Physical Activity Promotion, Beliefs, and Barriers Among Australasian Oncology Nurses

Purpose/Objectives: To describe the physical activity (PA) promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers of Australasian oncology nurses and gain preliminary insight into how PA promotion practices may be affected by the demographics of the nurses.

Design: Cross-sectional survey.

Setting: Australia and New Zealand.

Sample: 119 registered oncology nurses.

Methods: Self-reported online survey completed once per participant.

Main Research Variables: Questions assessed the PA promotion beliefs (e.g., primary healthcare professionals responsible for PA promotion, treatment stage), PA benefits (e.g., primary benefits, evidence base), and PA promotion barriers of oncology nurses.

Findings: Oncology nurses believed they were the major providers of PA advice to their patients. They promoted PA prior to, during, and post-treatment. The three most commonly cited benefits of PA for their patients were improved quality of life, mental health, and activities of daily living. Lack of time, lack of adequate support structures, and risk to patient were the most common barriers to PA promotion. Relatively few significant differences in the oncology nurses’ PA promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers were observed based on hospital location or years of experience.

Conclusions: Despite numerous barriers, Australasian oncology nurses wish to promote PA to their patients with cancer across multiple treatment stages because they believe PA is beneficial for their patients.

Implications for Nursing: Hospitals may need to better support oncology nurses in promoting PA to their patients and provide better referral pathways to exercise physiologists and physiotherapists.

Jump to a section

Although survival rates continue to improve for many cancers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016), cancer treatments (e.g., surgery, hormonal therapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy) can contribute to acute, late-term, and long-term side effects. These treatments may negatively alter patients’ body composition and physical function, leading to increased risk of other orthopedic and cardiovascular conditions (Bundred, 2012; Kintzel, Chase, Schultz, & O’Rourke, 2008; Oefelein, Ricchiuti, Conrad, & Resnick, 2002; Young et al., 2014). These treatment-related effects may also negatively affect many aspects of quality of life (QOL), including sleep and urinary and sexual function, adversely affecting many aspects of their lives and health status (Carter, Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Blythe, & Neville, 2011; Flynn et al., 2011; Keogh, Patel, MacLeod, & Masters, 2013; Ottenbacher et al., 2013).

Many of the adverse effects of cancer-related treatments have been shown to be reduced by regular physical activity (PA) (Keogh & MacLeod, 2012; Mishra et al., 2012). Specifically, PA has been shown to significantly improve muscular strength, muscular and aerobic endurance, physical function, and many aspects of QOL, including improved sexual health and reduced fatigue (Keogh & MacLeod, 2012; Mishra et al., 2012). Research also suggests that PA may reduce the likelihood of developing other chronic diseases and have survival benefits for a variety of groups of patients with cancer (Demark-Wahnefried, Campbell, & Hayes, 2012; Newton & Galvão, 2016). As a result of this evidence, leading cancer organizations, including the American Cancer Society, and Exercise and Sports Science Australia have published position statements outlining the importance of PA for cancer survivorship (Hayes, Spence, Galvão, & Newton, 2009; Rock et al., 2012). However, the majority of people with cancer still do not engage in sufficient PA to obtain health benefits, with their PA rates often being less than their age-matched, cancer-free peers (Stacey, James, Chapman, Courneya, & Lubans, 2015; Stevinson, Lydon, & Amir, 2014).

Considerable research has sought to understand patients’ perspectives and determinants of PA to better inform health promotion policies and increase their PA levels (Husebø, Dyrstad, Søreide, & Bru, 2013; Lee, Kim, & Merighi, 2015; Rogers et al., 2004; Thorsen, Courneya, Stevinson, & Fosså, 2008). A key finding of this research is that the support of important others (e.g., partners, family, friends, healthcare professionals) can facilitate increased PA in patients, with oncology nurses likely being one of the most influential healthcare professional groups (Karvinen, McGourty, Parent, & Walker, 2012; Keogh, Olsen, Climstein, Sargeant, & Jones, 2015). Oncology nurses and other healthcare professionals who wish to promote PA to their patients may face several challenges in that this is not their primary area of training or scope of practice and they receive relatively little continuing education opportunities about the benefits of PA for their patients. However, an interdisciplinary approach in which oncology nurses work with oncologists and other allied healthcare professionals to promote PA to their patients (and provide some general guidelines) should be considered, particularly in situations in which exercise specialists (exercise physiologists and physiotherapists) are unavailable or difficult to access.

Of all the allied healthcare professionals, nurses are ideally placed to promote PA to their patients because they may have more frequent patient contact and more time for discussing patient concerns than oncologists (Leahy et al., 2013). However, little is known regarding to what extent and how oncology nurses may promote PA to their patients or the determinants (e.g., beliefs, barriers) of their PA promotion (Karvinen et al., 2012; O’Hanlon & Kennedy, 2014; Stevinson & Fox, 2005; Williams, Beeken, Fisher, & Wardle, 2015). Of these four studies, two surveyed a range of healthcare professionals, including oncology nurses, with results showing data for the entire sample of mixed healthcare professionals (O’Hanlon & Kennedy, 2014; Williams et al., 2015). Therefore, only two studies provided explicit data on oncology nurses’ PA promotion practices (Karvinen et al., 2012; Stevinson & Fox, 2005) and only one study described the actual benefits that nurses believe PA may have for their patients (Karvinen et al., 2012). In contrast, all four studies reported numerous barriers that oncology nurses and other healthcare professionals have in promoting PA to their patients (Karvinen et al., 2012; O’Hanlon & Kennedy, 2014; Stevinson & Fox, 2005; Williams et al., 2015). Of note, all of these studies were conducted outside of Australia and New Zealand. This is particularly pertinent because clinical exercise physiology is a new profession in Australia and New Zealand, meaning that relatively few exercise physiologists currently work with patients with cancer. This would imply that Australasian oncology nurses may play an important role in the promotion of PA to patients with cancer, but such activity is undocumented in the peer-reviewed literature.

The current study aimed to address these limitations by documenting PA promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers of oncology nurses in Australia and New Zealand (Australasia). A secondary goal was to gain preliminary insight into whether these practices and determinants were influenced by the nurses’ hospital location (rural, regional, and metropolitan) or years of work experience.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed to gain some insight into the PA promotion practices and beliefs of Australasian oncology nurses. Data were obtained using an online, web-based survey (SurveyMonkey®) that has been described previously (Puhringer et al., 2015). The questions contained in the online survey were based on two key theoretical frameworks within cancer health behavior research, namely the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and social cognitive theory (SCT) (Husebø et al., 2013; Karvinen & Vallance, 2015; Rogers et al., 2004; Thorsen et al., 2008). In an attempt to minimize potential response bias, the survey included identically phrased questions regarding the promotion practices and beliefs of the oncology nurses regarding three healthy behaviors (PA, healthy eating, and smoking cessation). Data related to healthy eating outcomes have been previously published (Puhringer et al., 2015).

Participants and Procedures

Australasian oncology nurses who routinely work with patients with cancer were invited to participate in the online survey by two methods. These methods included accessing a link to the survey on the Cancer Nurses Society of Australia (CNSA) website or by responding to an email from the Cancer Nurses Section of the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO). Both of these methods, by which the relevant nursing organizations informed their members about the research project, provided the nurses with a description of the research project and articulated the process by which they could give informed consent to their participation. Other RNs providing health care to patients with cancer but who were not members of the two relevant nursing organizations were also eligible to participate and were recruited via links posted on Twitter and Facebook.

The Bond University Human Review Ethics Committee and the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee provided ethical clearance for this project, with the CNSA and NZNO also providing organizational approval to approach their members. To assist with participant recruitment, 24 $20 gift vouchers were randomly allocated to respondents who answered all of the questions in the online survey. All participants provided informed consent electronically on the main survey page to gain access to the online survey.

Instrument

The TPB- and SCT-based online questionnaire used for this study has been previously described (Puhringer et al., 2015). The TPB describes how normative beliefs, perceived control, and intentions may influence behavior (Azjen, 1985), and SCT focuses on how behavioral, personal, and environmental factors may influence behavior (Bandura, 1986). The survey questions were designed to ask questions relevant to the TPB and SCT constructs, as well as to draw on the literature on PA determinants of patients with cancer and PA promotion practices of oncology healthcare professionals (Blanchard, Courneya, Rodgers, & Murnaghan, 2002; Jones, Courneya, Fairey, & Mackey, 2005; Karvinen et al., 2012; O’Hanlon & Kennedy, 2014). Specifically, the questionnaire used the guiding principles of TPB and SCT to assess how oncology nurses promoted PA, their attitudes toward beneficial effects of PA in patients with cancer, and their perceived barriers for PA promotion. The primary components of the TPB include normative beliefs, perceived control, and intentions (Azjen, 1985); the theory is particularly pertinent because it emphasizes the perceived beliefs that individuals assume are held by other people. This is known as the subjective norm and allows consideration of social demands that may influence behavior. In relation to this particular study, examples of items in the survey that mapped this part of the TBP included statements such as, “My fellow cancer nurses believe I should be promoting physical activity to my cancer patients,” which reflects the subjective norm. Similarly, SCT emphasizes the thought processes that govern behavior and specifically asserts that behavior change or maintenance is determined by a personal sense of control. An example statement in the questionnaire aligned with this is, “Whether or not I promote physical activity to my cancer patients is entirely up to me.”

The wider survey was comprised of four main sections: the demographics of the oncology nurses and three possible areas of health promotion (i.e., PA, diet, and smoking habits) throughout the different stages of treatment for their patients with cancer. Questions about PA, as well as dietary and smoking habits, were included to minimize response bias; nurses who did not promote PA had the potential to be more likely to not participate in this project. The current study only provides a description of data relevant to the PA promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers of the oncology nurses.

The oncology nurses’ demographic characteristics and current lifestyle habits were also obtained. These included age, gender, highest level of professional qualification, years of nursing practice, practice type (public or private), hospital location (metropolitan, regional, or rural), and cancer specialization (if applicable). To describe the oncology nurses’ healthy lifestyle habits, they were asked to provide information about their current PA, dietary, and smoking behavior.

The PA promotion practices of the oncology nurses were obtained via their answers to several multiple-choice questions. Their opinions on which professional groups had the greatest responsibility for PA promotion in their hospital and their attitudes toward PA promotion during different stages of cancer treatment (pre-, during, and post-treatment) were investigated with multiple-choice items. Respondents were also asked to describe the beneficial effects PA may have for their patients using a Likert-type scale in which the possible responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) on seven potential benefits. These benefits included improvements in health-related QOL; weight management; mental health; activities of daily living; and reduced risk of cancer recurrence, other diseases, and tumor-specific comorbidities. In addition, respondents were asked their opinion on whether they believe that their patients are generally uninterested in PA, whether promoting PA is entirely up to them (i.e., responsibility of the nurse), whether they should promote PA, and whether a strong evidence base exists to promote PA.

The respondents were asked to rank, in order, their three primary barriers to PA and other healthy behavior promotion. Barrier options included a lack of time, adequate support structures, expertise, or knowledge; risk to patient; being outside of perceived scope of practice; and not having any barriers for PA promotion (Brandes, Linn, Smit, & van Weert, 2015; Keogh, Patel, MacLeod, & Masters, 2014).

Statistical Analyses

A principal component analysis with varimax rotation was performed. Each component (personal sense of control, subjective norm, and attitude) loaded onto constructs from the theoretical frameworks of the TPB and the SCT that guided survey development. Internal consistency of the three components was demonstrated by a scores of 0.94, 0.92, and 0.87, respectively.

The demographics, PA promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers of oncology nurses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Descriptive data were presented as mean and standard deviation or counts and frequencies for the continuous and categorical data, respectively. Subgroup comparisons were conducted for hospital location (regional and rural versus metropolitan) and years of nursing practice (fewer than 25 versus 25 or more) because the sizes of the subgroups were similar. Potential subgroup comparisons were not conducted on the basis of gender (female versus male), hospital type (private versus public), or cancer group specialization as a result of unbalanced sample sizes. One-way analyses of variance and chi-squared tests were used for the applicable subgroup analyses of the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. As is common for survey research, a small number of participants did not answer every question. Therefore, a pairwise statistical approach was used, with the number of respondents for each question being provided in the relevant tables. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS®, version 22.0, with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

All registered CNSA and NZNO members who supplied an email address to their respective organizations were sent an email from October 2013 to July 2014 that described the study and included a link to the online questionnaire. One hundred and nineteen Australasian RNs answered the online questions related to PA promotion, but not all participants answered all demographic questions. The exact response rate or the proportion of oncology nurses who responded to an invitation from their oncology nursing association or via social media was unknown. Because these nursing associations had about 2,000 members at the time of data collection, this resulted in a recruitment rate of about 6% of total members.

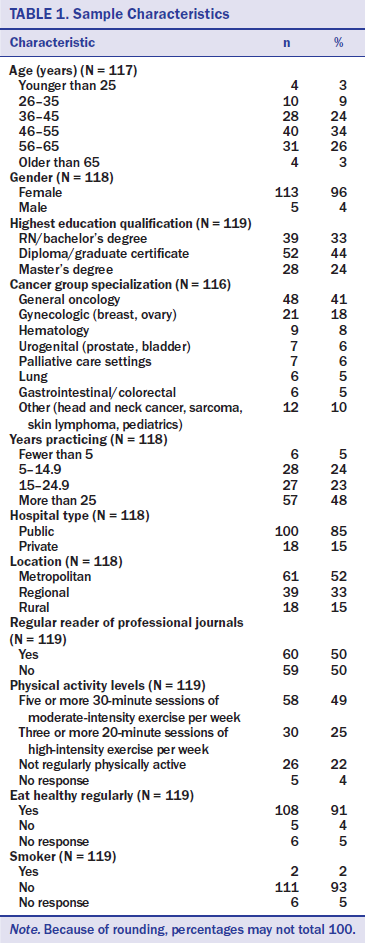

The demographic characteristics of the nurses are summarized in Table 1. Almost all participants were female, with the mean age of the sample being 48.5 years (SD = 10.6) and the mean years of nursing practice being 23 (SD = 12). General oncology was the most common area in which the nurses currently worked. Most of the oncology nurses worked in public hospitals compared to private ones. The majority of the participants (n = 88, 74%) described themselves as physically active, based on their weekly frequency of moderate or vigorous PA.

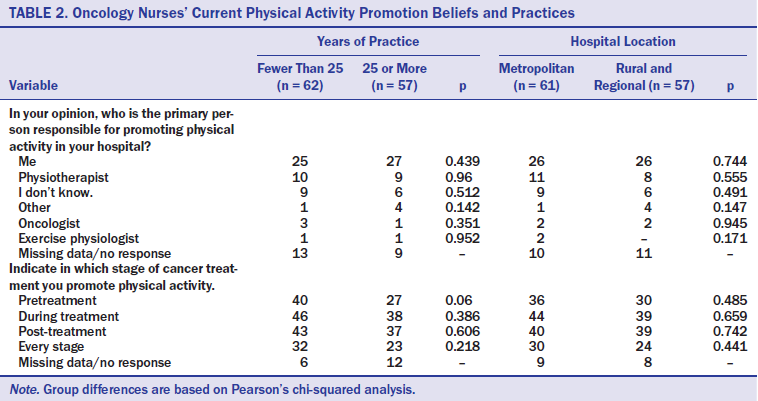

The PA promotion practices of the oncology nurses are summarized in Table 2. Oncology nurses considered themselves the primary professional group for promoting PA to their patients. Many of the respondents felt that they most commonly promoted PA during cancer treatment. Years of practice (25 or more versus fewer than 25) or hospital location (rural and regional versus metropolitan) had no significant effect on the PA promotion practices of the oncology nurses.

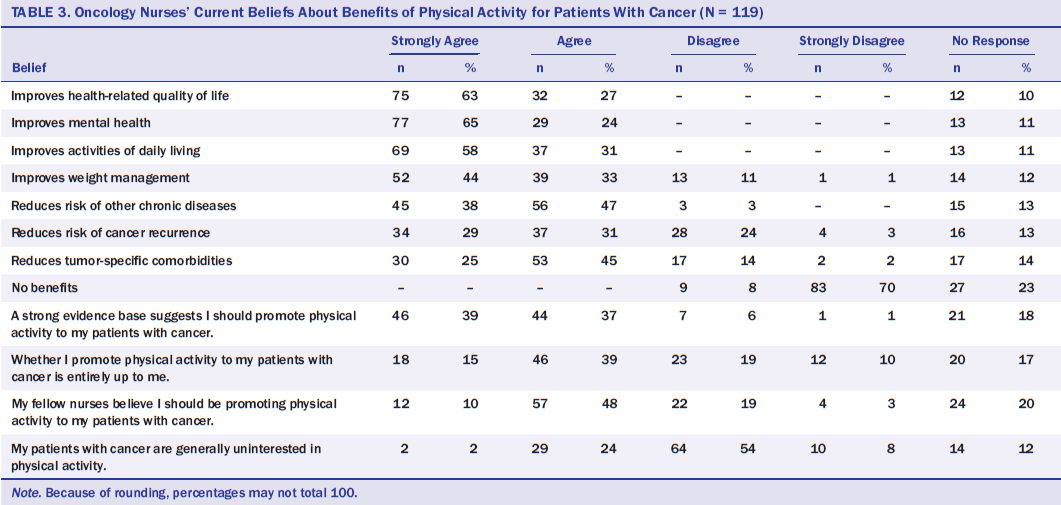

The PA promotion beliefs of the oncology nurses are summarized in Table 3. A majority of the oncology nurses believed that PA had many benefits for their patients. Specifically, they agreed or strongly agreed that PA could improve their patients’ health-related QOL (n = 107, 90%), mental health (n = 106, 89%), and activities of daily living (n = 106, 89%), while also reducing their risk of developing other chronic diseases (n = 101, 85%). The PA promotion practices of the oncology nurses was largely based on their beliefs of the benefit of PA for cancer survivorship, with 90 (76%) of the oncology nurses believing the level of evidence supporting the benefits of PA promotion to their patients was strong.

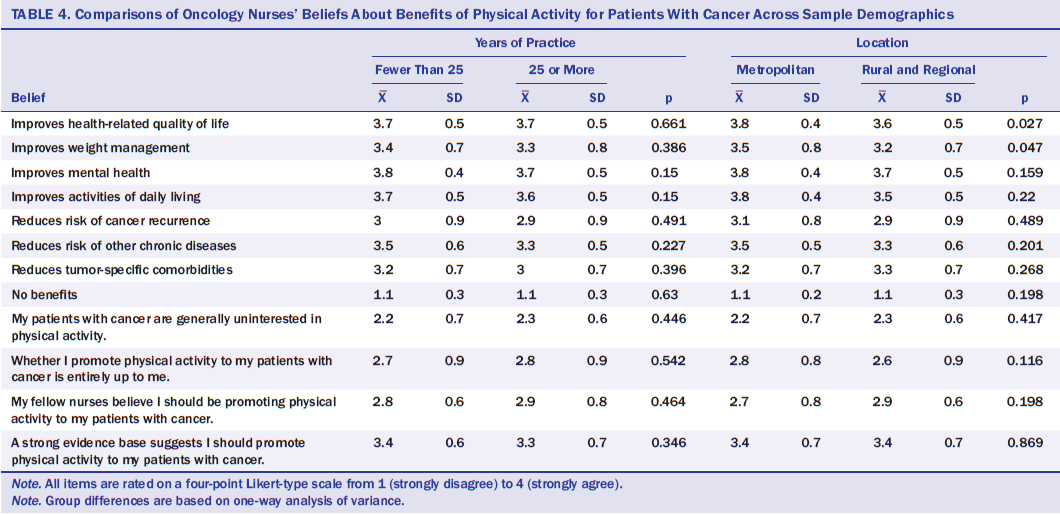

Table 4 compares oncology nurses’ current beliefs toward PA promotion across years of practice and hospital location (metropolitan versus rural and regional). No significant differences were found in PA promotion beliefs based on years of practice. In contrast, oncology nurses working in metropolitan hospitals were significantly more likely to believe that PA could improve health-related QOL, weight management, and activities of daily living than their counterparts working in rural and regional areas.

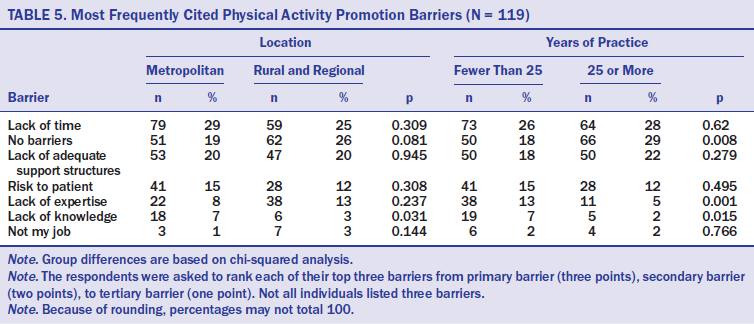

The barriers to PA promotion by the oncology nurses are summarized in Table 5. The three most commonly cited barriers were lack of time, lack of adequate support structures, and risk to patient. Of note, 116 oncology nurses reported no barriers in promoting PA to their patients. Oncology nurses working in metropolitan hospitals were significantly more likely to cite a lack of knowledge as a barrier to PA promotion than those working in rural and regional hospitals. Experienced nurses (more than 25 years of practice) were more likely to state that they had no barriers in promoting PA than those with less than 25 years of practice. The experienced nurses were less likely to cite a lack of expertise and knowledge as barriers to PA promotion than their less experienced counterparts.

Discussion

In light of the results of systematic reviews demonstrating the benefits of PA for patients with cancer (Keogh & MacLeod, 2012; Mishra et al., 2012), the current study was conducted to gain insight into PA promotion practices, beliefs, and perceived barriers of Australasian oncology nurses.

The results demonstrated that Australasian oncology nurses felt that they were the primary healthcare professional group providing general PA advice to their patients. Although this role lies outside their primary areas of training, it appears consistent with previous research, in which many oncology nurses also promoted PA (Karvinen et al., 2012; Stevinson & Fox, 2005), healthy eating (Puhringer et al., 2015), and sexual health (Kotronoulas, Papadopoulou, & Patiraki, 2009) to their patients. The important role oncology nurses felt they played in promoting PA to their patients may reflect the more frequent opportunities they have to interact with patients with cancer than oncologists or exercise specialists (exercise physiologists or physiotherapists). The perceived low involvement of these exercise specialists in promoting PA to patients with cancer may reflect the relative infancy of the exercise oncology literature and the relative lack of exercise specialists within interdisciplinary oncology care teams. Alternately, the nurses’ beliefs that oncologists play a minor role in promoting PA appears contrary to previous research, whereby 43% of oncologists try to promote PA to their patients (Jones, Courneya, Peddle, & Mackey, 2005) and 64% enquire about their patients’ PA during some to most visits (Karvinen, DuBose, Carney, & Allison, 2010). Regardless of these differences in the perceived role of different healthcare professionals, patients with cancer are most likely to benefit when oncologists, oncology nurses, and exercise specialists work as part of an interdisciplinary team (Keogh et al., 2015).

The results of the current study indicated that more than half of the oncology nurses promoted PA to their patients pre-, during, and post-treatment, with almost half promoting PA at all three treatment stages. This relatively high prevalence of PA promotion appears to be consistent with U.S. data, whereby 75% of oncology nurses enquired about their patients’ PA levels on every visit or most visits (Karvinen et al., 2012) and U.K. data, whereby 65% of oncology nurses were in favor of PA programs for patients with cancer (Stevinson & Fox, 2005). The promotion of PA across treatment phases is vital because each stage of treatment may pose somewhat different body composition, muscular function, QOL, and overall health status risks that may be attenuated with PA (Bundred, 2012; Kintzel et al., 2008; Oefelein et al., 2002; Young et al., 2014).

The relatively high rate of PA promotion reported by oncology nurses in the current study appears to be consistent with their own PA promotion beliefs, whereby 76% agreed or strongly agreed that a strong evidence base exists for PA promotion to patients with cancer. The strongest benefits the oncology nurses had for PA were for improved patient QOL, mental health, and activities of daily living, and reductions in the risk of other chronic disease, with about 85% of the sample agreeing or strongly agreeing to these benefits. In contrast, oncology nurses were less convinced of the benefits of PA for reducing tumor-specific comorbidities and risk of cancer recurrence. The oncology nurses’ beliefs regarding the benefits of PA for their patients were largely evidence-based because systematic reviews have demonstrated substantial PA-related improvements in patients’ physical function, activities of daily living, and aspects of QOL and mental health (Keogh & MacLeod, 2012; Mishra et al., 2012). Such results are encouraging because previous research suggested that 58% of oncology nurses were unaware of the specific benefits of PA for patients with cancer (Stevinson & Fox, 2005). Therefore, the improved understanding of the exercise literature by oncology nurses in the current study may reflect the rapid increase of published research during the past decade and these nurses’ willingness to complete professional development activities that improve patient outcomes.

The oncology nurses believed a moderately high proportion of their patients were interested in PA (n = 74, 62%). This perception appears to be somewhat consistent with other studies, in which similar proportions of patients with cancer have reported interest in the benefits of healthy behaviors (Anderson, Steele, & Coyle, 2013; Demark-Wahnefried, Peterson, McBride, Lipkus, & Clipp, 2000; Keogh et al., 2014). Collectively, these results suggest that, if nurses and other allied healthcare staff are to be successful in assisting their patients with increasing their PA levels, they may first have to educate some of their patients regarding the benefits of PA for cancer survivorship. The oncology nurses did not hold strong views on how promoting PA was their own personal decision (64 [54%] agreed or strongly agreed) or whether other oncology nurses would expect them to do this on a regular basis (69 [58%] agreed or strongly agreed). The relative equivalence of the nurses’ views regarding whether to promote PA was their own decision and if their peers expect them to do this on a regular basis appears understandable because PA promotion is not one of their core activities.

The current study also sought to identify some of the primary barriers that oncology nurses may have in promoting PA to their patients. Almost a fourth of the respondents cited having no barriers to PA promotion. The result is encouraging because these nurses may be able to play key leadership roles in assisting other oncology nurses in feeling more comfortable promoting PA to their patients. Alternatively, more than 75% of the respondents cited barriers to their PA promotion, with the primary barriers being lack of time, lack of adequate support structures, risk to patient, and lack of their own PA expertise. Such results appear to be consistent with international studies that demonstrated that oncology nurses (Karvinen et al., 2012; Stevinson & Fox, 2005) and oncologists (Jones, Courneya, Peddle, & Mackey, 2005; Karvinen et al., 2010) also cited a lack of time and support structures as some of the key barriers to promoting PA to their patients. These results suggest that cancer institutions should investigate strategies to assist their staff in overcoming these barriers. Inclusion of some continuing education or professional development on how to use evidence-based behavior change models to promote PA or refer patients to exercise specialists may be useful, as could the provision of greater interdisciplinary working relationships with exercise specialists. However, overcoming the primary barrier of lack of time is challenging because of the already busy schedule of oncology nurses and the wide roles they already play in many hospitals. Developing referral pathways in which oncology nurses can more easily refer patients to exercise specialists may overcome this barrier.

The current study sought to gain preliminary insight into whether the PA promotion practices, beliefs, or barriers of the oncology nurses were influenced by their years of experience or hospital location. Relatively few significant differences in these perceptions were observed between the various subgroups of oncology nurses. However, compared to regional and rural nurses, those working in metropolitan hospitals had stronger views on the benefits of PA for their patients’ QOL, weight management, and ability to perform activities of daily living. However, a significantly greater percentage of metropolitan nurses cited a lack of knowledge as a barrier to PA promotion than their regional and rural peers. Such apparently contradictory findings may indicate that the greater knowledge of the benefits of PA reported by metropolitan nurses does not necessarily translate into them having the knowledge base to confidently provide patients with general or specific advice on the types of PA they should perform for health benefit.

Similarly, some minor differences were found in the primary barriers between oncology nurses with varying degrees of experience. Oncology nurses with more than 25 years of experience were significantly more likely to report no barriers to promoting PA to their patients and significantly less likely to cite a lack of expertise and knowledge as barriers to PA promotion. These findings appear to be consistent with the wider knowledge base of more experienced nurses (Miles, Simon, & Wardle, 2010) and the greater probability of metropolitan patients with cancer being able to access exercise physiologists and physiotherapists than patients in regional and rural hospitals. However, the relative lack of effect of years of practice and hospital location on the PA promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers of the oncology nurses is positive in that it may suggest that these results are relatively generalizable across other Australasian oncology nursing settings.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. Only 119 nurses completed the questions pertaining to PA in the online survey. Such a sample size represents a fraction (less than 6%) of Australasian oncology RNs. The overall representation of this sample is also affected by the finding that, in general, these nurses were based in public hospitals and were more experienced and engaged in more healthy behaviors (e.g., PA levels, dietary and smoking habits) than would be anticipated from most Australasian oncology nurses. As such, the current sample may not be fully representative of the population. However, the current study’s sample size is larger than (O’Hanlon & Kennedy, 2014; Spellman, Craike, & Livingston, 2014) or comparable to other studies using quantitative surveys to provide insight into how healthcare professionals may promote PA to their patients with cancer (Daley, Bowden, Rea, Billingham, & Carmicheal, 2008; Karvinen et al., 2010). Whether the respondents in the current study worked in hospitals that employed exercise physiologists or physiotherapists and whether this would have any effect on their PA promotion practices, beliefs, and barriers also remains unclear. In addition, when developing the survey for the current study, the authors felt that requesting details on whether a specific exercise prescription (e.g., mode, intensity, duration, frequency) was commonly discussed with patients would have resulted in an overly long survey that would reduce response rates. This is an additional limitation because evidence suggests that more vigorous PA (including resistance training) may have greater benefits than moderate-intensity PA, such as walking, for patients with cancer (Keogh & MacLeod, 2012; Lee et al., 2015).

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"30126","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"281","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"365"}}]]

Conclusion

The results of the current study add to the scant literature on how healthcare professionals may promote PA to their patients with cancer, particularly those employed in Australasia, where few patients have access to clinical exercise physiologists. Specifically, research is limited on how Australasian healthcare professionals promote healthy behavior to their patients with cancer (Spellman et al., 2014). International research examining the PA promotion practices of oncology nurses is also limited (Karvinen et al., 2012; Stevinson & Fox, 2005). The aim of the current study was to stimulate additional research that recruits larger samples to gain better insight into how the demographics of oncology nurses may affect their PA promotion practices and determinants to their patients, as well as how oncology nurses and other members of the oncology interdisciplinary team may best work together to increase their patients’ PA levels. As a part of an interdisciplinary team, oncology nurses appear to be ideally placed to provide general evidence-based information about the benefits of PA, which can be obtained from organizations including the Oncology Nursing Society, American College of Sports Medicine, and Exercise and Sports Science Australia, and discuss the primary facilitators and barriers that may affect their patients’ PA levels. The authors recommend that oncology nurses endeavor to refer patients who require more specific exercise prescription advice or who have multiple comorbidities or potential exercise contraindications to exercise physiologists or physiotherapists.

About the Author(s)

Keogh is an associate professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine at Bond University in Queensland, Australia, and an adjunct associate professor in the Human Potential Centre at Aukland University of Technology in New Zealand and the Cluster for Health Improvement in the Faculty of Science, Health, Education, and Engineering at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland; Pühringer is a medical doctor in the Department of Neurology at the General Hospital of the Merciful Brothers in Granz, Austria; Olsen is a PhD candidate and Sargeant is an assistant professor, both in the Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine at Bond University; Jones is a senior lecturer in the School of Physical Education, Sport, and Exercise Sciences at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand; and Climstein is an adjunct associate professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Sydney and Vale Medical Clinic in Australia. No financial relationships to disclose. Keogh, Olsen, Sargeant, Jones, and Climstein contributed to the conceptualization and design. Olsen, Sargeant, and Climstein completed the data collection. Keogh, Pühringer, and Climstein provided statistical support. Keogh, Pühringer, Sargeant, and Climstein provided the analysis. All of the authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Keogh can be reached at jkeogh@bond.edu.au, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted April 2016. Accepted for publication June 6, 2016.