tu, S.-H., . . . Chen, C.-M. (2012). Changes in quality of life among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03735.x

Dronkers, J.J., Lamberts, H., Reutelingsperger, I.M., Naber, R.H., Dronkers-Landman, C.M., Veldman, A., & van Meeteren, N.L. (2010). Preoperative therapeutic programme for elderly patients scheduled for elective abdominal oncological surgery: A randomized controlled pilot study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 24, 614–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509358941

Dunne, D.F., Jack, S., Jones, R.P., Jones, L., Lythgoe, D.T., Malik, H.Z., . . . Fenwick, S.W. (2016). Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation before planned liver resection. British Journal of Surgery, 103, 504–512. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10096

Filocamo, M.T., Li Marzi, V., Del Popolo, G., Cecconi, F., Marzocco, M., Tosto, A., & Nicita, G. (2005). Effectiveness of early pelvic floor rehabilitation treatment for post-prostatectomy incontinence. European Urology, 48, 734–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2005.06.004

Garssen, B., Boomsma, M.F., de Jager Meezenbroek, E., Porsild, T., Berkhof, J., Berbee, M., . . . Beelen, R.H. (2013). Stress management training for breast cancer surgery patients. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 572–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3034

Gearing, R.E., El-Bassel, N., Ghesquiere, A., Baldwin, S., Gillies, J., & Ngeow, E. (2011). Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.007

Gillis, C., Li, C., Lee, L., Awasthi, R., Augustin, B., Gamsa, A., . . . Carli, F. (2014). Prehabilitation versus rehabilitation: A randomized control trial in patients undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Anesthesiology, 121, 937–947. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000000393

Große, J., Treml, J., & Kersting, A. (2018). Impact of caregiver burden on mental health in bereaved caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4529

He, F., Lin, X., Xie, F., Huang, Y., & Yuan, R. (2015). The effect of enhanced recovery program for patients undergoing partial laparoscopic hepatectomy of liver cancer. Clinical and Translational Oncology, 17, 694–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-015-1296-9

Hijazi, Y., Gondal, U., & Aziz, O. (2017). A systematic review of prehabilitation programs in abdominal cancer surgery. International Journal of Surgery, 39, 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.111

Jitender, S., Mahajan, R., Rathore, V., & Choudhary, R. (2018). Quality of life of cancer patients. Journal of Experimental Therapeutics and Oncology, 12, 217–221.

Katz, M.R., Irish, J.C., & Devins, G.M. (2004). Development and pilot testing of a psychoeducational intervention for oral cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 13, 642–653. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.767

Lai, Y., Su, J., Qiu, P., Wang, M., Zhou, K., Tang, Y., & Che, G. (2017). Systematic short-term pulmonary rehabilitation before lung cancer lobectomy: A randomized trial. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, 25, 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivx141

Looijaard, S.M., Slee-Valentijn, M.S., Otten, R.H., & Maier, A.B. (2017). Physical and nutritional prehabilitation in older patients with colorectal carcinoma: A systematic review. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1519/jpt.0000000000000125

Loughney, L., & Grocott, M.P. (2016). Exercise and nutrition prehabilitation for the evaluation of risk and therapeutic potential in cancer patients: A review. International Anesthesiology Clinics, 54(4), e47–e61. https://doi.org/10.1097/aia.0000000000000122

Mayo, N.E., Feldman, L., Scott, S., Zavorsky, G., Kim, D.J., Charlebois, P., . . . Carli, F. (2011). Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: Argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery, 150, 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.045

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1006–1012.

Newman, D.K., & Wein, A.J. (2013). Office-based behavioral therapy for management of incontinence and other pelvic disorders. Urologic Clinics of North America, 40, 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2013.07.010

Parekh, A.R., Feng, M.I., Kirages, D., Bremner, H., Kaswick, J., & Aboseif, S. (2003). The role of pelvic floor exercises on post-prostatectomy incontinence. Journal of Urology, 170, 130–133. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000072900.82131.6f

Parker, P.A., Pettaway, C.A., Babaian, R.J., Pisters, L.L., Miles, B., Fortier, A., . . . Cohen, L. (2009). The effects of a presurgical stress management intervention for men with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 3169–3176. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.16.0036

Rehse, B., & Pukrop, R. (2003). Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: Meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 50, 179–186.

Scharhag-Rosenberger, F., Kuehl, R., Klassen, O., Schommer, K., Schmidt, M.E., Ulrich, C.M., . . . Steindorf, K. (2015). Exercise training intensity prescription in breast cancer survivors: Validity of current practice and specific recommendations. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 9, 612–619.

Schmitz, K.H., Courneya, K.S., Matthews, C., Demark-Wahnefried, W., Galvão, D.A., Pinto, B.M., . . . Schwartz, A.L. (2010). American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42, 1409–1426.

Sebio García, R., Yáñez-Brage, M.I., Giménez Moolhuyzen, E., Salorio Riobo, M., Lista Paz, A., & Borro Mate, J.M. (2017). Preoperative exercise training prevents functional decline after lung resection surgery: A randomized, single-blind controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 31, 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215516684179

Silver, J.K., & Baima, J. (2013). Cancer prehabilitation: An opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92, 715–727. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31829b4afe

Sueppel, C., Kreder, K., & See, W. (2001). Improved continence outcomes with preoperative pelvic floor muscle strengthening exercises. Urologic Nursing, 21, 201–210.

Tienforti, D., Sacco, E., Marangi, F., D’Addessi, A., Racioppi, M., Gulino, G., . . . Bassi, P. (2012). Efficacy of an assisted low-intensity programme of perioperative pelvic floor muscle training in improving the recovery of continence after radical prostatectomy: A randomized controlled trial. BJU International, 110, 1004–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10948.x

Valkenet, K., van de Port, I.G., Dronkers, J.J., de Vries, W.R., Lindeman, E., & Backx, F.J. (2011). The effects of preoperative exercise therapy on postoperative outcome: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25, 99–111.

Van Kampen, M., de Weerdt, W., Van Poppel, H., De Ridder, D., Feys, H., & Baert, L. (2000). Effect of pelvic-floor re-education on duration and degree of incontinence after radical prostatectomy: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 355, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03473-x

Ware, J.E., Jr., & Sherbourne, C.D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473–483.

World Health Organization. (2018). Cancer. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en

Yamato, T.P., Maher, C., Koes, B., & Moseley, A. (2017). The PEDro scale had acceptably high convergent validity, construct validity, and interrater reliability in evaluating methodological quality of pharmaceutical trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 86, 176–181.

Zhang, A.Y., Strauss, G.J., & Siminoff, L.A. (2006). Intervention of urinary incontinence and quality of life outcome in prostate cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24(2), 17–30.