Young Adults’ Perceptions of the Venturing Out Pack Program as a Tangible Cancer Support Service

Purpose/Objectives: To explore the extent to which contents contained in a backpack called the Venturing Out Pack (Vo-Pak) assist in meeting the practical, psychosocial, and informational needs of young adults (YAs), as well as how the Vo-Pak could better meet the needs of YAs.

Research Approach: Qualitative, descriptive.

Setting: A university-affiliated adult hospital cancer center in Montreal, Quebec.

Participants: 12 YAs treated for cancer.

Methodologic Approach: One-time, individual, semistructured interviews. Verbatim transcripts underwent thematic analysis.

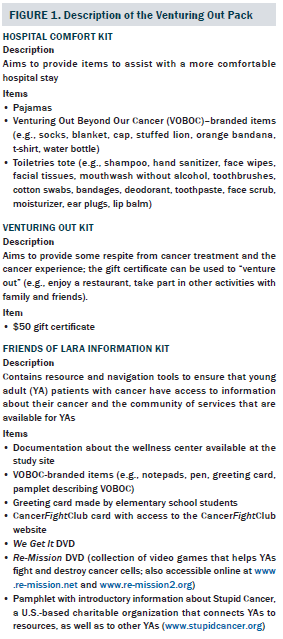

Findings: Participants viewed the Vo-Pak as a welcoming, ready-to-use, timely package that met many cancer-related needs. The Vo-Pak contains three kits: the Hospital Comfort Kit, which was seen as a hands-on resource that provided quality products; the Venturing Out Kit, which was viewed as a catalyst for connecting with others; and the Friends of Lara Information Kit, which assisted participants in locating relevant support resources. Participants recommended earlier delivery and broader dissemination of the Vo-Pak program.

Conclusions: This program adds value to efforts to enhance cancer care for YAs. Integrating participants’ recommendations contributes to the overarching goal of comprehensive person-centered care to an underserved segment of the cancer population.

Interpretation: The Vo-Pak program could be optimized by re-engaging healthcare professionals in its broader dissemination. Champions may be added to optimize the successful implementation of tangible support programs. YAs seem eager to connect with peers. The Vo-Pak can be instrumental in facilitating these connections and enabling these exchanges.

Jump to a section

The young adult (YA) patient group has been increasingly recognized as a distinct entity with specific needs within the cancer community (D’Agostino, Penney, & Zebrack, 2011; De et al., 2011; Ramphal et al., 2011). Researchers have found that some of the informational, psychosocial, and practical needs of this population remain unmet and recommend additional research to understand members’ unmet needs (Palmer, Mitchell, Thompson, & Sexton, 2007; Patterson, Millar, Desille, & McDonald, 2012; Ramphal et al., 2011; Taylor, Pearce, Gibson, Fern, & Whelan, 2012; Zebrack et al., 2013). Although initiatives to address these needs may lead to positive outcomes, such as improvement in psychosocial well-being (Zebrack et al., 2013), the supportive care of YAs remains suboptimal and, therefore, has become a national priority.

Founded in 2001 by cancer survivor Doreen Edward, Venturing Out Beyond Our Cancer (VOBOC) is a nonprofit charitable organization based in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, that is committed to providing adolescents and YAs (AYAs) with tangible support services (VOBOC, 2014). VOBOC’s Venturing Out Pack (Vo-Pak) is a free backpack containing tools and resources to help AYAs throughout their cancer trajectory (VOBOC, 2014). The Vo-Pak program has been well received since its launch in 2003, with more than 800 Vo-Paks delivered to AYAs at seven university-affiliated hospitals in Montreal; more than 140 Vo-Paks were delivered in 2012 alone. Since its implementation, VOBOC has delivered more than 1,100 Vo-Paks, including 175 delivered in 2015 to newly diagnosed YAs. Despite the Vo-Pak program’s increasing popularity, the current study is the first step toward a multiphase approach to evaluate it. The purpose of this study was to explore YAs’ perceptions of the provision of hands-on materials provided through the Vo-Pak program. Although Vo-Paks are provided to adolescents as well as YAs, the current study focused solely on the needs and perceptions of YAs because it was conducted in an adult healthcare setting. Consequently, the literature review focused on the needs of YAs as well.

Literature Review

About 200,000 Canadians were expected to be diagnosed with cancer in 2015, including 2,600 YAs aged 15–29 years; in addition, about 8,000 AYAs are diagnosed each year in Canada (Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics, 2015). YAs comprise a distinct group of patients with cancer, and they have informational, psychosocial, and practical needs that remain unmet by existing cancer services (Albritton & Bleyer, 2003; Fernandez & Barr, 2006; Ramphal et al., 2011; Zebrack et al., 2013). An informational need refers to the desire for concrete, age-appropriate, and well-defined knowledge regarding medical, emotion-regulation, and practical information (Zebrack, Chesler, & Kaplan, 2010). YAs often receive information that is too broad, improperly delivered, or given at inappropriate times (Kyngäs et al., 2001; Lockhard & Berard, 2001; Palmer et al., 2007; Wicks & Mitchell, 2010). A psychosocial need refers to the need for dignity, competence, and acceptance (Kerr, Harrison, Medves, & Tranmer, 2004), whereas a practical need refers to assistance in accomplishing goals or tasks (Dyson, Thompson, Palmer, Thomas, & Schofield, 2012; Kerr et al., 2004). Ideally, these unmet needs should be addressed in an age-appropriate manner, and important problems (e.g., future infertility) must be addressed prior to the commencement of treatment (Palmer et al., 2007). YAs are also confronted with unmet practical needs for achieving normality, independence, and healthy relationships (Zebrack & Butler, 2012), which influences their psychosocial well-being (Taylor et al., 2011). In addition, the needs of this patient population change gradually over time (Millar, Patterson, & Desille, 2010). For example, YAs report more unmet needs regarding informational and practical support within the first year of diagnosis, compared to the need for psychosocial support five years after diagnosis (Dyson et al., 2012; Millar et al., 2010). Several predictive factors exist for unmet needs, including disease stage, time since diagnosis, and physical and mental quality of life (McDowell, Occhipinti, Ferguson, Dunn, & Chambers, 2010).

Tangible Support Interventions to Address Unmet Needs

A handful of support interventions have been developed and tested to address the unmet needs of YAs, including (a) informational support interventions (Beale, Kato, Marin-Bowling, Guthrie, & Cole, 2007; Canada, Schover, & Li, 2007); (b) psychosocial support interventions (e.g., peer support and skill-based interventions) (Aubin, Rosberger, Petr, & Gerald, 2011; Barrera, Damore-Petingola, Fleming, & Mayer, 2006; Robison, 2011; Schultz & Mir, 2012; Zebrack, Bleyer, Albritton, Medearis, & Tang, 2006); and (c) practical support interventions (Bingen & Kupst, 2010; Curran, Saylor, & Portrey, 2012; Olsen & Harder, 2011). Most interventions do not meet the range of needs encountered by YAs (D’Agostino et al., 2011). The availability of tangible support services may be crucial in addressing these needs and quality care gaps (Zebrack et al., 2013). However, few researchers have conducted in-depth interviews with YAs to explore the extent to which particular types of tangible support are construed as more or less helpful (Taylor et al., 2012; Zebrack et al., 2013). Determining whether available tangible support services address the needs of YAs, as well as ways to enhance these services, is important. Objectives of the current study were to explore the extent to which contents contained in a backpack called the Vo-Pak helped to meet the practical, psychosocial, and informational needs of YAs, as well as how the Vo-Pak could better meet the needs of YAs.

Methods

Incidence of Screening

Following institutional ethical approvals from McGill University and the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, a qualitative study was conducted to explore YAs’ perceptions of the Vo-Pak. Purposeful sampling techniques were used to recruit YAs diagnosed with cancer from the Segal Cancer Centre at the Jewish General Hospital, a university-affiliated adult cancer care center in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Individuals were eligible to participate in the study if they (a) were aged 18–39 years, (b) were diagnosed with any type of cancer within the past year, (c) were receiving cancer treatment or follow-up care at the study site, and (d) had received the Vo-Pak. The study remained open to enrollment from September 2013 to December 2013. Given the number of Vo-Paks already delivered across the seven sites, a multisite survey would have been informative. However, this was not feasible within the context and resources allocated for the project. A descriptive, qualitative design was selected based on the belief that the study findings would lend insight into the design of a multisite survey.

Procedures

The study was advertised by posting study flyers in the oncology inpatient unit and outpatient clinic and by inserting a study pamphlet in the Vo-Pak. Members of the multidisciplinary team, who provided clinical care to the YAs and had legal access to patient medical files, served as clinical partners and facilitated the recruitment process using a standardized approach. Any uncertainties regarding eligibility were clarified between the clinical partners and the student researcher. Clinical partners shared the contact information of interested eligible YAs with the student researcher who presented them with a verbal and written explanation of the study and obtained informed consent.

Materials

The Vo-Pak is a specially designed backpack containing three kits: (a) the Hospital Comfort Kit; (b) the Venturing Out Kit; and (c) the Friends of Lara (FOL) Information Kit (see Figure 1). Separate versions are available for male and female patients (VOBOC, 2014). At the study site, all YAs with a new cancer diagnosis received a Vo-Pak from a member of the healthcare team during their first day of cancer treatment. The provision of the Vo-Pak is guided by the following underlying principles:

• Vo-Paks are delivered by the oncology team as a greeting to patients.

• The Vo-Pak provides tools, resources, and pathways to access supportive services but delivers these in a nonintrusive way.

• VOBOC works closely with oncology teams to support their needs in serving patients.

• VOBOC works to equip patients with tools and resources that will help to improve the navigation and experience.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected through a one-time, face-to-face, audio-recorded, semistructured interview that lasted from 45–60 minutes. The research team (i.e., student researcher, principal investigator, and co-investigator) created the interview guide with input from VOBOC (a community partner). The guide included two sections: exploring how the Vo-Pak meets the informational, psychosocial, and practical needs of YAs and describing how the Vo-Pak may be enhanced. After the interview, the researcher wrote observational field notes that were added to the interview transcripts for data analysis.

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s (1978) method as follows: (a) each interview was transcribed verbatim; (b) the transcript was read over for a general understanding; (c) the transcripts were re-read to identify specific phrases related to the perceptions of YAs’ needs and perceptions of the Vo-Pak; and (d) statements were grouped into categories, which were distilled and then analyzed for patterns and themes, and relationships between themes were considered. Salient points of collected data, as interpreted by members of the research team, were compared and discussed. As themes emerged from later interviews, earlier transcripts were reanalyzed.

Results

Description of the Sample

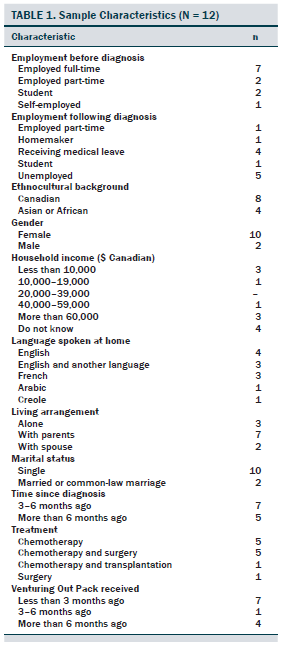

Clinical partners screened 18 YAs for eligibility and approached 16 of them. Two YAs could not be contacted. Among the 16 YAs who agreed to meet with the student researcher, four participants declined participation because they were feeling unwell. The final sample included 12 participants who provided informed consent, completed the sociodemographic questionnaire, and participated in the interviews. The participants ranged in age from 20–35 years. The sample included participants diagnosed with Hodgkin disease, brain tumor, Ewing sarcoma, acute myeloid leukemia, nasopharyngeal cancer, and breast cancer. Participants identified their ethnocultural background as Canadian, Quebecer, Algerian, Lebanese-Armenian, or Sri-Lankan. Additional sociodemographic characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Themes

Most participants received the Vo-Pak on their first day of cancer treatment from a member of the healthcare team. Four participants received the Vo-Pak within three months after their diagnosis. Four major themes emerged. The first theme, “The Vo-Pak is a welcoming ‘ready-to-go’ package,” reflects participants’ overall impressions. The subsequent themes described how each kit met some of the participants’ needs. The other themes were as follows: “The Hospital Comfort Kit: Helpful ‘hands-on’ quality products;” “The Venturing Out Kit: A catalyst for connecting and getting out;” and “The FOL Information Kit is a dispatcher to available resources.” Embedded within these themes were participants’ recommendations for optimal use.

The Venturing Out Pack is a welcoming “ready-to-go” package: Participants described the Vo-Pak as a “well designed,” “well-thought-out,” and “friendly, welcoming package.” Participants emphasized that the Vo-Pak helped them in practical ways by (a) offering essential items (e.g., personal hygiene products) that met their physical needs, (b) providing attractive clothing for a potential hospitalization (e.g., pajamas), and (c) giving them useful accessories for daily life and clinical appointments (e.g., notepads). In addition, participants indicated that the ready-to-go package helped them to feel prepared for their hospital visit and also indirectly taught them how to prepare for future hospital stays. As was intended, the Vo-Pak (particularly the Hospital Comfort and FOL Information kits) also served as an entry tool for meeting participants’ psychosocial and informational needs. Participants perceived that the contents within the Vo-Pak served as their first point of contact with available community support services and believed that such programs could help them to build their social networks (e.g., through connecting with peers with cancer) and increase their knowledge of cancer.

The Hospital Comfort Kit: Helpful “hands-on” quality products: Most participants praised the Hospital Comfort Kit for its appropriateness and usefulness. Participants found that many of the items were helpful (including the personal hygiene items, socks, caps, and bandanas) and also offered suggestions for improvements (e.g., different clothing sizes, increased quantities). As expressed by one participant, “All the cosmetics inside the pouch are really good, like, for [a] cancer patient. . . . There’s everything in it, the kind of things that you need.” It saved patients from having to rely on someone to prepare or purchase items before their next hospital visit. The few useful items went a long way toward making participants feel better. Overall, participants said they found the kit to contain helpful and hands-on quality products.

The Venturing Out Kit: A catalyst for connecting and getting out: Those who used the Venturing Out Kit or learned about the kit during the interview construed the kit as a catalyst for connecting with others and enabling them to get out. Two subthemes emerged: “Connecting with others” and “Free outings as a means to reduce guilt over spending.” The subtheme of “Making this resource more visible” emerged as a recommendation.

Connecting with others: Participants who used the Venturing Out Kit reported feeling less social isolation and loneliness by keeping themselves entertained and discussing their cancer-related experiences with others. The Venturing Out Kit permitted participants to “get out” through a voucher to a restaurant. Participants welcomed the break from their cancer treatment and the chance to spend time with others. “I think it’s amazing,” said one participant. “It makes people happy. . . . It’s like just a little smile.”

In contrast, participants who did not use the venturing out feature expressed a strong need for resources to help them to connect or reconnect with others, particularly cancer survivors or patients with cancer who were of a similar age. Those who had rare tumors thought that being able to communicate with others who had the same diagnosis was crucial. One explained, “I have a rare tumor that I can’t find anybody to talk about with, because nobody really knows where to look or who has it.” The opportunity for participants to connect with peers was limited because of the difficulty in finding age-appropriate peers and the inability to find facilitators to bring them together.

Free outings as a means to reduce guilt over spending: Following their cancer diagnoses, several participants experienced financial burdens because of changes in their employment status. In addition, they had to absorb cancer-related costs, such as paying for medication and travel. The gift certificate contained in the Venturing Out Kit served as a break from the financial strain and helped participants by providing a one-time free outing, removing the guilt of spending money on leisure activities. One participant explained the benefits of receiving such an item.

For me, personally, it’s great because it alleviates some financial expenses, and it will encourage me to think of something fun to do with our family. . . . I think how it’s a great thing to offer to people because, again, when we have cancer, we have to spend a little more on drugs, parking, and gas to get here.

Making this resource more visible: Reporting feeling overwhelmed by their diagnosis and treatment, many participants (8 out of 12) overlooked the $50 gift certificate in their Venturing Out Kit. Those who learned of the kit during their interview suggested that something should be done to make the presence of the gift certificate more obvious, such as an explanatory letter including instructions on how to redeem the gift certificate and its purpose. One participant suggested that VOBOC could “make it more obvious . . . tell us what it is for so we can benefit from it.” Other participants suggested additional opportunities to venture out, such as an application to the Make-A-Wish Foundation and the provision of event tickets to connect with peers (e.g., tickets to hockey games or concerts). They also suggested that an annual VOBOC gathering for all Vo-Pak recipients be implemented.

The Friends of Lara Information Kit is a dispatcher to available resources: Participants who reviewed the FOL items found most of them to be helpful, particularly those that introduced them to new resources. One participant explained further.

Going through these treatments is a mess because you don’t know anybody. . . . By knowing these people through the information you get, it could be easier for you because you will know people in the same situation. You could discuss that. With these services, you can find people like you and know about your cancer and find new resources. . . . You could have a sort of social life.

Some participants enjoyed learning about various activities offered at the Hope and Cope Wellness Center, a community-based organization offering free services to cancer survivors in the Montreal area. Despite the reported usefulness of this information kit, several informational needs about medical treatment remained unmet; however, the materials provided in the Vo-Pak were never intended to address this need because VOBOC ascertains that members of the healthcare team should provide this information. Participants’ unmet needs included the need for more information about treatment options, side effects, prognosis, nutrition, exercise, fertility issues, and complementary medicine. Many participants expressed that the lack of information from their healthcare professionals that was tailored to their diagnosis and unique situation contributed to the frustration they experienced. One participant elaborated on these feelings.

I like to know exactly what’s going on . . . what to expect from the treatment. . . . Sometimes I have little information, and I used to Google specific information about [the] brain tumor, but, still, it was hard to get what you want exactly.

Two subthemes emerged from participants’ explanations of the factors that prevented them from using the resources available in the FOL Information Kit: optimal timing for delivery and promoting Vo-Pak awareness.

Optimal timing for delivery of the Friends of Lara Information Kit: The time of diagnosis and the commencement of treatment were fraught with shock, distress, and many illness demands. As a result, many participants overlooked the FOL Information Kit, which included information about CancerFightClub (www.cancerfightclub.com), a social networking website for the YA cancer community, and other organizations, such as Stupid Cancer (www.stupidcancer.org), a U.S.-based charity supporting YAs with cancer, and Young Adult Cancer Canada (www.youngadultcancer.ca), a Canada-based charity supporting YAs with cancer through retreats and local cafes.

Participants viewed the timing of the introduction of the FOL Information Kit as problematic. Some suggested that a VOBOC representative could provide the information and showcase how the Vo-Pak serves as an entry tool to services and resources. This information could be delivered one or two months after the beginning of treatment in the form of a video or a verbal presentation. By that point, patients would have reached a level of acceptance where they would be open to learning about resources to help them recover. One participant described not being ready for this information at the time it was presented.

There was a lot of information . . . in the bag. And I wasn’t ready . . . to read it when I first had the bag, but, after some time, after a month or two or three, I started reading it.

Promoting Venturing Out Pack Program awareness: Participants recommended specific ways to promote the uptake of the contents contained in the Vo-Pak. They suggested raising awareness of the CancerFightClub card (similar to a business card inserted in the backpack) as a resource for YAs and healthcare professionals in all hospitals that distribute Vo-Paks. In addition, they suggested making the Re-Mission DVD optional to YAs. Others suggested replacing the We Get It DVD with a VOBOC DVD that would introduce patients to “what it is like to be a YA with cancer” and the VOBOC organization, services, and Vo-Pak contents. They wanted more survivor stories and fewer stories about those who died, as well as for VOBOC to have a greater presence in the clinical setting (e.g., increase number of VOBOC pamphlets and posters in the YA clinic).

Discussion

A qualitative, descriptive study was conducted with 12 YAs to explore the extent to which a tangible support service (i.e., the Vo-Pak) helped to meet their needs and describe ways to enhance the Vo-Pak. Overall, participants positively viewed the Vo-Pak as a program to help meet their practical and psychosocial needs. They discussed the importance of peer support and the timely delivery of the Vo-Pak, as well as offered numerous suggestions to enhance the program.

Practical and Psychosocial Needs

Collectively, participants welcomed the Vo-Pak, a tangible cancer support service as a ready-to-go package. By offering hands-on products, the Vo-Pak comforted participants during their hospitalization, helped to meet their practical needs, and provided “intangible support.” The current authors’ findings are similar to those of Nordstrom (1988) who evaluated the use of an autosyringe backpack for children receiving chemotherapy and found that the provision of a backpack with various items provided greater comfort to children during their hospitalization.

The Vo-Pak also provided YAs with a gift certificate to help pay for a one-time outing, which was greatly appreciated. The provision of a guilt-free outing serves as a critical reminder to the cancer community of the financial burden imposed on the YA population. Their financial burden is different than that of the older adult or childhood populations because they (a) require intensive and expensive treatments, (b) are often uninsured, and (c) experience financial setbacks that have a lasting economic impact on them (Nelson, 2011). Many of the participants stopped working following their diagnosis and were forced to rely on their support networks to deal with their household and cancer-related expenses. This finding is consistent with Pentheroudakis and Pavlidis (2005) who found that lost work may force YAs to rely on family help at a time when financial independence is the goal. This finding is also congruent with Levy (2002) who concluded that the financial costs of cancer may be a tremendous burden on patients and their families. The stress associated with these financial concerns may also impede successful coping and interfere with treatment recommendations.

Importance of Peer Connections

Participants who used the venturing out gift—a tangible item—perceived it as an entertaining distraction and a catalyst for connecting with others, which led to the provision of intangible support. This need to connect with peers was viewed as critical. The current authors’ findings are congruent with D’Agostino et al. (2011) and Zebrack (2011) who highlighted the importance of peer interaction and its potential to improve the psychosocial well-being of YAs. Similar to Zebrack (2009), participants in the current study emphasized a desire to participate in programs with other cancer survivors of their own age. Doing so may help YAs to feel less isolated from their peers and encourage elements of normality within the cancer experience (Smith, Davies, Wright, Chapman, & Whiteson, 2007). Peer support programs have been proven to help YAs feel more in control by imparting information about the disease and treatment, promoting psychosocial tools and strategies, and encouraging them to take on more decision-making responsibilities (Ussher, Kirsten, Butow, & Sandoval, 2006). These programs are recognized as an effective forum for psychosocial support, resulting in consistent educational, emotional, and instrumental benefits for people with cancer (Ussher et al., 2006); consequently, ensuring that YAs use the venturing out gift to connect with others is critical.

Timing

Participants were overwhelmed by their initial diagnosis and the treatments that followed; as a result, they did not use all of the items contained in the Vo-Pak. Drawing from the adolescent cancer literature, the current authors inferred that information needs to be distributed and shared at an appropriate pace by healthcare professionals who are sensitive to timing and readiness for information (Kristjanson, Chalmers, & Woodgate, 2004). In addition, this information should be given to patients when they feel ready, as well as during different treatment stages (Kristjanson et al., 2004). In the current study, participants suggested that one or two months after starting treatment may be an optimal time to share the information presented in the FOL Information Kit with patients. At this point, patients are more accepting of their diagnosis and display a readiness to receive more tailored information. When patients are involved in planning their cancer treatment and know what to expect, they can reach a state of acceptance (Jakobsson, Horvath, & Ahlberg, 2005). Addressing the informational needs of YAs while they are in active care will lessen their overall distress, improve their cancer experience, and empower patients to re-enter normal life upon completion of their cancer journey. Dedicated attention to programmatic initiatives is required to ensure the appropriate delivery of supportive care mechanisms to address these needs (Gupta, Edelstein, Albert-Green, & D’Agostino, 2013).

Implications for Practice

The Vo-Pak program could be optimized by re-engaging healthcare professionals to implement the recommendations of the participants (Scheirer, 2005). Re-engaging healthcare professionals, as well as helping them to understand the perceived benefits to patients, may help them to be more motivated and better equipped to deliver the Vo-Pak and explain its contents. Recipients of the Vo-Pak would become more aware of its components and more likely to benefit from them. Awareness can also be achieved indirectly through advertisements, including a more informative social media presence (e.g., YouTube, Facebook) and in detailed pamphlets and advertisements within clinical settings.

Participants in the current study stressed the need for a Vo-Pak champion to deliver time-sensitive information, explain the Vo-Pak’s contents, and help patients connect to peers. A champion can be invaluable in the success of tangible support programs and is the most frequently cited factor for ensuring ongoing delivery of program objectives (Treadgold & Kuperberg, 2010). A champion could have assisted by directing participants toward the VOBOC website, which contains a list of all its events; the CancerFightClub card, an online resource available to YAs; and other online resources. Accessing resources is paramount for receiving information about cancer and connecting to professionals and peer support groups (Klemm et al., 2003). As such, measures should be taken to assign members of the multidisciplinary team to champion the mission of VOBOC and promote the various VOBOC-led activities. Although VOBOC does not provide medical information and believes that members of the healthcare team should provide this information, findings from the current study suggest that participants have a number of unmet needs related to their medical treatment. A need exists to provide YAs with greater medical information. VOBOC is exploring ways to support the provision of such general information without providing specific information tailored to a patient’s diagnosis or unique situation. One suggestion may include inserting leaflets already provided by the hospital into the Vo-Pak to enhance the provision of medical information. VOBOC is also looking into how to better communicate the needs of the YA population to members of the healthcare team, with the goal of improving the quality of YA cancer care. Collectively, these clinical implications may serve to help refine and improve valuable resources like the Vo-Pak.

Implications for Research

This qualitative study may aid future investigations in evaluating programs like Vo-Pak by pinpointing key areas for exploration (e.g., exploring the users’ experience, identifying issues related to implementation and evaluation, investigating areas for enhancement, preparing for large-scale evaluations). The current authors’ next step is to conduct a multisite evaluation of the Vo-Pak using a survey design across all Vo-Pak sites to better understand the needs of YAs and their perceptions of the Vo-Pak, as well as to prioritize further directions (e.g., need for medical information, peer support, timely delivery of the Vo-Pak). Simultaneously, the current authors are seeking to develop and evaluate a YA peer support and networking program. Because only a handful of support interventions are available to meet the needs of YAs, the current study showcases the first step toward evaluating a tangible support service aimed at addressing these unmet needs and helping to improve the quality care gap. The current authors encourage researchers to partner with community organizations to evaluate existing programs in their local areas.

Conclusion

Participants positively perceived the Vo-Pak and considered it to be a welcoming, ready-to-go, and timely package. To meet the needs of YAs, two findings stand out: (a) strengthen the Vo-Pak program by promoting the backpack, its contents, and purposes and (b) enhance networking opportunities among YAs with cancer. Doing so would add to the overarching goal of providing comprehensive person-centered care and services to underserved segments of the cancer population.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Doreen Edward, their community partner and the founder of Venturing Out Beyond Our Cancer (VOBOC) who helped facilitate access to the study site, provided insights on the young adult population, and offered information on services rendered by VOBOC.

References

Albritton, K., & Bleyer, W.A. (2003). The management of cancer in the older adolescent. European Journal of Cancer, 39, 2584–2599. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2003.09.013

Aubin, S., Rosberger, Z., Petr, K., & Gerald, B. (2011). Reporting on the clinical utility of a coping skills intervention program for AYAC: What have we learned thus far [Poster abstract]. Psycho-Oncology, 20(Suppl. 2), 199. doi:10.1002/pon.2078

Barrera, M., Damore-Petingola, S., Fleming, C., & Mayer, J. (2006). Support and intervention groups for adolescents with cancer in two Ontario communities. Cancer, 107(Suppl. 7), 1680–1685. doi:10.1002/cncr.22108

Beale, I.L., Kato, P.M., Marin-Bowling, V.M., Guthrie, N., & Cole, S.W. (2007). Improvement in cancer-related knowledge following use of a psychoeducational video game for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 263–270. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.006

Bingen, K., & Kupst, M.J. (2010). Evaluation of a survivorship educational program for adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Cancer Education, 25, 530–537. doi:10.1007/s13187-010-0077-y

Canada, A.L., Schover, L.R., & Li, Y. (2007). A pilot intervention to enhance psychosexual development in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 49, 824–828. doi:10.1002/pbc.21130

Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. (2015). Canadian cancer statistics 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%2…

Colaizzi, P.F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In R.S. Valle & M. King (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology (pp. 48–71). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Curran, M.S., Saylor, E., & Portrey, A. (2012). Young adults embracing survivorship: YES program [Poster abstract]. Psycho-Oncology, 21(Suppl. 1), 117–118. doi:10.1111/j.1099-1611.2011.03029_1.x

D’Agostino, N.M., Penney, A., & Zebrack, B. (2011). Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer, 117(Suppl. 10), 2329–2334. doi:10.1002/cncr.26043

De, P., Ellison, L.F., Barr, R.D., Semenciw, R., Marrett, L.D., Weir, H.K., . . . Grunfeld, E. (2011). Canadian adolescents and young adults with cancer: Opportunity to improve coordination and level of care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183, E187–E194. doi:10.1503/CMAJ.100800

Dyson, G.J., Thompson, K., Palmer, S., Thomas, D.M., & Schofield, P. (2012). The relationship between unmet needs and distress amongst young people with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 75–85. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-1059-7

Fernandez, C.V., & Barr, R.D. (2006). Adolescents and young adults with cancer: An orphaned population. Paediatrics and Child Health, 11, 103–105.

Gupta, A.A., Edelstein, K., Albert-Green, A., & D’Agostino, N. (2013). Assessing information and service needs of young adults with cancer at a single institution: The importance of information on cancer diagnosis, fertility preservation, diet, and exercise. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 2477–2484. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1809-4

Jakobsson, S., Horvath, G., & Ahlberg, K. (2005). A grounded theory exploration of the first visit to a cancer clinic—Strategies for achieving acceptance. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 9, 248–257. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2004.08.005

Kerr, L.M., Harrison, M.B., Medves, J., & Tranmer, J. (2004). Supportive care needs of parents of children with cancer: Transition from diagnosis to treatment [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31, E116–E126. doi:10.1188/04.ONF.E116-E126

Klemm, P., Bunnell, D., Cullen, M., Soneji, R., Gibbons, P., & Holecek, A. (2003). Online cancer support groups: A review of the research literature. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 21, 136–142. doi:10.1097/00024665-200305000-00010

Kristjanson, L.J., Chalmers, K.I., & Woodgate, R. (2004). Information and support needs of adolescent children of women with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31, 111–119. doi:10.1188/04.ONF.111-119

Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, R., Nousiainen, E.M., Rytilahti, M., Seppänen, P., Vaattovaara, R., & Jämsä, T. (2001). Coping with the onset of cancer: Coping strategies and resources of young people with cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 10, 6–11. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00243.x

Levy, J. (2002). Financial assistance from national organizations for cancer survivors. Cancer Practice, 10, 48–52. doi:10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.101004.x

Lockhard, I.A., & Berard, R.M.F. (2001). Psychological vulnerability and resilience to emotional distress: A focus group study of adolescent cancer patients. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 13, 221–229. doi:10.1515/IJAMH.2001.13.3.221

McDowell, M.E., Occhipinti, S., Ferguson, M., Dunn, J., & Chambers, S.K. (2010). Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 508–516. doi:10.1002/pon.1604

Millar, B., Patterson, P., & Desille, N. (2010). Emerging adulthood and cancer: How unmet needs vary with time-since-treatment. Palliative and Supportive Care, 8, 151–158. doi:10.1017/S1478951509990903

Nelson, C. (2011). The financial hardship of cancer in Canada: A literature review. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/MB/get%20involved/take%20action…

Nordstrom, D.G. (1988). The autosyringe backpack for children with cancer: A device that permits mobility. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 5, 77–86. doi:10.1080/J003v05n02_09

Olsen, P.R., & Harder, I. (2011). Caring for teenagers and young adults with cancer: A grounded theory study of network-focused nursing. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15, 152–159. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2010.07.010

Palmer, S., Mitchell, A., Thompson, K., & Sexton, M. (2007). Unmet needs among adolescent cancer patients: A pilot study. Palliative and Supportive Care, 5, 127–134. doi:10.1017/s1478951507070198

Patterson, P., Millar, B., Desille, N., & McDonald, F. (2012). The unmet needs of emerging adults with a cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study. Cancer Nursing, 35, E32–E40. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822d9105

Pentheroudakis, G., & Pavlidis, N. (2005). Juvenile cancer: Improving care for adolescents and young adults within the frame of medical oncology. Annals of Oncology, 16, 181–188. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi036

Ramphal, R., D’Agostino, N.M., Klassen, A., McLeod, M., De Pauw, S., & Gupta, A. (2011). Practices and resources devoted to the care of adolescents and young adults with cancer in Canada: A survey of pediatric and adult cancer treatment centers. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 1, 140–144. doi:10.1089/jayao.2011.0023

Robison, L.L. (2011). Opportunities and challenges of establishing a nationwide strategy for adolescents and young adults in Canada with cancer: Impressions from the Toronto workshop. Cancer, 117(Suppl. 10), 2351–2354. doi:10.1002/cncr.26041

Scheirer, M.A. (2005). Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. American Journal of Evaluation, 26, 320–347. doi:10.1177/1098214005278752

Schultz, D.M., & Mir, M. (2012). Cancer180: Because when cancer strikes, life does a 180 [Paper abstract]. Psycho-Oncology, 21(Suppl. 1), 7. doi:10.1111/j.1099-1611.2011.03029_1.x

Smith, S., Davies, S., Wright, D., Chapman, C., & Whiteson, M. (2007). The experiences of teenagers and young adults with cancer—Results of 2004 conference survey. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 11, 362–368. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2006.11.002

Taylor, R.M., Fern, L., Whelan, J., Pearce, S., Grew, T., Millington, H., . . . Gibson, F. (2011). “Your place or mine?” Priorities for a specialist teenage and young adult (TYA) cancer unit: Disparity between TYA and professional perceptions. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 1, 145–151. doi:10.1089/jayao.2011.0037

Taylor, R.M., Pearce, S., Gibson, F., Fern, L., & Whelan, J. (2012). Developing a conceptual model of teenage and young adult experiences of cancer through meta-synthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 832–846. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.011

Treadgold, C.L., & Kuperberg, A. (2010). Been there, done that, wrote the blog: The choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4842–4849. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0516

Ussher, J., Kirsten, L., Butow, P., & Sandoval, M. (2006). What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 2565–2576. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.034

Venturing Out Beyond Our Cancer. (2014). About us. Retrieved from http://voboc.org/about-us

Wicks, L., & Mitchell, A. (2010). The adolescent cancer experience: Loss of control and benefit finding. European Journal of Cancer Care, 19, 778–785. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01139.x

Zebrack, B. (2009). Information and service needs for young adult cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 17, 349–357. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0469-2

Zebrack, B., Bleyer, A., Albritton, K., Medearis, S., & Tang, J. (2006). Assessing the health care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer, 107, 2915–2923. doi:10.1002/cncr.22338

Zebrack, B., & Butler, M. (2012). Context for understanding psychosocial outcomes and behavior among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 10, 1151–1156.

Zebrack, B., Chesler, M.A., & Kaplan, S. (2010). To foster healing among adolescents and young adults with cancer: What helps? What hurts? Supportive Care in Cancer, 18, 131–135. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0719-y

Zebrack, B.J. (2011). Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer, 117(Suppl. 10), 2289–2294. doi:10.1002/cncr.26056

Zebrack, B.J., Block, R., Hayes-Lattin, B., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Meeske, K.A., . . . Cole, S. (2013). Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer, 119, 201–214. doi:10.1002/cncr.27713

About the Author(s)

Wazneh is a nurse clinician at the Montreal Children’s Hospital in Quebec, and Tsimicalis is an assistant professor and Loiselle is an associate professor, both in the Ingram School of Nursing at McGill University in Montreal, all in Canada. This research was funded by a grant from the Quebec Nursing Intervention Research Network in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Tsimicalis and Loiselle contributed to the conceptualization and design. Wazneh completed the data collection. Tsimicalis provided statistical support. Wazneh, Tsimicalis, and Loiselle contributed to the analysis and manuscript preparation. Wazneh can be reached at laila.wazneh@mail.mcgill.ca, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted March 2015. Accepted for publication June 7, 2015.