The Ars Moriendi Model for Spiritual Assessment: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation

Purpose/Objectives: To explore nurses’ and physicians’ experiences with the ars moriendi model (AMM) for spiritual assessment.

Design: Convergent, parallel, mixed-methods.

Setting: Palliative home care in Belgium.

Sample: 17 nurses and 4 family physicians (FPs) in the quantitative phase, and 19 nurses and 5 FPs in the later qualitative phase.

Methods: A survey was used to investigate first impressions after a spiritual assessment. Descriptive statistics were applied for the analysis of the survey. In a semistructured interview a few weeks later, nurses and physicians were asked to describe their experiences with using the AMM. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and qualitatively analyzed. Quantitative and qualitative results were compared to see whether the findings were confirmative.

Main Research Variables: The survey assessed the feasibility of the AMM for use in palliative home care, whereas the semistructured interviews collected in-depth descriptions of healthcare providers’ (HCPs’) experiences with the AMM.

Findings: The AMM was perceived as valuable. Many patients shared their wishes and expectations about the end of life. Most HCPs said they felt that the patient-provider relationship had been strengthened as a result of the spiritual assessment. Almost all assessments raised new issues; however, many dyads had informally discussed spiritual issues before.

Conclusions: The current study suggests that HCPs believe that the AMM is a useful spiritual assessment tool. Guided by the model, HCPs can gather information about the context, life story, and meaningful connections of patients, which enables them to facilitate person-centered care.

Implications for Nursing: The AMM appears to be an important tool for spiritual assessment that can offer more insight into patients’ spirituality and help nurses to establish person-centered end-of-life care.

Jump to a section

Researchers from all over the world have contributed to a growing understanding of spiritual care, providing a solid evidence base. Although much has yet to be learned, this evidence, combined with motivation and educational support, enables nurses to develop best practices concerning the spiritual dimension of caring (Cockell & McSherry, 2012). Spiritual well-being in patients with advanced illness is strongly associated with quality of life (Balboni et al., 2010). Healthcare providers (HCPs) (e.g., oncology nurses) view spirituality as an important aspect of palliative care, and the majority of HCPs think that patients undergoing palliative care can benefit from the regular provision of spiritual care (Phelps et al., 2012).

Some sources suggest that nurses and physicians should perform spiritual screening as part of patients’ routine history-taking (Puchalski et al., 2009). HCPs should also identify any spiritual problems and develop a plan of care. Worldwide, efforts are being made to incorporate spiritual care into the education of nurses and physicians (Lovanio & Wallace, 2007; Nicol, 2012; O’Shea, Wallace, Griffin, & Fitzpatrick, 2011). However, in clinical care, the provision of spiritual care remains difficult. Although a majority of patients with advanced cancer perceive spirituality to be a relevant issue, 72% of patients with advanced cancer report that their spiritual needs are minimally or not at all supported by HCPs (Balboni et al., 2007). Barriers that stand in the way of HCPs properly addressing patients’ spiritual needs include a lack of education, confidence, and the right vocabulary; a belief that spiritual care is someone else’s responsibility; and various influences of secularism and diversity in society (Molzahn & Sheilds, 2008; Ronaldson, Hayes, Aggar, Green, & Carey, 2012; Vermandere et al., 2011).

Spiritual assessment is an increasingly important issue for nursing practice; however, the range of reliable and valid quantitative instruments for use in clinical practice is limited (Draper, 2012). More than 35 spiritual assessment tools are available in palliative care, but many of them have been developed for research purposes (Monod et al., 2011). Lucchetti, Bassi, and Lucchetti (2013), who reviewed the literature to compare the most commonly used instruments, recommended individualizing the use of each instrument to each patient.

The ars moriendi model (AMM) meets many of the requirements of a spiritual assessment tool in palliative care (Vermandere et al., 2013). This model has its roots in the Middle Ages; in the 15th century, it was handed down in its most popular form in a book of 11 block prints. The book features five temptations that are presented to the dying person: the loss of faith, the loss of one’s confidence in salvation, the hanging on to temporal affairs, the inability to deal with pain and suffering, and pride. These temptations are typically depicted as devils and other diabolic creatures. Fortunately, the dying are also supported by angels and saints who inspire them to focus on virtues, such as faith, hope, patience, and humility. The aim of this medieval model is clear: Preparing to die is the final battle between the powers of good and evil, and those who die are forced to make the choice between heaven and hell. Since the 15th century, some profound changes have taken place in Western culture that make this ancient model no longer applicable to modern society. However, the model deals with five themes that still play a crucial role at the end of life. Carlo Leget, professor of ethics of care and spiritual counseling at the University of Humanistic Studies in the Netherlands, along with Dutch general practitioners, updated this model to better reflect modern culture and challenges and to take a spiritual history at the end of life (Leget, 2003, 2007, 2008). The dying person no longer has to choose between good and evil, but instead is situated somewhere in between, feeling the tension of both poles. In the middle of these tension fields is the concept of inner space, which is not a matter that can be addressed by HCPs alone. Leget (2007) defined inner space as “an important precondition for good palliative care, as a goal to aim for in the hearts and minds of all parties involved, and as a sign that good care actually is given” (p. 315). The open structure and diamond shape of the model provide flexibility and spontaneity in the communication about spirituality. The questions of the model are formulated in spoken language (Leget, 2007), and five tension fields are presented (i.e., autonomy, pain control, attachment and relations, guilt and evil, and the meaning of life). These five themes play a crucial role in the dying process, assisting the patient with making his or her own choices and facilitating communication among the patient, family members, and caregivers (Leget, 2007). HCPs evaluated the AMM as being useful for spiritual assessment in a pilot study, and patients undergoing palliative care were stimulated by the questions in the model to think about their spiritual needs and resources (Vermandere et al., 2013).

However, very little is known about how HCPs feel about using the AMM in clinical practice. The current study aims to investigate the experiences of nurses and physicians using the AMM for spiritual assessment in palliative home care.

Methods

The current authors followed a convergent, parallel, mixed-methods design, which is likely the most familiar of the mixed-methods strategies (Creswell, 2013). In this approach, a researcher collects quantitative and qualitative data, analyzes them separately, and then compares the results to see if the findings confirm or refute each other. The key assumption of this approach is that quantitative and qualitative data provide different types of information, but together they yield results that should be the same. This approach builds off the multitrait, multimethod analysis developed by Campbell and Fiske (1959), who felt that a psychological trait could best be understood by gathering different forms of data. The current authors collected quantitative data through a survey designed to gather first impressions after the spiritual assessment. Semistructured interviews were conducted a few weeks later to investigate participants’ experiences with the AMM more in depth and the changes in healthcare relationships that occurred in the weeks after the spiritual assessment. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals of KU Leuven in Belgium.

Quantitative Phase

Participants and recruitment: Nurses and family physicians (FPs) allocated to the intervention arm of a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) (Vermandere, Warmenhoven, Van Severen, De Lepeleire, & Aertgeerts, in press) participated in the current study, which can be viewed as a spinoff of the RCT. The aim of the RCT was to investigate the effect of a structured spiritual assessment on the spiritual well-being of patients undergoing palliative home care. The RCT study began with the recruitment of nurses and FPs from December 2012 to March 2013. Nurses were invited by their organization (the White Yellow Cross, a Belgian home nursing organization) via email, whereas FPs were invited following presentations about the study at regional scientific meetings. To be eligible for the study, HCPs had to be registered as either a home nurse or an FP, as well as speak Dutch. HCPs who had participated in the pilot study involving the AMM were excluded.

The HCPs allocated to the intervention arm of the RCT were required to attend one training session; sessions were offered between February and May 2013 and organized in groups of no more than 25 HCPs. Participants reflected on spirituality in health care in the first part of the training session, then explored spirituality specifically in the setting of palliative care in the second part. The AMM was presented, clarified, and practiced in the third part of the training session, followed by the flow chart of patient inclusion, spiritual assessment, and outcome measurement for the RCT in the fourth part.

The enrollment of patients by HCPs occurred between April and October 2013. Patients diagnosed with a progressive, life-threatening disease were eligible for the study. The participants needed to remain in the study for at least six weeks to complete the protocol. Consequently, patients whose prognosis was estimated by their treating physician to be less than two months were excluded. In addition, the patients had to speak Dutch, as well as be competent, aged 18 years or older, and aware of the palliative diagnosis. Patients with any active major psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment were excluded.

Nurses and FPs were free to discuss the study with the patients. After obtaining verbal agreement from each patient, the current authors reviewed his or her eligibility to participate. The current authors later organized a meeting to further explain the study to patients; written informed consent was obtained at the meeting from patients who elected to participate.

HCPs in the intervention arm used the AMM for a spiritual assessment at each participating patient’s home. However, HCPs who had been assigned to the control arm of the study did not receive a model for spiritual assessment, and they provided usual care to their patients undergoing palliative care. The remainder of the study procedure was identical to that of the intervention arm. All outcome scales for the RCT were completed on paper by patients at the time of pre- and postmeasurements (i.e., one week before and three to four weeks after the spiritual assessment) during home visits by the current authors.

Study design: The current study, an offshoot of the RCT, focuses on the experiences of the 22 nurses and physicians in the RCT’s intervention arm. They were invited to complete a survey immediately after the spiritual assessment to investigate their feelings concerning the use of the AMM, as well as the course and content of the spiritual assessment. This survey was developed based on the current authors’ previous experiences with the AMM. Participants were asked to respond using five-point Likert-type scales. The survey concluded with the option to write down other remarks or suggestions.

Data analysis: Descriptive statistics were applied for analysis of the survey because the sample (N = 22) was too small for further statistical analysis; comparison between nurses (n = 18) and FPs (n = 4) was not possible for the same reason. The current authors dichotomized the results from the survey to facilitate the interpretation. Scores 1 and 2 on the Likert-type scale were seen as disagreement with the theorem, score 3 was seen as neutral, and scores 4 and 5 were interpreted as agreement.

Qualitative Phase

Participants and recruitment: All HCPs who completed the survey from the quantitative phase of the current study were invited to participate in a semistructured telephone interview four to six weeks later. All of the interviews were led by one of the current authors who was not involved in the design or analysis phase of the study. Three additional HCPs from the intervention arm of the RCT were invited to participate in a telephone interview to ensure that data saturation was achieved.

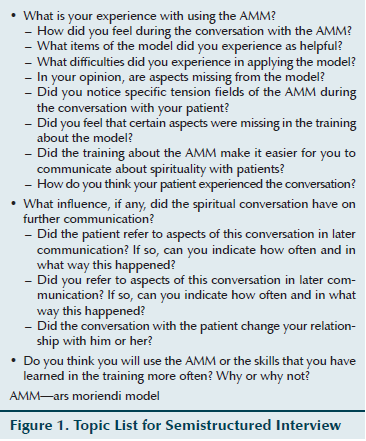

Study design: The current authors performed semistructured interviews. The main topics of the interview were how caregivers had experienced the AMM as a spiritual assessment tool, whether it had helped them to communicate about spirituality, and whether the assessment was followed by additional conversations about spirituality (see Figure 1). However, the interviewer used the topic list only as a suggested interview structure and was free to elaborate on other topics.

Data analysis: All interviews were digitally audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and entered into NVivo, version 9, software to assist with data analysis. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the interviews (Braun & Clarke, 2006). An initial codebook, based on the themes of the interview topic list, was developed. One of the current authors used an inductive stepwise approach to analyze the data (Bruyninckx, Van den Bruel, Hannes, Buntinx, & Aertgeerts, 2009). Issues of interest were marked in the data, labeled, and compared and contrasted with other interview excerpts. Another author independently analyzed all of the interviews using this codebook, and marked and labeled the issues of interest. New themes were added to the codebook to better reflect themes that emerged, and all interviews were analyzed again using the final version of the codebook. Data saturation, defined as the identification of no new codes in the last two interviews, was the objective.

Results

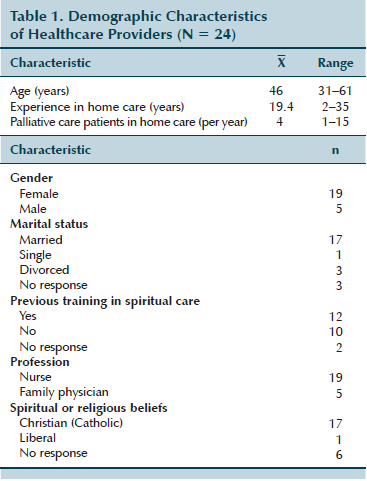

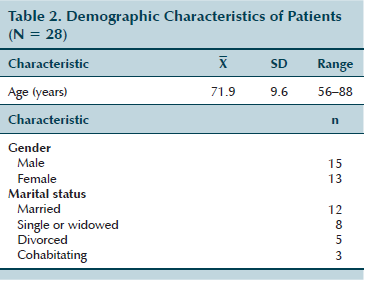

Seventeen nurses and four FPs completed the survey. One of the nurses returned two surveys because she performed a spiritual assessment on two patients. Twenty-four HCPs (the 21 HCPs who completed the survey and three additional HCPs) participated in the semistructured interviews. One interview was not properly audio recorded and could not be used in the analysis. Demographic data of the 24 participating HCPs are shown in Table 1, and demographic data of their patients are shown in Table 2.

Quantitative Phase

Sixteen of the 21 HCPs said they felt comfortable with the content of the AMM, and 18 said they felt calm and at ease during the spiritual assessment. Initiating the spiritual conversation was thought of as easy by 19 HCPs and as spontaneous by 18 HCPs. Only two nurses had the impression that the conversation was forced or unnatural. Most tension fields from the AMM were discussed during the assessments. Eighteen HCPs perceived the AMM as a valuable tool in palliative care, but 16 said they would have addressed spiritual issues with their patients without the prompting of the study. Fifteen HCPs reported feeling that the healthcare relationship had been strengthened as a result of the spiritual assessment. Twenty HCPs said they would continue to talk about spirituality with their future patients undergoing palliative care, and 19 said they would recommend the model to their colleagues.

Qualitative Phase

Useful spiritual assessment tool: The content and questions of the AMM supported most HCPs in their history-taking. The AMM made finding the right words easier and helped them to structure the conversation. However, most HCPs said they preferred to divide spiritual assessment into several spontaneous and shorter moments integrated into daily care rather than perform an assessment apart from other conversations.

I think it’s a nice extra tool that helps me to carry on these types of conversations. Not that they weren’t taking place before, but perhaps it happens more consciously now or with more attention for different “fields” in the conversations. So I, in fact, have found it to be a fine tool. (HCP 2129)

Initiating the spiritual assessment felt unnatural to many HCPs, mostly because they were not used to doing so. However, once the conversation had started, they experienced it as natural and smooth. Most HCPs said they were comfortable during the course of the assessment.

Yes, in the beginning, I did indeed feel a bit uncomfortable that I had to bother her with such questions, but after a while she was somewhat more relaxed, and then I was feeling better too. (HCP 11111)

Yes, it was easy. During the procedure, she even told me I should go get something to drink and a cookie. It was more like a coffee break, if you know what I mean. (HCP 11118)

Most HCPs succeeded in performing the assessment, provided that the patient was willing to talk about spirituality at that particular moment. Observing inner space (i.e., open-minded attitude) in the patient and the family caregiver and respecting silence whenever appropriate were important conditions for spiritual assessment. A few HCPs said they felt that the patient did not have inner space at the time of the conversation; those assessments were more difficult than others. In addition, HCPs stressed the importance of compassionate presence as a condition for talking about spirituality.

The most difficult part for me was that I had to confront him with it, whereas he preferred not to dwell on it at that time. It was a really difficult moment for him, you know. He didn’t really cry, but you could feel that it went very deep. On the other hand, I do also think that it was good for him. (HCP 11104)

Before, I always had the feeling that we had to keep talking, but now I know that listening is also very important and that those silent moments are really okay. (HCP 11093)

More insight into spiritual needs and resources: The AMM helped some HCPs to overcome their insecurity about performing a spiritual assessment. The five tension fields of the model helped the HCPs to know what issues should be discussed. Most HCPs started the conversation with a screening question. Depending on the patients’ answers, HCPs chose to explore one or more tension fields in depth.

I benefited enormously from the process myself because it is now easier for me to make such things a subject of discussion. For me, it has been a handy model to work with, and it has helped me to dare to discuss things with patients more in that direction. (HCP 1171)

So it does also depend to a certain extent on the patient’s personality. What does he permit? Perhaps it is not equally easy for everyone to talk about certain things. (HCP 2114)

Throughout the assessment, HCPs gained more insight into their patients’ spiritual needs and resources. They got to know their patients better, and patients often shared important wishes and expectations about the end of life. Most HCPs described working with the AMM as a chance to discuss new themes that probably would not have been raised without this history-taking.

In that conversation, one of the things that came up was that he still wants to visit his daughter’s grave one more time. (HCP 1159)

It also gave him the opportunity to say a number of things that he had previously not yet talked about. (HCP 2114)

Patients in their context and life stories: Although none of the patients expressed an explicit need to talk about spirituality, many HCPs experienced the spiritual assessment as meaningful. The AMM not only stimulated patients to think about their spiritual well-being, but also enabled HCPs to learn a lot about the context, connections, and relationships of the patient (e.g., role of religion, family relations, inner resources, views of afterlife).

He also said himself that he was satisfied . . . that, for once, he had talked about it. On all the previous occasions, he had always said that he did not feel the need, that it wasn’t necessary for him. . . . It was, nevertheless, quite emotional. (HCP 11135)

She then did talk about it, and she found it quite hard to do, to discuss about her father and mother. Then she did become a bit emotional. (HCP 11106)

Many patients spontaneously told their life story in response to the questions of the AMM. HCPs discovered a huge need in patients to share their stories, as well as a lot of gratitude for their taking the time to listen. Almost all spiritual history-takings raised new issues; however, many dyads had informally discussed spiritual issues before.

It was, in fact, the whole story of his life that that man told me, and that helps me to place that man in a certain context, and that is a wealth of information that you, as a physician, will continue to use further in the future whenever you again become more closely involved in counseling him. (HCP 2129)

Person-centered care: Many HCPs said they felt more closely connected to their patients after the spiritual assessment. They also noted that their patients had more confidence and were more open-hearted toward them. HCPs who did not notice changes were the ones who already had a close relationship with their patients before the assessment.

Yes, I think that, due to the fact that we had that conversation, perhaps a kind of foundation was laid, which might perhaps make it easier for us on a future occasion to return to a number of things, should that be necessary. (HCP 2129)

In fact, I always had a good relationship with that patient. I don’t think that that changed anything in that respect. The relationship was already there. (HCP 11117)

The information gathered about patients’ spiritual needs, resources, wishes, and expectations enabled HCPs to provide good quality, person-centered end-of-life care. All HCPs acknowledged the lack of spiritual care in daily practice and noted that the AMM helped them to organize palliative home care with respect to the spiritual dimension of their patients.

It is a general fact that much too little attention is given to the experience and the thoughts of the people in their final phase of life. We are busy with everything surrounding the event and also with the children, making all the arrangements for caretakers, etc., and all with the best of intentions, but, in fact, questions such as, “How are you doing now?” or, “What do you think about this now?” are not being asked. (HCP 11152)

But I think that this is, in fact, the most important thing that I gained from that conversation: namely, that I now understand the context and that life story. And I hope that in the future, if that becomes difficult, this understanding will enable me to help that man better. (HCP 2129)

Discussion

Comparison of Results

The interviews revealed that the AMM can be a useful spiritual assessment tool. This finding is confirmed by the survey in which 19 HCPs noted that the AMM could make a positive difference in spiritual conversations in palliative care. Almost all HCPs rated the assessment as spontaneous in the early quantitative phase. However, many HCPs mentioned during the interview that integrating a spiritual assessment into daily care and dividing it up into several shorter moments would be more spontaneous than the conversation as planned for the trial. The survey further showed that only two nurses indicated that the assessment was forced or unnatural. This finding is confirmed by the interviews, in which many HCPs indicated that they experienced the start of the assessment as a bit forced; however, most conversations continued naturally and were fluid. Only three nurses did not feel calm, according to results of the survey. The other 18 HCPs did feel calm, and the current authors learned from the interviews that the AMM helped many HCPs to overcome their uncertainty and to feel at ease. In addition, many HCPs indicated in the survey, as well as during the interview, that the healthcare relationship had been strengthened following the spiritual assessment. Consequently, the conclusion can be drawn that the findings of the quantitative and qualitative parts of the study are confirmative.

Strengths and Limitations

The findings of the quantitative and qualitative parts of the current study are confirmative, which is a strength. In addition, information about the HCPs’ first impressions after the spiritual assessment is supplemented by information about changes in the healthcare relationship in the weeks following that conversation. Data saturation was achieved during the analysis of the interviews, which indicates that the overview of the HCPs’ experiences with the AMM is robust. Because trials in palliative home care are rather scarce, this study makes a substantive contribution to the understanding and organization of spiritual assessment in a palliative homecare setting.

However, this study also has certain limitations. The study sample for the survey was small, which means that no statistical analysis could be carried out on the data. The current authors were able to give only descriptive results of the quantitative data, and a comparison between nurses and physicians was not possible. All HCPs and patients in this trial agreed to participate in a study concerning communication at the end of life, and, therefore, generalizing the findings to HCPs or patients who are less interested in improving patient-provider communication may not be possible. In addition, these findings may not be applicable in other healthcare settings (e.g., inpatient settings). The study sample was predominantly Christian, so the results must be interpreted with caution when applying them to populations with other belief systems. The current study also focused on HCPs’ views and did not take into account patients’ or family caregivers’ experiences with the AMM. Knowing how patients undergoing palliative care and their family caregivers perceive a spiritual history-taking guided by the AMM would be valuable.

Comparison With the Literature

Developing criteria for clinical instruments for spiritual assessment is complex, and no consensus about these criteria exists. The most commonly used instruments developed for this purpose were compared by Lucchetti et al. (2013) using 16 criteria, nine of which were related to religious affiliation (e.g., religious affiliation, religious attendance, religious coping). Because the AMM contains just one question that is explicitly about religion, it would probably score low according to the criteria used by Lucchetti et al. (2013). However, instruments for spiritual assessment are not tick-box exercises; instead, they serve as guidance for a personal and intimate conversation between HCPs and patients. In addition, religion can be a part of spirituality, but spirituality is much broader than religion. Despite the AMM’s likely scoring low according to Lucchetti et al.’s (2013) criteria, the current study demonstrates that the AMM can, in fact, make a positive difference in spiritual conversations.

Although such instruments are an easy method for addressing spiritual issues, they are by no means the only approach. Some HCPs may use their own methods to achieve the same or better results (Lucchetti et al., 2013). In addition, traditional assessment approaches may be ineffective with patients who are uncomfortable with spiritual language or otherwise hesitant to overtly discuss spirituality. Alternative approaches (e.g., implicit spiritual assessment) may be more valid with such patients (Hodge, 2013).

Most patients with advanced cancer never receive any form of spiritual care from their oncology nurses or physicians (Balboni et al., 2012). Spiritual distress experienced by patients with cancer may be underaddressed because of HCPs’ lack of confidence and role uncertainty (Kristeller, Zumbrun, & Schilling, 1999). The AMM can help HCPs to overcome their incertitude about performing a spiritual assessment, and these instruments should be implemented in nursing and medical curricula.

The information that HCPs in the current study gathered about their patients’ spiritual needs and resources enabled them to provide good quality, person-centered end-of-life care. Similarly, others suggest that spiritual needs should be addressed on the basis of a patient-centered approach to care (Puchalski et al., 2009; Puchalski & Romer, 2000). HCPs using the AMM discovered a huge need in patients to share the story of their life, their context, and their meaningful connections, as well as their wishes and expectations for end-of-life care. Patients with advanced illness want the medical team to address their spirituality as part of medical care (El Nawawi, Balboni, & Balboni, 2012). Sixty-six of 100 patients indicated that they would want their physicians to ask about their spiritual beliefs if they were to become gravely ill (Ehman, Ott, Short, Ciampa, & Hansen-Flaschen, 1999). In addition, 709 (77%) of 921 patients seen in a family practice setting said they would want to have spiritual discussions with their physicians if they were facing life-threatening illness (McCord et al., 2004). The majority of these patients said they thought that these spiritual discussions would better enable their physicians to encourage realistic hope and to give better medical advice, which, together, may lead to a change in the medical decision-making (McCord et al., 2004). Likewise, the AMM helped the nurses and physicians in the current study to coordinate palliative home care that reflected the spiritual dimension in their patients’ lives.

Implications for Research

The AMM has shown its potential for spiritual assessment in palliative home care for nurses and physicians. More research is needed to see if these findings are confirmed in other settings (e.g., hospital, hospice), with other caregivers (e.g., volunteer, physiotherapist), and in populations with other belief systems. A more in-depth investigation of patients’ and family caregivers’ experiences with instruments for spiritual history-taking would be valuable. Ultimately, a tool for spiritual assessment must be integrated into nursing and medical education, but, at the same time, the naturalness of the compassionate human connection in which patient-provider communication normally occurs must be preserved.

Conclusion

The AMM can help HCPs to overcome their uncertainty about spiritual assessment. The five tension fields of the model are perceived as a helpful guide to discussing certain themes at the end of life, and they can lead to more insight into patients’ spiritual needs and resources. Aided by this model, HCPs can gather information about patients’ context, life story, and meaningful connections, which enables them to organize person-centered palliative home care with respect to the spiritual dimension.

References

Balboni, M.J., Sullivan, A., Amobi, A., Phelps, A.C., Gorman, D.P., Zollfrank, A., . . . Balboni, T.A. (2012). Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 461–467. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6443

Balboni, T.A., Paulk, M.E., Balboni, M.J., Phelps, A.C., Loggers, E.T., Wright, A.A., . . . Prigerson, H.G. (2010). Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: Associations with medical care and quality of life near death. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27, 445–452. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005

Balboni, T.A., Vanderwerker, L.C., Block, S.D., Paulk, M.E., Lathan, C.S., Peteet, J.R., & Prigerson, H.G. (2007). Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 555–560. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruyninckz, R., Van den Bruel, A., Hannes, K., Buntinx, F., & Aertgeerts, B. (2009). GPs’ reasons for referral of patients with chest pain: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 10, 55. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-10-55

Campbell, D.T., & Fiske, D.W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81–105. doi:10.1037/h0046016

Cockell, N., & McSherry, W. (2012). Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of published international research. Journal of Nursing Management, 20, 958–969. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01450.x

Creswell, J.W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Draper, P. (2012). An integrative review of spiritual assessment: Implications for nursing management. Journal of Nursing Management, 20, 970–980. doi:10.1111/jonm.12005

Ehman, J.W., Ott, B.B., Short, T.H., Ciampa, R.C., & Hansen-Flaschen, J. (1999). Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Archives of Internal Medicine, 159, 1803–1806. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803

El Nawawi, N.M., Balboni, M.J., & Balboni, T.A. (2012). Palliative care and spiritual care: The crucial role of spiritual care in the care of patients with advanced illness. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 6, 269–274. doi:10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283530d13

Hodge, D.R. (2013). Implicit spiritual assessment: An alternative approach for assessing client spirituality. Social Work, 58, 223–230. doi:10.1093/sw/swt019

Kristeller, J.L., Zumbrun, C.S., & Schilling, R.F. (1999). ‘I would if I could’: How oncologists and oncology nurses address spiritual distress in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 8, 451–458. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<451::AID-PON422>3.0.CO;2-3

Leget, C. (2003). Ruimte om te sterven. Een weg voor zieken, naasten en zorgverleners [Space to die: A way for patients, relatives, and carers]. Tielt, Belgium: Uitgeverij Lannoo nv.

Leget, C. (2007). Retrieving the ars moriendi tradition. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 10, 313–319. doi:10.1007/s11019-006-9045-z

Leget, C. (2008). Van levenskunst tot stervenskunst. Over spiritualiteit in de palliatieve zorg [From art of living to art of dying. About spirituality in palliative care]. Tielt, Belgium: Uitgeverij Lannoo nv.

Lovanio, K., & Wallace, M. (2007). Promoting spiritual knowledge and attitudes: A student nurse education project. Holistic Nursing Practice, 21, 42–47. doi:10.1097/00004650-200701000-00008

Lucchetti, G., Bassi, R.M., & Lucchetti, A.L. (2013). Taking spiritual history in clinical practice: A systematic review of instruments. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing, 9, 159–170. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2013.02.004

McCord, G., Gilchrist, V.J., Grossman, S.D., King, B.D., McCormick, K.E., Oprandi, A.M., . . . Srivastava, M. (2004). Discussing spirituality with patients: A rational and ethical approach. Annals of Family Medicine, 2, 356–361. doi:10.1370/afm.71

Molzahn, A.E., & Sheilds, L. (2008). Why is it so hard to talk about spirituality? Canadian Nurse, 104, 25–29.

Monod, S., Brennan, M., Rochat, E., Martin, E., Rochat, S., & Büla, C.J. (2011). Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 1345–1357. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1769-7

Nicol, J. (2012). The use of a workshop to encourage trainers to consider spiritual care. Education for Primary Care, 23, 131–133.

O’Shea, E.R., Wallace, M., Griffin, M.Q., & Fitzpatrick, J.J. (2011). The effect of an educational session on pediatric nurses’ perspectives toward providing spiritual care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 26, 34–43. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2009.07.009

Phelps, A.C., Lauderdale, K.E., Alcorn, S., Dillinger, J., Balboni, M.T., Van, W.M., . . . Balboni, T.A. (2012). Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: Perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 2538–2544. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3766

Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., . . . Sulmasy, D. (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12, 885–904. doi:10.1089/jpm.2009.0142

Puchalski, C., & Romer, A.L. (2000). Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 3, 129–137. doi:10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129

Ronaldson, S., Hayes, L., Aggar, C., Green, J., & Carey, M. (2012). Spirituality and spiritual caring: Nurses’ perspectives and practice in palliative and acute care environments. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2126–2135. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04180.x

Vermandere, M., Bertheloot, K., Buyse, H., Deraeve, P., De Roover, S., Strubbe, L., . . . Aertgeerts, B. (2013). Implementation of the ars moriendi model in palliative home care: A pilot study. Progress in Palliative Care, 21, 278–285. doi:10.1179/1743291X12Y.0000000048

Vermandere, M., De Lepeleire, J., Smeets, L., Hannes, K., Van Mechelen, W., Warmenhoven, F., . . . Aertgeerts, B. (2011). Spirituality in general practice: A qualitative evidence synthesis. British Journal of General Practice, 61, e749–e760. doi:10.3399/bjgp11X606663

Vermandere, M., Warmenhoven, F., Van Severen, E., De Lepeleire, J., & Aertgeerts, B. (in press). Spiritual history-taking in palliative home care: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Palliative Medicine.

About the Author(s)

Mieke Vermandere, MD, PhD, is a research fellow, Franca Warmenhoven, MD, PhD, is a researcher, Evie Van Severen, MS, is a researcher, Jan De Lepeleire, MD, PhD, is a professor, and Bert Aertgeerts, MD, PhD, is a full professor, all in the Department of General Practice at KU Leuven in Belgium. This study was supported, in part, by the Vlaamse Liga tegen Kanker and the Constant Van de Wiel Fund for General Practice. Vermandere can be reached at mieke.vermandere@med.kuleuven.be, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted February 2014. Accepted for publication February 2, 2015.)