Functional Quality-of-Life Outcomes Reported by Men Treated for Localized Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review

Problem Identification: To systematically evaluate the literature for functional quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes following treatment for localized prostate cancer.

Literature Search: The MEDLINE®, CINAHL®, EMBASE, British Nursing Index, PsycINFO®, and Web of Science™ databases were searched using key words and synonyms for localized prostate cancer treatments.

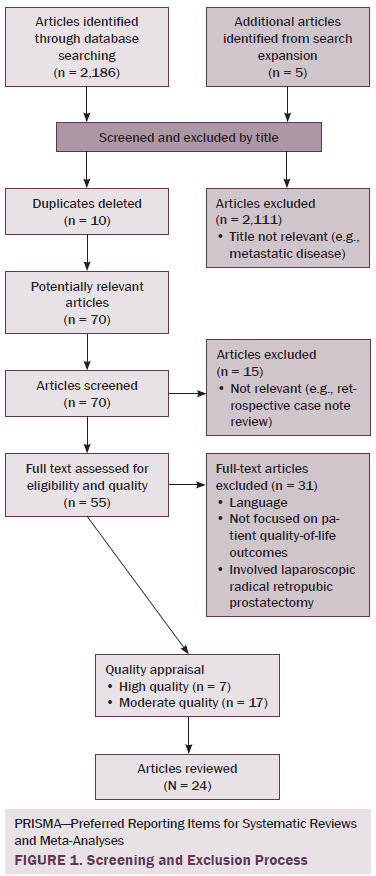

Data Evaluation: Of the 2,191 articles screened for relevance and quality, 24 articles were reviewed. Extracted data were tabulated by treatment type and sorted by dysfunction using a data-driven approach.

Synthesis: All treatments caused sexual dysfunction and urinary side effects. Radiation therapy caused bowel dysfunction, which could be long-term or resolved within a few years. Sexual function could take years to return. Urinary incontinence resolved within two years of surgery but worsened following radiation therapy. Fatigue was worse during treatment with adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy, and some men experienced post-treatment fatigue for several years.

Conclusions: This review identified that QOL outcomes reported by men following different treatments for localized prostate cancer are mostly recorded using standardized health-related QOL outcome measures. Such outcome measures collect data about body system functions but limit understanding of men’s QOL following treatment for prostate cancer. Holistic outcome measures are needed to capture data about men’s QOL for several years following the completion of treatment for localized prostate cancer.

Implications for Practice: Nurses need to work with men to facilitate information sharing, identify supportive care needs, and promote self-efficacy, and they should make referrals to specialist services, as appropriate.

Jump to a section

Prostate cancer is classified as localized in men with a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 10–20 ng/ml, a Gleason score of 7 or less, and a suspected prostate tumor stage of T1–T2c on digital rectal examination (European Association of Urology [EAU], 2015). Primary outcomes of different treatments for localized prostate cancer are equivocal; consequently, in England and Wales, a standard protocol for “best treatment” does not exist (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2014). Men with low- and intermediate-risk localized prostate cancer are offered one of several treatment modalities, including active surveillance, radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP), external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), and brachytherapy. Men with high-risk localized prostate cancer are offered radical surgery or radiation therapy but not active surveillance (NICE, 2014). Men with intermediate- and high-risk localized prostate cancer may also be offered androgen-deprivation therapy as an adjuvant to radiation therapy to maximize treatment efficacy (Shelley et al., 2009). Adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy may be given neoadjuvantly, six months prior to radiation therapy, or six months to three years following radiation therapy (NICE, 2014).

NICE (2014) and the EAU (2015) have recommended that men with a 10-year life expectancy and who are potent at the time of diagnosis be offered nerve-sparing surgery to treat their localized prostate cancer. Minimally invasive surgical procedures, such as laparoscopic prostatectomy and robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy, have begun to replace open surgical techniques (EAU, 2015; Gandaglia et al., 2014; Ramsay et al., 2012). In addition, focal therapy treatments (e.g., cryotherapy, ablation, low-energy radiofrequency) are being evaluated in clinical trials (Valerio et al., 2014).

A systematic search of relevant databases identified a few reviews reporting outcomes following treatment for localized prostate cancer. However, none were systematic reviews that reported data about quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes that had been collected from men receiving surgical or radiation treatment for localized prostate cancer (Kendirci, Bejma, & Hellstrom, 2006; Nilsson, Norlén, & Widmark, 2004; Pagliarulo et al., 2012). A health technology assessment investigating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of robotic prostatectomy (Ramsay et al., 2012) found that no evidence exists to conclude better cancer-related, patient-driven, or erectile dysfunction outcomes from robotic surgery compared to other surgical prostatectomy techniques. Primary research studies have reported several side effects associated with localized treatment for prostate cancer, some of which may last several years (Resnick et al., 2013; Soderdahl et al., 2005).

The treatment decision-making process must include consideration of QOL outcomes associated with side effects during and following treatment. Therefore, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify QOL outcomes reported by men after receiving surgery or radiation therapy with or without androgen-deprivation therapy for localized prostate cancer to determine if the severity and duration of impaired QOL differed between treatments.

Methods

Literature Search

A systematic search of the literature was carried out. Using Boolean operators, medical subject headings (MeSH) for cancer, prostate, surgery, radiotherapy, quality of life, incontinence, and side effects were used to search the MEDLINE®, CINAHL®, EMBASE, British Nursing Index, and PsycINFO® databases. The authors restricted the publication language to English, and no date limitation was used. Systematic searches of databases carried out in July 2011 have since been repeated, with the most recent search conducted in August 2014 to ensure that search results were up-to-date. The search was expanded by snowballing reference lists of articles included in the review and citation chaining using Web of Science™.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Because of increased survival from improved treatment outcomes, assessment and management of QOL is paramount for providing optimal health care. QOL is a multidimensional concept that includes health, social, and mental domains (WHOQOL Group, 1998).

Numerous QOL measures are used in prostate cancer studies, such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) (McKenzie & van der Pol, 2009), the International Prostate System Score (IPSS) (Barry et al., 1992), and the SF-36® (Ware & Gande, 1994). QOL outcomes are also reported from qualitative research studies. To capture the breadth of research reporting QOL in men treated for localized prostate cancer, articles that reported primary data collected directly from men on the effects on QOL following radical prostatectomy, or following EBRT or brachytherapy with or without adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy, for localized prostate cancer were included in the review. Articles were included in the review only if QOL outcomes could be assigned to a specific treatment type. Articles that did not present data on QOL outcomes collected from men (e.g., from healthcare providers, from retrospective studies of case notes) were excluded. Articles that collected data on treatment of men with locally spread or metastatic disease were also excluded.

Appraisal and Exclusion Process

All articles were reviewed by the primary author. Articles with potentially relevant titles that did not include an abstract were obtained in full text. A deterministic sample of every fourth study was independently reviewed for exclusion decision by a second reviewer. All articles that had possibly relevant content were retrieved in full text to assess for inclusion. Exclusion of articles retrieved in full text were discussed and agreed on by the researchers.

The quality of articles was assessed using Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools that were relevant for the research design being appraised (Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis, & Dillon, 2003). Quality assessment and exclusion decisions of full-text articles were conducted by two independent researchers. Articles that achieved a CASP score of 8 out of 12 or greater were included in the review. The exclusion process is summarized using an adapted PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) (see Figure 1).

Data Extraction and Analysis

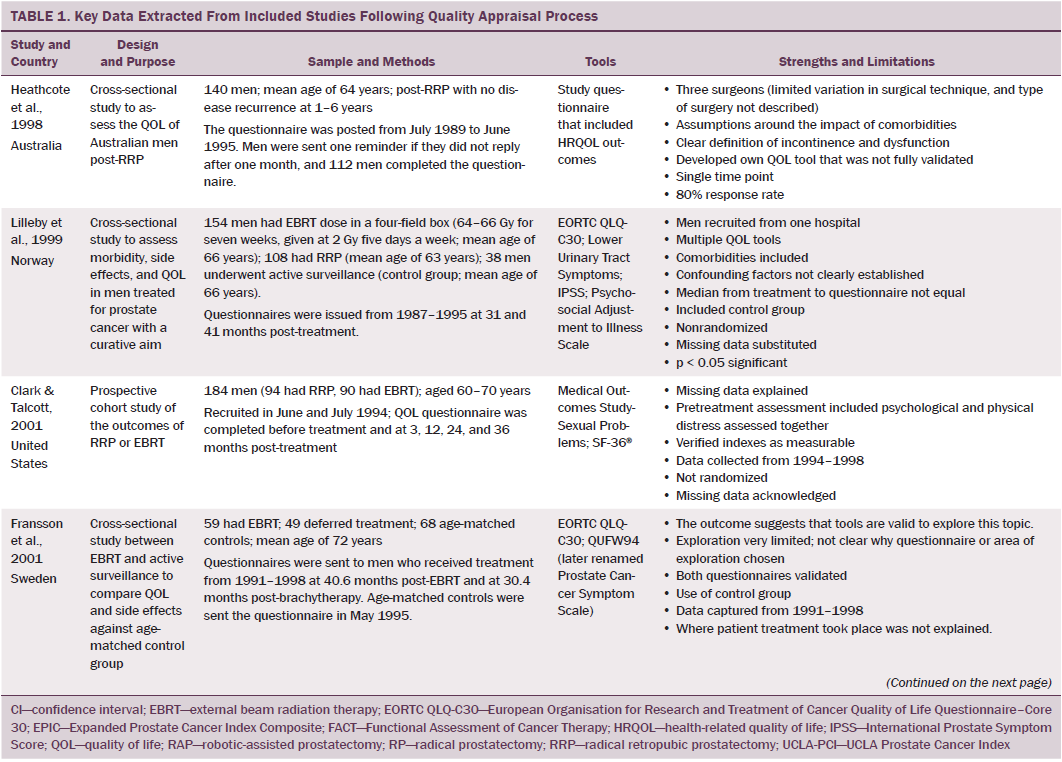

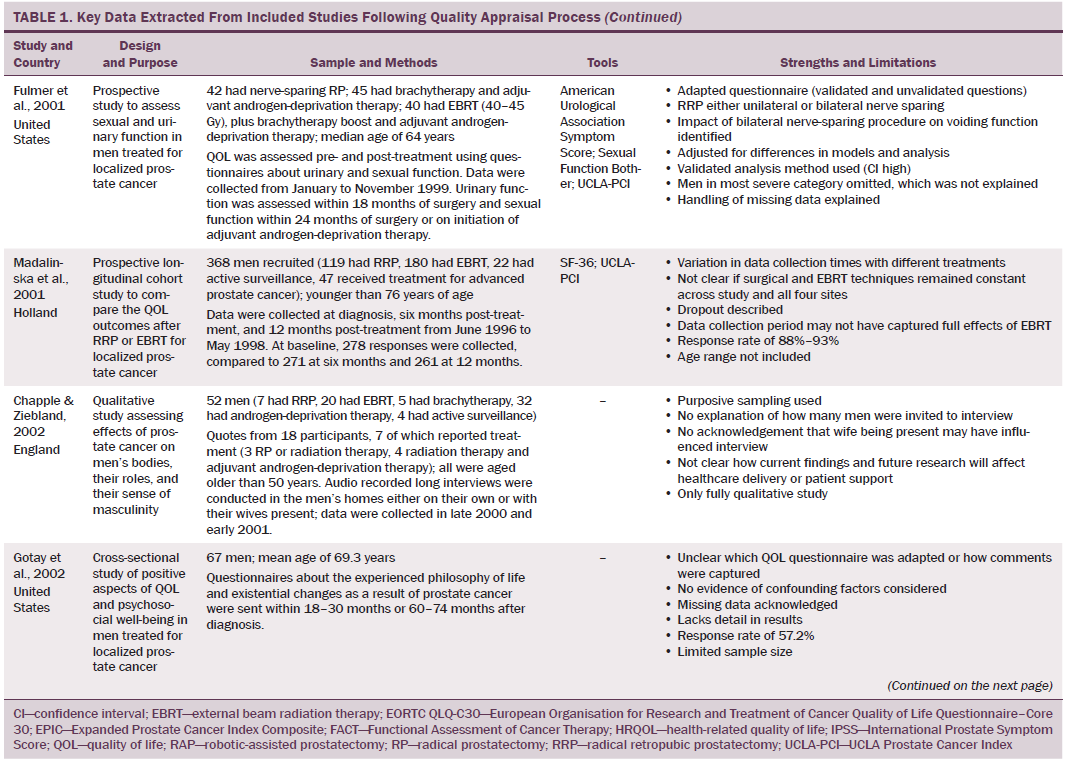

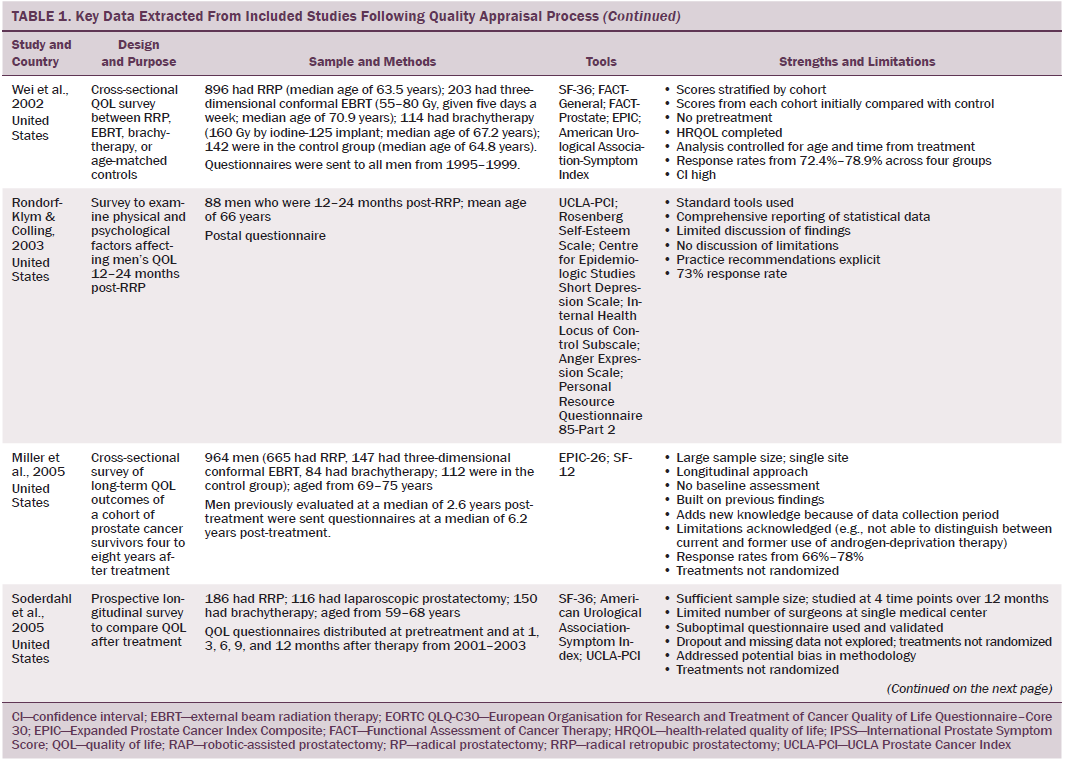

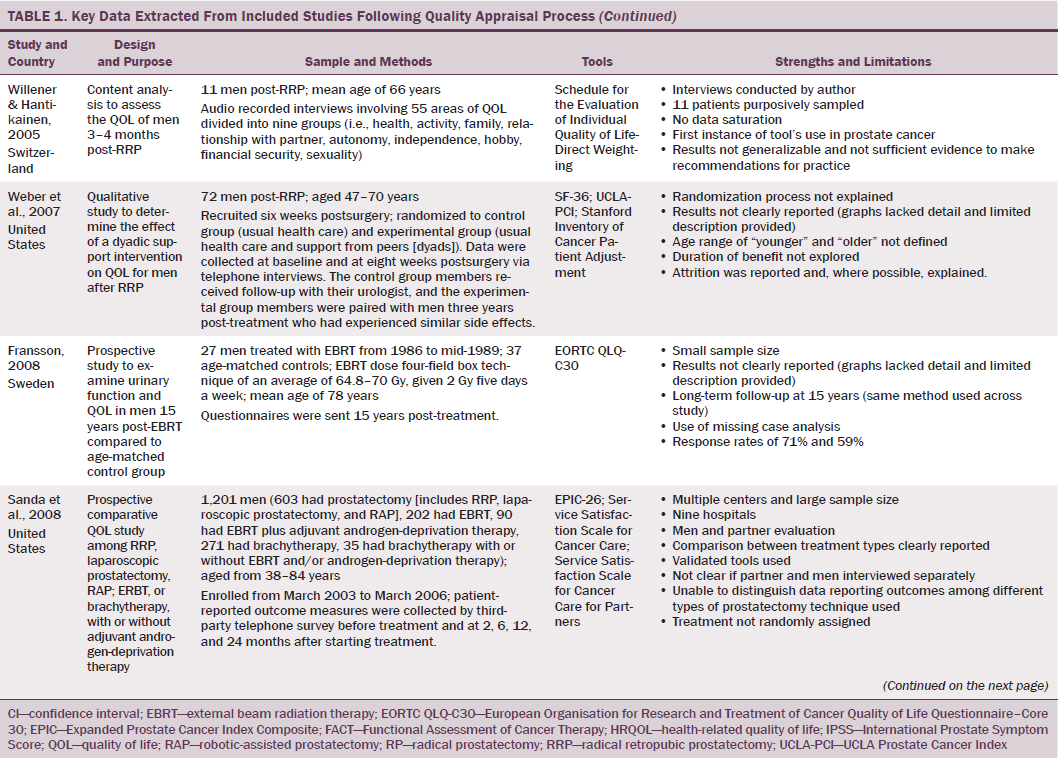

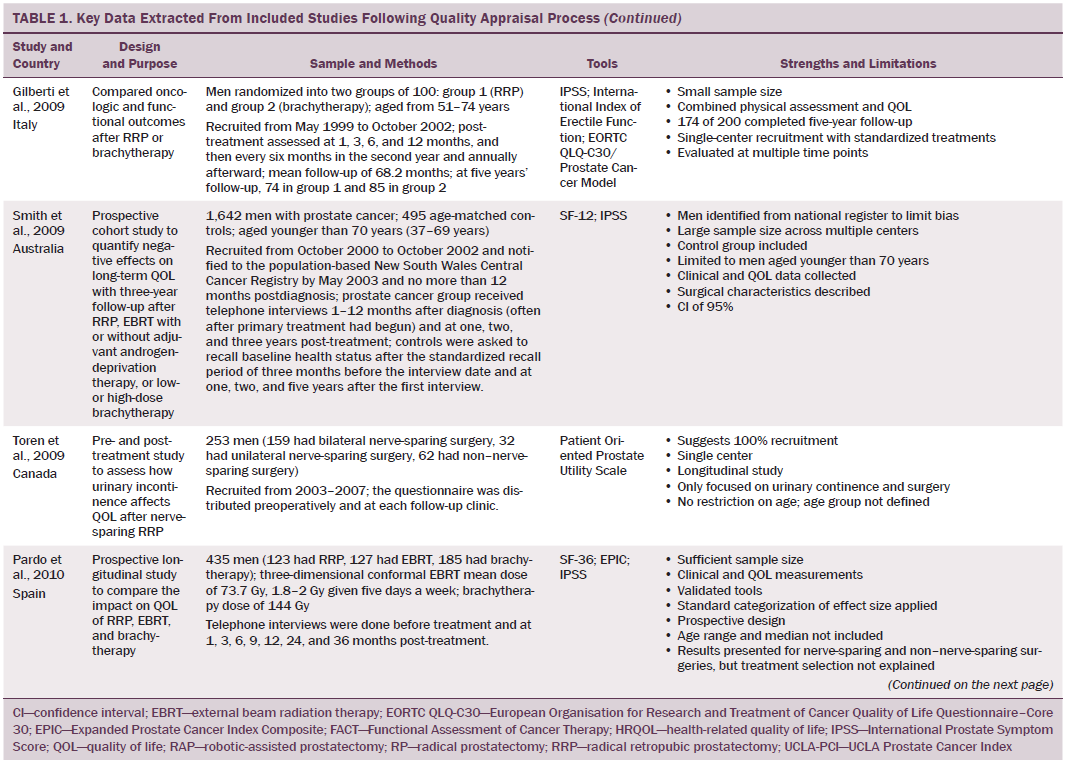

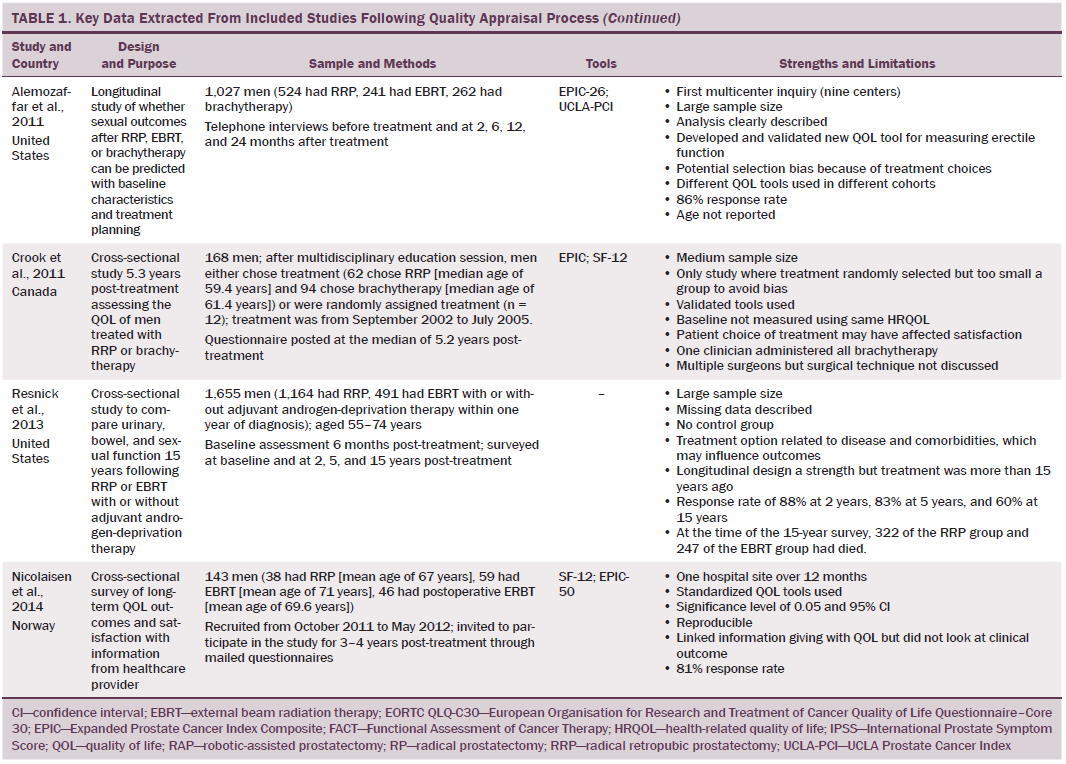

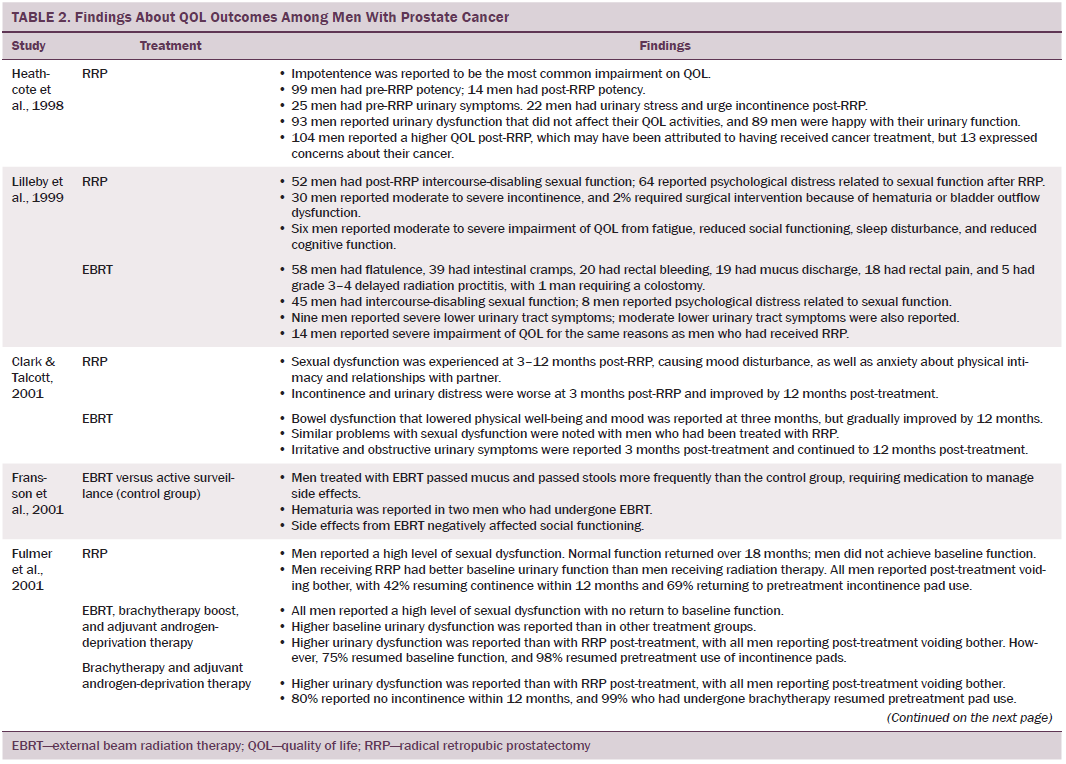

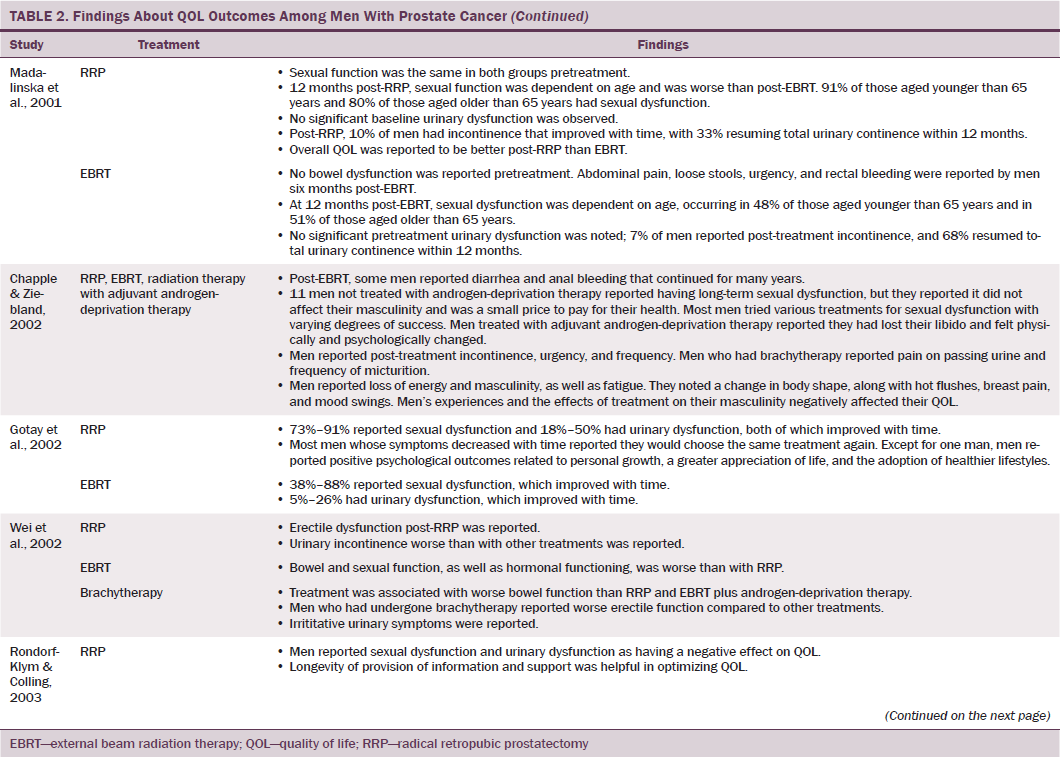

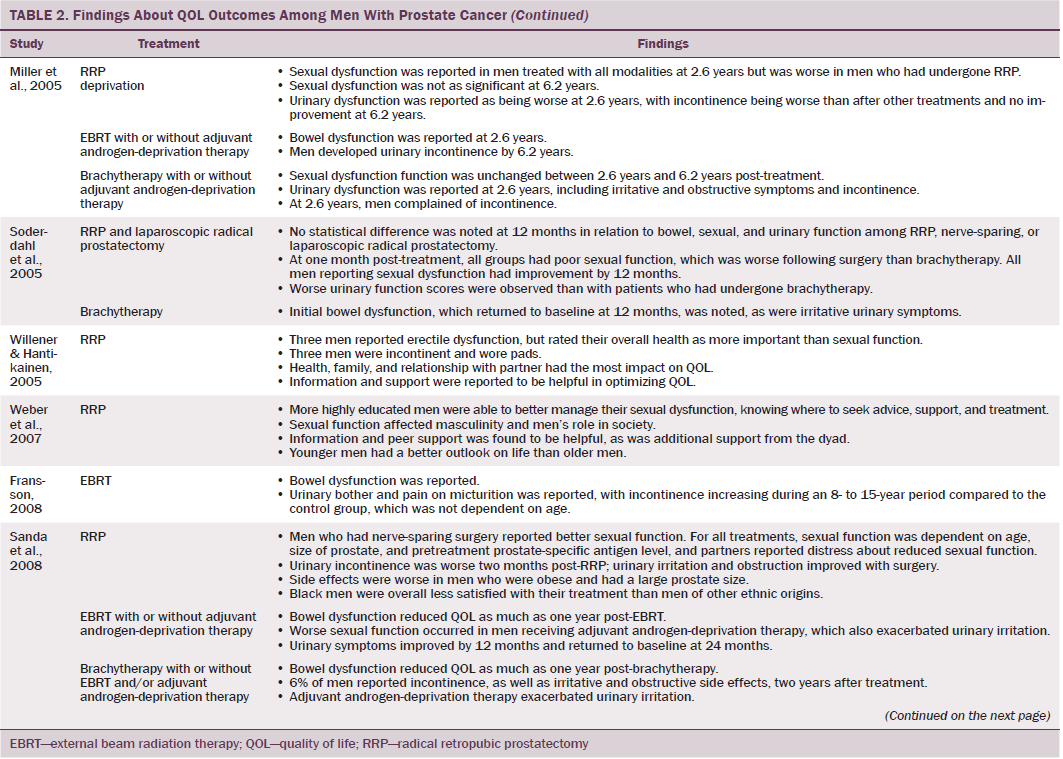

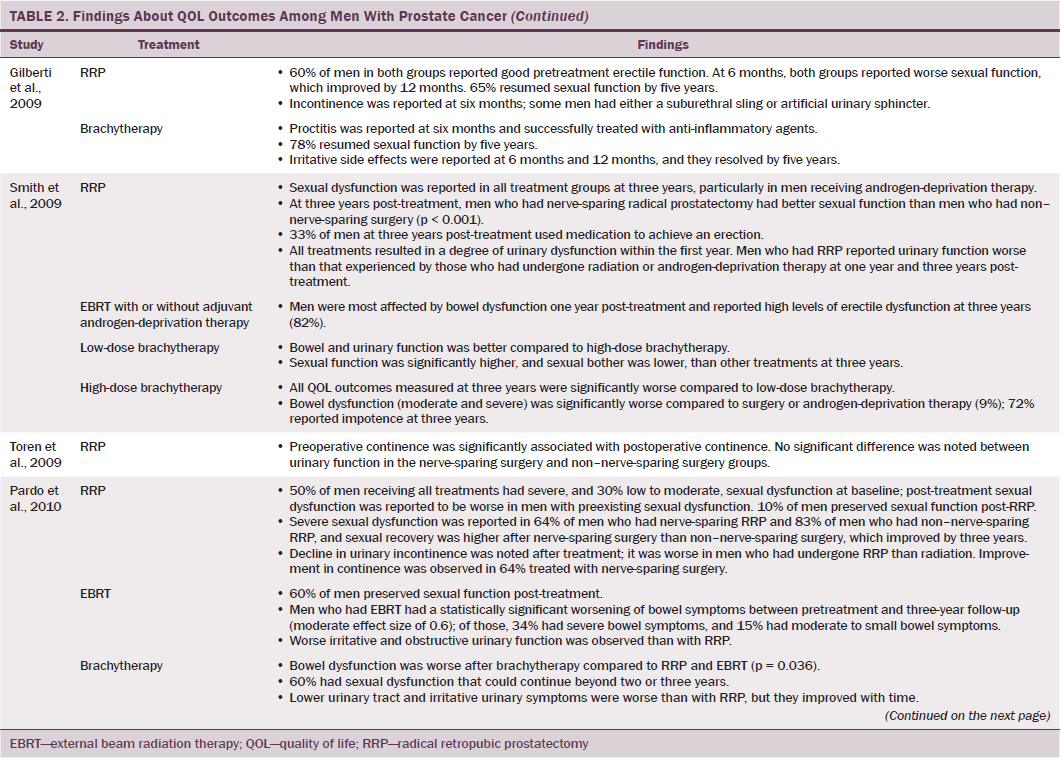

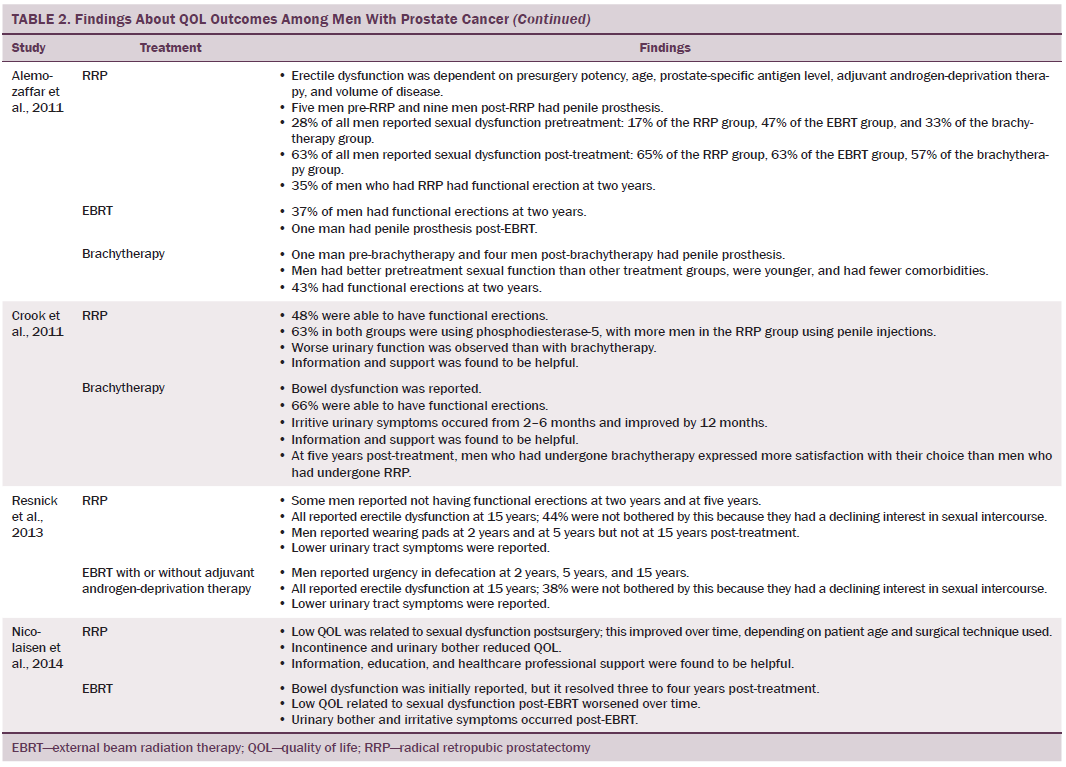

Data were independently extracted by two researchers using data extraction criteria (see Table 1). Articles were ordered chronologically by publication date. Functional QOL outcomes were commonly reported as side effects of treatment and presented in terms of loss of function or impaired function of body systems, often described as “dysfunction.” Therefore, using a data-driven approach (Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005), terminology of dysfunction was used to sort reported functional QOL outcomes following different types of treatment for localized prostate cancer. The QOL outcomes were bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, urinary dysfunction, effects of adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy, and other findings, including fatigue (see Table 2). Findings from articles reporting qualitative and quantitative data were integrated in relation to functional QOL outcomes following each localized prostate cancer treatment.

Results

Of 2,191 articles retrieved, 70 potentially relevant articles were identified, 15 were not considered to be relevant, and 55 were retrieved in full text. Twenty-four articles reported data on the effects of prostate cancer treatment on QOL that could be extracted for review. The majority of articles reported studies conducted in the United States (n = 11), with two each in Canada, Australia, Sweden, and Norway and one each in Switzerland, Spain, Holland, England, and Italy. The majority of articles reported cross-sectional studies; however, some qualitative studies were identified. The most common data collection tools used were the EORTC QLQ-C30, IPSS, SF-36, UCLA Prostate Cancer Index, and Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite.

Quality Assessment

Using relevant CASP tools, seven articles had a CASP score of 10 or greater (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002; Crook et al., 2011; Fransson, 2008; Madalinska et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2005; Pardo et al., 2010; Resnick et al., 2013). The remaining articles had CASP scores of 8 or 9.

Effects of Radical Prostatectomy on Quality of Life

Radical prostatectomy was associated with significant sexual dysfunction. In one study that recruited 302 men who had prostatectomy, no significant difference was noted in post-treatment sexual dysfunction between men who had nerve-sparing surgery compared to non–nerve-sparing surgery (Soderdahl et al., 2005). However, other large-scale, high-quality studies reported that men who had nerve-sparing surgery had better sexual function than those who did not have nerve-sparing surgery (Pardo et al., 2010; Sanda et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2009). Many studies did not control for potential confounding factors (e.g., comorbidities); however, pretreatment sexual function, PSA level, and size of prostate were reported as confounding factors of sexual function after prostatectomy (Alemozaffar et al., 2011; Sanda et al., 2008).

Side effects reported in these studies include relative loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, inability to sustain a functional erection sufficient for penetrative intercourse, and associated psychological distress at loss of the ability to have intercourse. Heathcote et al. (1998) reported that only 14 of 99 men who had erections presurgery were able to have erections after treatment. Some studies reported that men were able to restore sexual function following medical intervention; however, Fulmer, Bissonette, Petroni, and Theodorescu (2001) reported that no men returned to their normal presurgery erectile functioning, despite treatments for erectile dysfunction or nerve-sparing surgery. Larger-scale studies that used validated data collection tools found that some normal sexual function resumed over time (Alemozaffar et al., 2011; Pardo et al., 2010), but the degree to which sexual function was restored in men recruited to participate in these studies was not specified.

Some men reported that sexual dysfunction affected their feelings about sexual intimacy and relationships (Clark & Talcott, 2001). Men complained of a change in sensation and loss of penile length, which affected their manhood and self-esteem and caused loss of identity, resulting in anger (Rondorf-Klym & Colling, 2003). However, qualitative studies reported by Chapple and Ziebland (2002) and Weber et al. (2007) did not find men’s masculinity to be affected by their sexual function. Such findings may be attributed to a positive perception men had about their treatment as a whole, prioritizing the importance of overall health and survival over sexual function (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002; Willener & Hantikainen, 2005).

Radical prostatectomy was also reported to cause urinary dysfunction. Some men had pretreatment urinary dysfunction, which was worsened by surgery (Heathcote et al., 1998; Toren et al., 2009). Toren et al. (2009) found no significant difference in urinary incontinence among 253 men who had nerve-sparing surgery, non–nerve-sparing surgery, or laparoscopic prostatectomy. Immediate post-treatment side effects were urgency and frequency of micturition; longer-term side effects were mainly moderate to severe incontinence. Several studies that reported incontinence following RRP also reported a resumption of pretreatment continence within 12 months (Clark & Talcott, 2001; Madalinska et al., 2001). Gilberti, Chiono, Gallo, Schenone, and Gastaldi (2009) reported that men with severe incontinence six months following radical prostatectomy were treated with an additional surgical intervention for incontinence. Urinary leakage and incontinence one year after treatment was more common in men treated with radical prostatectomy than with EBRT (Madalinska et al. 2001; Pardo et al., 2010) or with brachytherapy (Crook et al., 2011). Some men needed surgery for hematuria or bladder outflow obstruction after radical prostatectomy (Lilleby, Fosså, Waehre, & Olsen, 1999). Lilleby et al. (1999) also reported that, after radical prostatectomy, men had impaired QOL because of fatigue.

Effects of External Beam Radiation Therapy on Quality of Life

Wei et al. (2002) reported that the total dose of EBRT given ranged from 55–80 Gy. In other studies that reported total EBRT doses, the mean dose given to men was lower than the now recommended minimum total dose of 74 Gy (NICE, 2014). All studies that assessed bowel function in men treated with EBRT reported that EBRT caused short-term bowel dysfunction. Side effects of short-term bowel dysfunction reported in qualitative and large-scale cross-sectional studies included diarrhea, frequency and urgency of passing stool, flatulence, intestinal cramps and pain, rectal pain and bleeding, mucus discharge, and radiation proctitis (Fransson et al., 2001; Lilleby et al., 1999; Madalinska et al., 2001). Several studies found that men had bowel dysfunction for many years after treatment (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002; Miller et al., 2005; Nicolaisen, Müller, Patel, & Hanssen, 2014; Resnick et al., 2013), highlighting the importance of longitudinal studies that assess patient outcomes for years after radiation treatment. A rare incidence of a patient requiring colostomy for treatment of radiation proctitis was reported by Lilleby et al. (1999).

Gotay, Holup, and Muraoka (2002) reported equivalent incidence of sexual dysfunction between men treated with EBRT or radical prostatectomy; however, this study was small and had some methodologic limitations. Larger-scale studies that used validated data collection tools reported a lower incidence of sexual dysfunction in men treated with EBRT compared to radical prostatectomy (Clark & Talcott, 2001; Madalinska et al., 2001; Pardo et al., 2010). Still, what remains evident is that sexual dysfunction is experienced by men treated with EBRT for localized prostate cancer; this side effect is worsened by the use of adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy, older age, larger prostate, and higher pretreatment PSA level (Sanda et al., 2008). In addition, with the exception of Gotay et al. (2002), sexual function was not reported to improve with time.

Several studies reported irritative and obstructive lower urinary tract side effects that develop immediately post-EBRT (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002; Clark & Talcott, 2001; Fulmer et al., 2001; Lilleby et al., 1999; Nicolaisen et al., 2014; Resnick et al., 2013), which mostly resolved with time. However, Fransson (2008) conducted a 15-year follow-up study and found that men had long-term urinary side effects of EBRT, which were stress and urge incontinence, as well as pain on micturition. In addition, fatigue and a decline in energy levels occurred 3–12 months post-treatment and can be attributed to adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy and side effects of EBRT (Lilleby et al., 1999).

Effects of Brachytherapy on Quality of Life

Men treated with brachytherapy experienced bowel dysfunction, which was reported to be worse than after EBRT (Pardo et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2002). Because of methodologic limitations in studies that compared sexual dysfunction in men treated with RRP, EBRT, or brachytherapy (Alemozaffar et al., 2011; Crook et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2002), determining which treatment would result in better sexual function is difficult; however, RRP and brachytherapy result in sexual dysfunction that may continue for many years. All studies that evaluated urinary dysfunction following brachytherapy reported irritative symptoms (Crook et al., 2011; Fulmer et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2005; Pardo et al., 2010; Sanda et al., 2008; Soderdahl et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2002). Lower urinary tract symptoms, obstructive outflow, and incontinence were also reported (Miller et al., 2005; Sanda et al., 2008).

Effects on Quality of Life of Androgen-Deprivation Therapy Adjuvant to Radiation Therapy

A variety of endocrine function-related side effects were noted in men treated with EBRT or brachytherapy in combination with androgen-deprivation therapy, which resulted in a higher side effect profile. These included loss of energy, reduced masculinity, altered body morphology, hot flushes, breast pain, and emotional disturbances.

Discussion

Most studies reviewed reported functional QOL outcomes following treatment for localized prostate cancer. These outcomes were commonly evaluated in terms of the range, frequency, severity, and duration of physical side effects.

This review found that many men treated with radical prostatectomy experienced impaired sexual dysfunction immediately after surgery; their sexual function returned over time, but this could take several years. Sexual dysfunction was also reported in men treated with EBRT and brachytherapy but, overall, was a more significant side effect in men treated with radical prostatectomy. When baseline sexual function and other variables (e.g., age, PSA level, tumor volume, adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy) were reported, the dependency of post-treatment sexual function on these variables was evident. Some men needed penile implants to be able to resume sexual activity. Sexual dysfunction was also reported to affect some men’s perception of their masculinity.

Radiation therapy caused irritative urinary symptoms, pain on voiding, and a decline in voiding function, which affected men’s QOL. Irritative symptoms and pain on voiding improved within months of treatment. Radical prostatectomy is associated with worse urinary dysfunction than EBRT or brachytherapy; however, urinary function often improves within two years of treatment. Conversely, men treated with EBRT or brachytherapy developed urinary incontinence over time.

Most men treated with radiation therapy experienced short-term bowel dysfunction, which was mostly diarrhea, urgency, or abdominal or rectal pain. Several studies reported that bowel dysfunction resolved within one to four years following radiation treatment; long-term bowel dysfunction was also reported (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002; Resnick et al., 2013).

This review found that adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy was associated with decreased energy levels, depressed mood, and weight gain. Fatigue was particularly severe when radiation therapy was combined with adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy, and fatigue following radiation therapy could last many years. Treatment for localized prostate cancer not only affects physical aspects of QOL but also a man’s perception of his masculinity, which may be threatened by physical outcomes of the treatment and heightened by use of adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002).

Few studies have reported data on psychosocial aspects of QOL. Three studies reported data on the impact of localized prostate cancer treatment on relationships (Chapple & Ziebland, 2002; Gotay et al., 2002; Weber et al., 2007), and Clark and Talcott (2001) noted an association between the severity of symptoms and distress. No studies reported the everyday experience of men treated for localized prostate cancer following a specific type of treatment, which limits understanding of post-treatment QOL outcomes in this patient population.

Optimally, cancer treatment should provide long-term survival and meet the physical and psychosocial needs of patients and their families. Consequently, careful consideration is needed regarding treatment to promote survival, well-being, and QOL. Patient choice is a central tenet of modern healthcare systems, particularly in cancer services where treatment options have equivocal overall survival outcomes. Men who are presented with different treatment options for localized prostate cancer also need to be provided with full information about the potential harms and benefits, which can be identified from patient-reported outcome measures. This review found that QOL was often measured using health-related QOL outcome surveys that focus on one or a few body functions; when used in isolation, these surveys probably do not fully capture or reflect men’s QOL following treatment for localized prostate cancer.

The treatment decision is often influenced by numerous factors, including the provision of information, as well as peer and family support (Rondorf-Klym & Colling, 2003; Weber et al., 2007). Nicolaisen et al. (2014) suggested that men who received information pre- and post-treatment adjusted to their side effects better than those who did not. Health professionals must be fully knowledgeable about the effects of treatment on QOL, so they can appropriately inform and support men facing decisions about treatment options. In addition, health professionals need to have the skills and opportunity to build therapeutic relationships with such men to enable identification of their care priorities and provide appropriate information and support.

Limitations

This literature review is restricted to data collected from men who were treated for localized prostate cancer, not locally spread or metastatic disease. Data reviewed were also restricted to articles published in English. The findings of the review should be considered in this context.

In some studies, men were treated for localized prostate cancer more than 20 years ago, which may affect the generalizability of these findings. This review considered the surgical techniques used and radiation doses administered to ensure that those treatments and doses are still used. It also considered that because of the longevity of side effects and the relatively high survival rate from treatment for localized prostate cancer, a significant population of men who are living with outcomes from those treatments would exist. The use of robotic laparoscopic surgery has been introduced to improve outcomes in men with localized prostate cancer. Evidence indicates better outcomes in terms of perioperative morbidity and risk of positive surgical margins, but no data exists to infer any difference in urinary continence or sexual function compared to other surgical techniques (Ramsay et al., 2012). This review also focused on treatment for localized prostate cancer, which meant that some published evidence was excluded if the current authors had doubt about treatment intent.

Data were mostly collected using validated health-related QOL questionnaires that generate data about impaired function, loss of function, and resumed function of body systems. Two studies adapted validated questionnaires, and one study used a newly developed questionnaire that was not fully validated. Many studies collected data about either urinary function or sexual function, and they did not capture data related to other aspects of QOL, such as social functioning or emotional well-being. Given that QOL outcomes are subjective and specific to individuals, QOL research designs should encompass the whole experience of these men. Where data were collected via interview, whether the man’s partner was present during the interview, and if this had any influence on responses, was not always apparent.

Some of the side effects reported by the men could be attributed to or exacerbated by comorbidities associated with aging. A few studies reported baseline data, but the majority of studies did not, so the extent of loss of function because of the treatment could not always be determined. Some studies did not publish details of participants’ age, and only a few studies used age-matched controls. Some studies had age-eligibility criteria, such as excluding men above a certain age, which may have reduced the representativeness of the sample. Because of variation in the participant age range and the time of data collection following treatment across the studies, conducting a meta-analysis was not possible.

Potential for bias existed in some studies because of sample selection; some samples were self-selected, and some were purposefully selected. Significant variation also occurred across the studies in regard to the time points at which data was collected (1 month to 15 years post-treatment). Some studies were prospective and reported longitudinal data, so drawing conclusions about changes in function over time was possible. To interpret data in instances with nonresponders, proportional data was evaluated. An additional limitation to interpreting the data was lack of specificity in how QOL outcomes were defined, assessed, and measured by authors. For example, to evaluate urinary incontinence, most studies measured the number of pads used per day, which may not be a consistent measure or necessarily correlate with the severity of this side effect.

Given that the majority of the data reported functional impairment, developing a coding structure and an a priori analytical framework and conducting a content analysis would have been possible (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005). However, in an effort to conduct a comprehensive review, all types of data were included. In addition, adopting a more integrative analytical approach enabled the authors to address the purpose of the review.

Implications for Practice

The role of the nurse in supporting people with cancer, independent of the care setting, is to ensure an optimal outcome. For men treated for localized prostate cancer, this means providing information and support immediately post-treatment, for several months post-treatment, and, for some men, for three to five years. In the United Kingdom, no formal long-term assessment of men treated for prostate cancer exists; however, the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative ([NCSI], 2013) has proposed personalized care planning based on the needs of individuals. Recognition of short- and long-term effects of localized prostate cancer treatment on men’s QOL has implications across care settings, and provision of care should be planned accordingly.

Nurses require knowledge and skills (developed from practice education and experience working in teams with shared philosophies of care) to build care relationships with men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer to enable self-efficacy. The aim of patient-centered care is to assist shared decision-making about treatment options, support self-management (where appropriate), and provide emotional support (Ahmad, Ellins, Krelle, & Lawrie, 2014). This requires nurses to facilitate collaboration with men treated for localized prostate cancer who wish to manage their care; learn about their disease, treatment, side effects, and side effect management; and plan and coordinate holistic care.

Localized prostate cancer treatments, particularly radical prostatectomy, are associated with immediate and long-term sexual dysfunction and urinary dysfunction. Men who experience post-treatment sexual dysfunction may need review by a nurse specialist or a doctor working in the field of genitourinary oncology or andrology who use tools such as the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) (Rosen, Cappelleri, Smith, Lipsky, & Peña, 1999) to conduct more in-depth assessment. For example, a man who has a very low SHIM score may need referral to specialist professionals, such as a sex therapist, relationship counselor, or clinical psychologist. Men may also require a mental health assessment. A number of strategies exist for assessing urinary incontinence, including history taking and the use of validated scales (e.g., IPSS), patient diaries, and clinical investigations. Some health organizations also employ continence specialist nurses. Urinary incontinence may require medication (e.g., solifenacin succinate [VESIcare®]), the use of incontinence pads or urinary sheaths, or surgical intervention (e.g., insertion of a bladder sling).

Radiation therapy treatments primarily cause diarrhea, urgency, and pain. Nurses can educate men to use bowel diaries, guide them about obtaining continence pads, and advise about alert cards (Bladder and Bowel Foundation, 2014). In addition, nurses can advise men who experience frequent episodes of diarrhea about having a low-fiber diet, staying well-hydrated, and using anti-diarrhea agents (e.g., loperamide [Immodium®]). Codeine phosphate may also be prescribed for moderate rectal or anal pain. Men may also need referral to a gastroenterologist or, in severe cases, a colorectal surgeon.

Fatigue may be a long-term side effect of radiation therapy. In the United Kingdom, the NCSI (2013) has established Health and Wellbeing Clinics to optimize QOL outcomes related to lifestyle for people treated for cancer. Together with Macmillan Cancer Support (2012), the NCSI developed a holistic needs assessment, which is recommended for use prior to the completion of cancer treatment. The use of such assessment tools and initiatives should enable nurses to support men managing treatment-related fatigue.

A key implication of the findings of this review is that men need to have accurate information about the QOL outcomes following treatment for localized prostate cancer before treatment, so they can share in decision making, and after treatment, so they can self-manage symptoms and side effects with support from healthcare professionals and more ably adjust to the changes in their body functions. A range of studies (e.g., specialist health professionals, cancer charities, information websites for patients with cancer, peer support or patient support groups) are available to provide information to men with localized prostate cancer.

Conclusion

Research that evaluates the effect of treatments on QOL should use age-matched controls; record baseline data; ideally be prospective, longitudinal studies; and incorporate holistic, validated data collection tools. In addition, definitions and methods to measure side effects (e.g., urinary and fecal incontinence) should be defined and reported.

Few qualitative studies provide in-depth insight into the experience of men treated for localized prostate cancer. Future research that captures the everyday experience of men who have had a specific type of treatment for localized prostate cancer will aid the development of assessment tools and care interventions that focus on improving QOL outcomes. Additional research is also required to evaluate QOL outcomes following newer treatments, such as robotic laparoscopic surgery, to determine if such techniques improve outcomes related to QOL.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Eila Watson, PhD, BSc(Hons), for her comments on this manuscript.

References

Ahmad, N., Ellins, J., Krelle, H., & Lawrie, M. (2014). Person-centred care: From ideas to action. Bringing together the evidence on shared decision making and self-management support. London, UK: Health Foundation.

Alemozaffar, M., Regan, M.M., Cooperberg, M.R., Wei, J.T., Michalski, J.M., Sandler, H.M., . . . Sanda, M.G. (2011). Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA, 306, 1205–1214. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1333

Barry, M.J., Fowler, F.J., Jr., O’Leary, M.P., Bruskewitz, R.C., Holtgrewe, H.L., Mebust, W.K., & Cockett, A.T. (1992). The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. Journal of Urology, 148, 1549–1557.

Bladder and Bowel Foundation. (2014). Bowel diary. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1OeaWiZ

Chapple, A., & Ziebland, S. (2002). Prostate cancer: Embodied experience and perceptions of masculinity. Sociology of Health and Illness, 24, 820–841. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.00320

Clark, J.A., & Talcott, J.A. (2001). Symptom indexes to assess outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Medical Care, 39, 1118–1130. doi:10.1097/00005650-200110000-00009

Crook, J.M., Gomez-Iturriaga, A., Wallace, K., Ma, C., Fung, S., Alibhai, S., . . . Fleshner, N. (2011). Comparison of health-related quality of life 5 years after SPIRIT: Surgical Prostatectomy Versus Interstitial Radiation Intervention Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 362–368. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7305

Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., & Sutton, A. (2005). Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 10, 45–53. doi:10.1258/1355819052801804

European Association of Urology. (2015). Guidelines on prostate cancer. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/216D2FX

Fransson, P. (2008). Patient-reported lower urinary tract symptoms, urinary incontinence, and quality of life after external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer—15 years’ follow-up. A comparison with age-matched controls. Acta Oncologica, 47, 852–861. doi:10.1080/02841860701654325

Fransson, P., Damber, J.E., Tomic, R., Modig, H., Nyberg, G., & Widmark, A. (2001). Quality of life and symptoms in a randomized trial of radiotherapy versus deferred treatment of localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 92, 3111–3119. doi:10.1002/1097-0142

Fulmer, B.R., Bissonette, E.A., Petroni, G.R., & Theodorescu, D. (2001). Prospective assessment of voiding and sexual function after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 91, 2046–2055.

Gandaglia, G., Sammon, J.D., Chang, S.L., Choueiri, T.K., Hu, J.C., Karakiewicz, P.I., . . . Trinh, Q.D. (2014). Comparative effectiveness of robot-assisted and open radical prostatectomy in the postdissemination era. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 14, 1419–1426. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5096

Gilberti, C., Chiono, L., Gallo, F., Schenone, M., & Gastaldi, E. (2009). Radical retropubic prostatectomy versus brachytherapy for low-risk prostatic cancer: A prospective study. World Journal of Urology, 27, 607–612. doi:10.1007/s00345-009-0418-9

Gotay, C., Holup, J., & Muraoka, M. (2002). The challenges of prostate cancer: A major men’s health issue. International Journal of Men’s Health, 1, 59–72.

Heathcote, P.S., Mactaggart, P.N., Boston, R.J., James, A.N., Thompson, L.C., & Nicol, D.L. (1998). Health-related quality of life in Australian men remaining disease-free after radical prostatectomy. Medical Journal of Australia, 168, 483–486.

Kendirci, M., Bejma, J., & Hellstrom, W.J. (2006). Update on erectile dysfunction in prostate cancer patients. Current Opinion in Urology, 16, 186–195. doi:10.1097/01.mou.0000193407.05285.d8

Lilleby, W., Fosså, S.D., Waehre, H.R., & Olsen, D.R. (1999). Long-term morbidity and quality of life in patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing definitive radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 43, 735–743. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00475-1

Macmillan Cancer Support. (2012). Holistic needs assessment. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1Svf31G

Madalinska, J.B., Essink-Bot, M.L., de Koning, H.J., Kirkels, W.J., van der Maas, P.J., & Schröder, F.H. (2001). Health-related quality-of-life effects of radical prostatectomy and primary radiotherapy for screen-detected or clinically diagnosed localized prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19, 1619–1628.

McKenzie, L., & van der Pol, M. (2009). Mapping the EORTC QLQ C-30 onto the EQ-5D instrument: The potential to estimate QALYs without generic preference data. Value in Health, 12, 167–171.

Miller, D.C., Sanda, M.G., Dunn, R.L., Montie, J.E., Pimentel, H., Sandler, H.M., . . . Wei, J.T. (2005). Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: Health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy external radiation, and brachytherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 2772–2780. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.07116

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1006–1012. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

National Cancer Survivorship Initiative. (2013). Living with and beyond cancer: Taking action to improve outcomes. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1QjxxPI

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014). Prostate cancer: Diagnosis and management. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1U5JFXf

Nicolaisen, M., Müller, S., Patel, H.R., & Hanssen, T.A. (2014). Quality of life and satisfaction with information after radical prostatectomy, radical external beam radiotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy: A long-term follow-up study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 3403–3414. doi:10.1111/jocn.12586

Nilsson, S., Norlén, B.J., & Widmark, A. (2004). A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in prostate cancer. Acta Oncologica, 43, 316–381. doi:10.1080/02841860410030661

Pagliarulo, V., Bracarda, S., Eisenberger, M.A., Mottet, N., Schröder, F.H., Sternberg, C.N., & Studer, U.E. (2012). Contemporary role of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. European Urology, 61, 11–25. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2011.08.026

Pardo, Y., Guedea, F., Aguiló, F., Fernández, P., Macías, V., Mariño, A., . . . Ferrer, M. (2010). Quality-of-life impact of primary treatments for localized prostate cancer in patients without hormonal treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4687–4696. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3245

Ramsay, C., Pickard, R., Robertson, C., Close, A., Vale, L., Armstrong, N., . . . Soomro, N. (2012). Systematic review and economic modelling of the relative clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery and robotic surgery for removal of the prostate in men with localized prostate cancer. Health Technology Assessment, 16, 1–313. doi:10.3310/hta16410

Resnick, M.J., Koyama, T., Fan, K.H., Albertsen, P.C., Goodman, M., Hamilton, A.S., . . . Penson, D.F. (2013). Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 436–445. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209978

Rondorf-Klym, L.M., & Colling, J. (2003). Quality of life after radical prostatectomy [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, E24–E32. doi:10.1188/03.ONF.E24-E32

Rosen, R.C., Cappelleri, J.C., Smith, M.D., Lipsky, J., & Peña, B.M. (1999). Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research, 11, 319–326. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472

Sanda, M.G., Dunn, R.L., Michalski, J., Sandler, H.M., Northouse, L., Hembroff, L., . . . Wei, J.T. (2008). Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 1250–1261. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa074311

Shelley, M.D., Kumar, S., Coles, B., Wilt, T., Staffurth, J., & Mason, M.D. (2009). Adjuvant hormone therapy for localised and locally advanced prostate carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 35, 540–546. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.05.001

Smith, D.P., King, M.T., Egger, S., Berry, M.P., Stricker, P.D., Cozzi, P., . . . Armstrong, B.K. (2009). Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: Population based cohort study. BMJ, 339, b4817. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4817

Soderdahl, D.W., Davis, J.W., Schellhammer, P.F., Given, R.W., Lynch, D.F., Shaves, M., . . . Fabrizio, M.D. (2005). Prospective longitudinal comparative study of health-related quality of life in patients undergoing invasive treatments for localized prostate cancer. Journal of Endourology, 19, 318–326. doi:10.1089/end.2005.19.318

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2003). Quality in qualitative evidence: A framework for assessing research evidence. A quality framework. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1oGESzm

Toren, P., Alibhai, S.M., Matthew, A., Nesbitt, M., Kalnin, R., Fleshner, N., & Trachtenberg, J. (2009). The effect of nerve-sparing surgery on patient-reported continence post-radical prostatectomy. Canadian Urological Association Journal, 3, 465–470.

Valerio, M., Ahmed, H.U., Emberton, M., Lawrentschuk, N., Lazzeri, M., Montironi, R., . . . Polascik, T.J. (2014). The role of focal therapy in the management of localised prostate cancer: A systematic review. European Urology, 66, 732–751. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.05.048

Ware, J.E., Jr., & Gande, B. (1994). The SF-36 Health Survey: Development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA Project. International Journal of Mental Health, 23, 49–73. doi:10.1080/00207411.1994.11449283

Weber, B.A., Roberts, B.L., Yarandi, H., Mills, T.L., Chumbler, N.R., & Algood, C. (2007). Dyadic support and quality-of-life after radical prostatectomy. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender, 4, 156–164. doi:10.1016/j.jmhg.2007.03.004

Wei, J.T., Dunn, R.L., Sandler, H.M., McLaughlin, P.W., Montie, J.E., Litwin, M.S., . . . Sanda, M.G. (2002). Comprehensive comparison of health-related quality of life after contemporary therapies for localized prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 557–566. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.2.557

WHOQOL Group. (1998). The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science and Medicine, 46, 1569–1585. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00009-4

Willener, R., & Hantikainen, V. (2005). Individual quality of life following radical prostatectomy in men with prostate cancer. Urologic Nursing, 25, 88–90, 95–100.

About the Author(s)

Baker is a lead clinical nurse specialist at the University College Hospital in London; Wellman is a Cancer Research UK consultant nurse at Churchill Hospital in Oxford; and Lavender is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences at Oxford Brookes University in Oxford, all in England. This study was funded by Higher Education Thames Valley (previously South Central Strategic Health Authority). Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Forum or the Oncology Nursing Society. Baker and Lavender contributed to the conceptualization and design. Baker completed the data collection. Lavender provided the statistical support. All authors contributed to the analysis and manuscript preparation. Baker can be reached at hilary.baker@uclh.nhs.uk, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted February 2015. Accepted for publication August 4, 2015.