Supporting Change in Oncology Nursing Practice in Kuwait

As countries around the world struggle to provide oncology care and treatment to their populations, nurses, as the largest healthcare workforce, are faced with the challenge of obtaining, maintaining, and developing specialized oncology nursing knowledge and expertise. Strategies that can be deployed at a local level to support nurses with integrating new knowledge into practice are important in meeting and overcoming this challenge. This article describes a theory-based model for implementing oncology nursing best practices in the Middle Eastern country of Kuwait.

Jump to a section

The Kuwait Ministry of Health (KMOH) entered into a five-year partnership with Canada’s University Health Network Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (UHN-PM) to develop oncology programs at the Kuwait Cancer Control Center (KCCC) that were adapted from UHN-PM service models. UHN-PM has accountability to provide clinical care services to its local community and, at the same time, act as a provincial and national resource for tertiary and quaternary services. Its mandate of global impact extends the responsibility to also act as an international resource. This has resulted in reaching out to several countries to share expertise.

The framework for UHN-PM’s partnership with KCCC focused on building a long‐term relationship with an organization that was striving to improve health care for their population, interested in building local capacity, and motivated to change by encompassing a strategy of knowledge transfer and capacity building. The approach was to partner rather than be prescriptive and to adapt programs rather than adopt them. KCCC and UHN-PM worked collaboratively to achieve their goals, focusing on international best oncology practice while developing locally generated solutions to difficult global problems.

KCCC was developed in the early 1970s as a tertiary healthcare center in the Sabah health region of Kuwait. It is the only oncology center in Kuwait providing comprehensive oncology services to adult patients with cancer, treating about 2,000 newly diagnosed cases per year. KCCC is comprised of five buildings with a 229-bed capacity and has roughly 1,650 medical, allied health, and administrative staff (KCCC, 2012). One goal of partnering with UHN-PM was to transform existing cancer services for the Kuwaiti population by increasing local capacity. This would enable more Kuwaiti citizens to receive care at home instead of going abroad for treatment. Nurses in Kuwait are not regulated by a health profession college, and the development of nursing knowledge within the country is predominantly at the baccalaureate level.

The partnership with KCCC used a three-pronged approach to enhance hospital services. First, experts from UHN-PM conducted focused site visits throughout the year. The site visitors were from all levels of the organization: frontline experts who modeled care delivery of UHN-PM in the Kuwait setting; departmental leadership collaborating with their KCCC counterparts in developing, executing, and monitoring improvement strategies; and executive leadership teams ensuring that the engagement was providing value to the Ministry of Health and setting future direction for cancer care at the systems level. The second prong was a UHN-PM multidisciplinary team based in Kuwait. This team worked with their KCCC partners daily to facilitate implementation of recommendations made by visiting experts and leadership teams and provided continuity in between visits. The local team also provided change management expertise and operational support to KCCC to help execute plans and monitor progress. The third prong consisted of ongoing remote collaboration between Kuwait and Toronto through videoconferencing education, joint case rounds, second opinion consultations, and training in Toronto.

Best Practice in Nursing Program and Implementation Strategies

Along with the KMOH and KCCC hospital administration, the KCCC and UHN-PM nursing departments also committed to making a significant contribution to cancer care in Kuwait by implementing strategies to develop specialized nursing knowledge, build expertise in oncology care, and provide leadership in evidence-based practice. One of the challenges encountered was having KCCC staff learn new knowledge and then apply it to their daily nursing practice. To enable this integration, a program was developed that sought to support the translation of knowledge into practice and reinforce the uptake of key practice changes.

Built on observations and feedback from Kuwaiti nursing staff, a Best Practice in Nursing (BPN) program was established. The program consisted of a monthly package designed to facilitate the consolidation of new knowledge. Each package was comprised of a poster in a question-and-answer format, a self-directed learning module, and an applicable case study and quiz. The development of this program was based on Pronovost’s model for translating evidence into practice (Pronovost, Berenholtz, & Needham, 2008; World Health Organization, 2010). The Pronovost model directs attention at the implementation phase to engage, educate, execute, and evaluate (i.e., the 4E framework). Engagement is intended to motivate key stakeholders to take ownership and support the proposed interventions, education ensures that the key stakeholders understand why the proposed interventions are important, execution embeds the intervention into standardized care processes, and evaluation helps determine whether the intervention was successful. The BPN materials were developed by the onsite UHN-PM educator in consultation with the KCCC nursing education team known as the staff development unit (SDU).

To clearly identify the program and have it easily accessible to staff, two initiatives were implemented. A bulletin board was placed on each unit and identified as the BPN bulletin board. This board was only used for the monthly poster and related practice materials. In addition, a visual identity was developed for the program so that visual clues would alert nurses to the program materials. Changing the color of the posters each month was determined to be helpful in alerting staff to a new topic and material. A resource package was also provided to nurse managers each month that offered ideas on how to use the BPN materials in the 4E framework to foster staff learning and clinical application.

Some topics covered in the BPN program included dysphagia, pleural effusion, tracheostomy care, chest tubes management, and breast cancer. The BPN’s monthly focus arose from topics that had been identified as needing further reinforcement, topics where a clinical controversy existed, or topics where a newly implemented practice change required additional support.

The Best Practice in Nursing Program in Action: Two Examples

Smoking cessation: A practice change that benefited from the BPN program was the KCCC and UHN-PM collaborative development and implementation of a nurse-led smoking cessation initiative. Before the smoking cessation initiative, no structured approach was in place for supporting smoking cessation for patients, although screening for tobacco use occurred at the physician and nursing levels. Various study results have indicated that minimal interventions can be effective when nurses provide patients with information about the potential benefits of smoking cessation and counseling (Rice & Stead, 2004). The implementation of the nurse-led smoking cessation initiative at KCCC promoted the identification of patients who smoke or were recent quitters and then provided consistent smoking cessation education, counseling, and resources to these patients on the trial units. Study results from the trial showed that the initiative was successful in assisting patients with cancer at KCCC to either quit smoking or to maintain a smoke-free lifestyle, thereby promoting improved patient outcomes, including the enhancement of quality of life and general health. The original study was piloted on four inpatient wards (two surgical oncology and two medical oncology) and, when successful, expanded to all inpatient and ambulatory areas. The initiative was a first for Kuwait, and the initiative’s purpose and implementation were highlighted and reinforced by the BPN program through a question-and-answer poster, a self-directed learning module, and a case study.

Hemolyzed blood samples: The BPN program also supported a nurse-led endeavor to reduce hemolyzed blood sample rates. A review of how nurses performed venipuncture identified three commonly used practices that are known to increase hemolysis rates: (a) not allowing the cleansing alcohol to dry, (b) using preexisting IV sites for the blood draw, and (c) delaying transportation of the sample to the blood laboratory (Lowe et al., 2008, Shah et al., 2009). Discussion with the nurses determined that most understood best practice, but implementation was a struggle because the nurses felt rushed and little time was available to implement best practice. To bring this issue forward and encourage further discussion at the clinical level, a BPN package was developed and distributed. The package included a question-of-the-month poster, a self-directed learning module, a case study, and a manager resource. The BPN question highlighted the nursing practices that were contributing to sample rejection followed by an explanation of best practice and its importance. In the months following this spotlight on venipuncture, a declining trend with the blood sample rejection rate was reported by the hospital’s laboratory.

Program Evaluation

Knowledge acquisition by nurses through the BPN education materials was assessed through voluntary completion of clinical case studies and quizzes. Nurses who completed the provided testing material and obtained a grade of 80% or better received a certificate of completion and one continuing education credit. Those who did not pass, which was rare, were provided additional support and education on the topic. In addition, staff who successfully completed the education material were entered into a monthly lottery for a gift certificate.

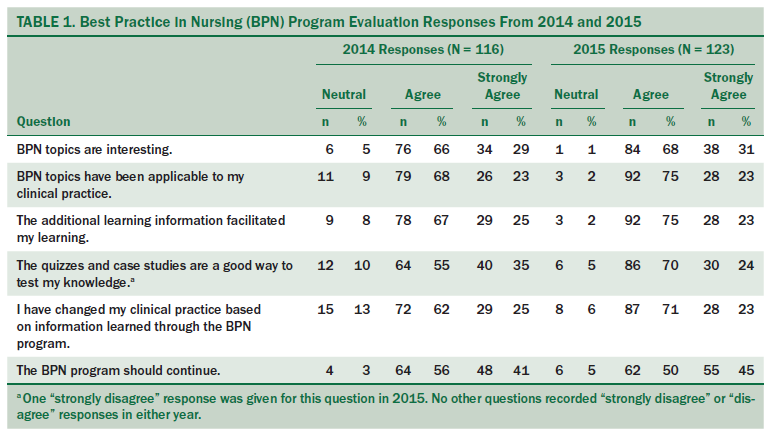

A baseline program evaluation was conducted across all clinical areas. A total of 159 evaluations were circulated and 116 were returned (a completion rate of 73%). The questionnaire consisted of eight questions. Six questions used a five-point Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and two used an open-ended response format. A second follow-up evaluation took place one year later with the questionnaires being circulated to the same areas of KCCC and a different group of nurse participants. The same sampling strategy was used, which resulted in a consistent return rate of 72%. Nurses rated the BPN extremely favorably (see Table 1).

Lessons Learned

Although the BPN program was well liked and successful with the Kuwaiti nursing staff, a considerable amount of time and energy was required for the program to occur on a monthly basis. Specifically, the UHN-PM educator overseeing the program had a short turnaround time to identify a practice issue, perform a literature search, and to develop the poster and all supporting materials. In addition, reviewing and providing feedback on completed cases studies, an important component to facilitate knowledge application to specific clinical scenarios, further added to the program’s workload. The considerable time needed for monthly program distribution became a hindering factor in the ongoing sustainability of the program during its transition from UHN-PM to the KCCC SDU. The transition period occurred during the fifth and final year of the contract and involved mentoring, education, and support of the SDU educators. During the transition, it became evident that monthly distribution was simply not a realistic goal given the SDU’s preexisting work commitments. The more reasonable goal of once per quarter program distribution was made, allowing for the initiative to continue without providing significant strain on the SDU staff.

Conclusion

The BPN program was effective in highlighting practice changes and clinical questions and bringing these forward for focused and consistent discussion by KCCC nursing staff. The supporting materials within the BPN program package provided opportunities for staff to further understand and integrate new knowledge into their practice. This approach has the potential to be effective in a variety of clinical programs and service areas. It provides a structured and theory-based method for embedding new or changed practices into daily care processes and can be customized to specific initiatives. The BPN program also promotes consistent care to patients by decreasing unnecessary variations in care practices through the integration and promotion of evidence-informed practice.

The success of the BPN program also highlights one way that two international nursing programs, working in partnership, achieved their goal of making a significant contribution to cancer care in Kuwait.

About the Author(s)

Nickerson was the director of clinical operations and Deering is a nurse practitioner, both at the University Health Network Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario; and Alazmei is the regional director of nursing in the Kuwait Cancer Control Center at the Ministry of Health of Kuwait in Shuwaikh. No financial relationships to disclose. Nickerson can be reached at nickerson_veronica@yahoo.ca, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org.

References

Kuwait Cancer Control Center. (2012). About us. Retrieved from http://www.kuwaitcancercenter.com/About-KCCC.php

Lowe, G., Stike, R., Pollack, M., Bosley, J., O’Brien, P., Hake, A., . . . Stover, T. (2008). Nursing blood specimen collection techniques and hemolysis rates in an emergency department: Analysis of venipuncture versus intravenous catheter collection techniques. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 34, 26–32.

Pronovost, P.J., Berenholtz, S.M., & Needham, D.M. (2008). Translating evidence into practice: A model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ, 337, a1714. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1714

Rice, V.H., & Stead, L.F. (2004). Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2004, CD001188. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub2

Shah, K.G., Idrovo, J.P., Nicastro, J., McMullen, H.F., Molmenti, E.P., & Coppa, G. (2009). A retrospective analysis of the incidence of hemolysis in type and screen specimens from trauma patients. International Journal of Angiology, 18, 182–183.

World Health Organization. (2010). Translating evidence to safer care. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/patientsafety/research/ps_online_course_session7_int…