Experiences of Family Members of Dying Patients Receiving Palliative Sedation

Purpose/Objectives: To describe the experience of family members of patients receiving palliative sedation at the initiation of treatment and after the patient has died and to compare these experiences over time.

Design: Descriptive comparative study.

Setting: Oncology ward at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel.

Sample: A convenience sample of 34 family members of dying patients receiving palliative sedation.

Methods: A modified version of a questionnaire describing experiences of family members with palliative sedation was administered during palliative sedation and one to four months after the patient died. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the results of the questionnaire, and appropriate statistical analyses were conducted for comparisons over time.

Main Research Variables: Experiences of family members and time.

Findings: Most relatives were satisfied with the sedation and staff support. Palliative sedation was experienced as an ethical way to relieve suffering. However, one-third felt that it shortened the patient’s life. An explanation of the treatment was given less than half of the time and was usually given on the same day treatment was started. This explanation was given by physicians and nurses. Many felt that they were not ready for changes in the patient’s condition and wanted increased opportunities to discuss the treatment with oncology care providers. No statistically significant differences in experiences were found over time.

Conclusions: Relatives’ experiences of palliative sedation were generally positive and stable over time. Important experiences included timing of the initiation of sedation, timing and quality of explanations, and communication.

Implications for Nursing: Nurses should attempt to initiate discussions of the possible role of sedation in the event of refractory symptoms and follow through with continued discussions. The management of refractory symptoms at the end of life, the role of sedation, and communication skills associated with decision making related to palliative sedation should be a part of the core nursing curriculum. Nursing administrators in areas that use palliative sedation should enforce good nursing clinical practice as recommended by international practice guidelines, such as those of the European Association for Palliative Care.

Jump to a section

Relieving suffering is one of the main aims of oncology care, particularly for dying patients (Bruce, Hendrix, & Gentry, 2006; World Health Organization, 2016). The suffering of a dying patient sometimes includes refractory symptoms. These symptoms are defined as severe symptoms—physical and psychological—that cannot be treated for long periods, or their treatment will lead to uncontrollable side effects (Schildmann & Schildmann, 2014). In most cases, treatment is focused on refractory physical symptoms, such as pain, dyspnea, and delirium (Schildmann & Schildmann, 2014), but psychological and existential suffering may also produce a refractory state (Bruce & Boston, 2011; Swart et al., 2014). The frequency of palliative sedation therapy for dying patients varies from 5%–52%, according to different sources (Bruinsma, Rietjens, Seymour, Anquinet & van der Heide, 2012; de Graeff & Dean, 2007), reflecting the wide range of the definition of palliative sedation, cultures, and practices (Maltoni, Scarpi & Nanni, 2014; Rosengarten, Lamed, Zisling, Feigin, & Jacobs, 2009; van Deijck, Hasselaar, Verhagen, Vissers, & Koopmans, 2013). Many of the patients who receive palliative sedation are patients with cancer (van Deijck et al., 2013).

Palliative care is meant to improve the quality of life and relieve suffering of all patients, including dying patients, and their families (Cherny & Radbruch, 2009; van Dooren et al., 2009). The recommended treatment for a dying patient suffering from refractory symptoms is palliative sedation (Cherny & Radbruch, 2009; Mercadante et al., 2009). Various definitions of palliative sedation appearing in the literature are based on two main factors: (a) intolerable suffering that cannot be treated by routine methods and (b) use of medications to relieve suffering without the intention to cause death (American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2014; Cellarius, 2014; Morita, Tsuneto, & Shima, 2002).

Nurses play an important role in palliative sedation. Control of symptoms is an important part of the oncology nurse’s role (Patel, Gorawara-Bhat, Levine, & Shega, 2012). As advocates, nurses are often involved with the interdisciplinary team decision to use sedation and support patients and their families during the decision-making process. Nurses also play a more active role because they are the healthcare providers who usually start the sedation infusion and assess the condition of the patient once sedated (Arevalo, Rietjens, Swart, Perez, & van der Heide, 2013; Bruce & Boston, 2011; Gielen, van den Branden, van Iersel, & Broeckaert, 2012). However, this involvement can lead to feelings of ethical conflict and burden (Abarshi, Papavasiliou, Preston, Brown, & Payne, 2014; Gielen et al., 2012) and may place nurses in a precarious position in terms of the law and bioethics (Parker, Paine, & Parker, 2011).

According to the principles of family-centered care, treatment for dying patients and their family members should take into consideration their physical and psychosocial state (Cherny & Radbruch, 2009; Mercadante et al., 2009) and provide emotional and physical support, medical advice, and education (Bruinsma et al., 2012; Cherny & Radbruch, 2009; Lawson, 2011). Family members of the dying patient are defined as blood relatives, spouses, children, distant relatives, or friends who care for the patient (Panke & Ferrell, 2011). They remain with the patient in his or her last days, are involved in and influenced by treatment (Namba et al., 2007), and should understand the aim of care (Cherny & Radbruch, 2009; Namba et al., 2007).

In a systematic review of studies of relatives’ experiences with palliative sedation, Bruinsma et al. (2012) reported that members of the dying patient’s family are often distressed and feel anger, frustration, disappointment, concerns, struggles, guilt, helplessness, and exhaustion. These experiences can be the trigger to start palliative sedation to improve the patient’s quality of life and relieve the stress on family members who are watching the suffering of their loved one (Rietjens, Hauser, van der Heide, & Emanuel, 2007).

Although the main goal of palliative sedation is to relieve suffering, family members have been found to have mixed feelings about its use. On one hand, family members had positive feelings toward palliative sedation because they felt that it decreased the patient’s distress and suffering and led to a peaceful death (Bruinsma et al., 2012; Bruinsma, Rietjens, & van der Heide, 2013). On the other hand, relatives had negative feelings about palliative sedation. They were concerned that palliative sedation is a form of euthanasia or physician-assisted dying that may hasten the patient’s death (Parker et al., 2011; Rich, 2012; van Dooren et al., 2009). Others expressed concerns about continued suffering during the therapy (Bruinsma et al., 2012; van Dooren et al. 2009). In addition, family members were distressed and anxious because of feelings of guilt and the burden of responsibility for making the decision to begin sedation (Morita et al., 2004; Rietjens et al., 2007), for being unprepared for changes in the patient’s condition (Morita et al., 2004), and for overall exhaustion and fatigue during their relative’s dying process (Bruinsma et al., 2012; van Dooren et al., 2009). Whether these feelings decrease with time, similar to normal feelings of grief and mourning, is unknown.

Few studies have investigated the experiences of family members of patients in the terminal phase of illness receiving palliative sedation, and no studies were found that investigated these experiences over time. The purpose of the current study is to describe the experience of family members of patients receiving palliative sedation at the initiation of treatment and after the patient has died and to compare these experiences over time.

Methods

A convenience sample of 34 family members of dying patients receiving palliative sedation therapy on an oncology ward in Israel were included in this study. The criteria for inclusion were (a) being an immediate family member (mother, father, brother, sister, spouse, son, or daughter) of a patient receiving palliative sedation or a friend staying with the patient in his or her last days who was emotionally involved with the patient, (b) having the ability to read Hebrew or Russian, and (c) being aged older than 18 years. The exclusion criterion was having a history of mental illness.

Several respondents felt the need to share additional feelings with the investigators, and their unsolicited comments were written on their questionnaires. These responses were reviewed and then categorized into themes.

Data Collection

After receiving approval from the institutional ethics review board at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel, all family members who met the inclusion criteria were individually approached by one of the investigators while their family member was receiving palliative sedation. Those who agreed to participate then were asked to sign an informed consent form, complete the study questionnaire, and complete the same questionnaire again by telephone one to four months after the death of their loved one. Thirty-eight families were asked to participate in the study, and 34 agreed. Of the 34 who agreed to fill out the first questionnaire, 8 refused to answer at the second data collection period after the death of the patient.

Instruments

The questionnaire used in this study was based on a questionnaire developed by Morita et al. (2004). The purpose of the original questionnaire was to describe the experiences of family members of patients receiving palliative sedation in Japan. The original questionnaire was modified so that scales of the various subsections of the tool would be consistent and more sensitive (i.e., more response options). Additional questions were also added to increase the description of the experience. The modified questionnaire consisted of four sections. The first section included demographic and background data of the family member or study participant (age, gender, relationship to the patient, education level, profession, birthplace, immigration date, family status, religion, religiosity [a measure of ethnicity in Israel], and health status). The second section included demographic and background data related to the patient receiving the palliative sedation (age, gender, length of illness, length of hospital stay, type of cancer, and symptoms). The third section contained 16 questions related to the participant’s experience concerning the palliative sedation. Questions were related to satisfaction with patient care and palliative sedation, initiation of sedation, and communication with healthcare professionals before and during sedation. This section was scored on a five-point Likert-type scale. The fourth section described experiences related to regret and ethical issues associated with the use of palliative sedation. This section was scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Although the original questionnaire was composed in Japanese, an English version was sent to the authors of the current study by its originators. The questionnaire was then forward- and reverse-translated from English into Hebrew and Russian and then back-translated according to Brislin’s method (Regmi, Naidoo, & Pilkington, 2010). Content validity of the questionnaire was checked by two experts in palliative care. Small changes were made to increase the questionnaire’s sensitivity. Reliability was checked using Cronbach alpha, with results being 0.87 for time 1 (T1) and 0.84 for time 2 (T2). The test-retest reliability for the fourth part of the questionnaire from T1 to T2 was found to be 0.7.

Data Analysis

Data were transcribed into a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet and then transferred to SPSS®, version 20.0, for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample and results of the questionnaire. Differences from T1 to T2 were determined using McNemar’s test for a dichotomous variable, the Test of Marginal Homogeneity for a nominal variable, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for an ordinal variable, and the paired-samples t test for continuous variables.

Some of the participants in the study felt the need to share additional feelings with the investigators. These open-ended responses were added to the closed-ended questionnaire. These responses were collected and coded into themes by two of the investigators.

Results

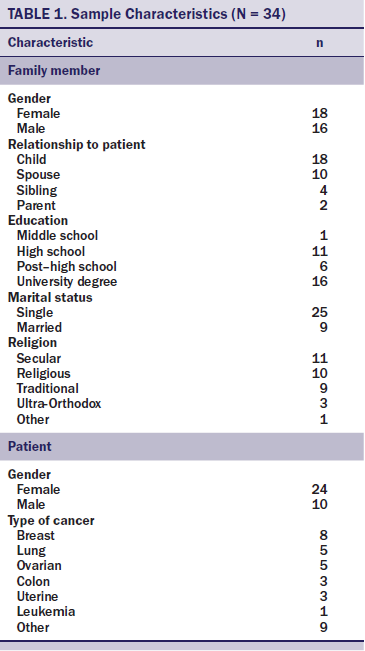

Demographic characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 1. The mean age of family member participants was 50.9 years (range = 19–77, SD = 15.4), with similar numbers of males and females. Most participants were children and spouses of the patient. The mean patient age was 62.3 years (range = 21–89, SD = 15.54). All patients had cancer. Most patients had symptoms of agitation, pain, and dyspnea before initiation of sedation.

Satisfaction With Palliative Sedation

Almost all of the relatives (T1: n = 32, T2: n = 24) believed that their loved ones were in distress or great distress before starting palliative sedation, and the vast majority were either satisfied or very satisfied with their care and the use of sedation medication. More than 80% (T1: n = 28, T2: n = 22) stated that the intervention resulted in adequate relief of the patient’s suffering.

Treatment Initiation

Experiences of the initiation of palliative sedation were measured by communication around the decision to start palliative sedation and the timing of the treatment. More than half of the participants (n = 19) did not discuss palliative sedation with their loved one, and, in more than two-thirds of the cases (T1: n = 23, T2: n = 17), the family member perceived that the patient did not receive an explanation of the treatment. Almost three-fourths of the family members (T1: n = 24, T2: n = 16) were not informed of this treatment option before the patients’ status deteriorated, and they received an explanation of palliative sedation only on the same day that the decision to initiate treatment was made (T1: n = 25, T2: n = 19).

At T1, the majority reported that the beginning of sedation was properly timed (n = 26), but only 62% agreed with the timing at T2 (n = 16). This change was partially explained by an increase in the number of family members from T1 to T2, who felt that the initiation of sedation was started too late (T1: n = 4, T2: n = 7).

In addition, many (T1: n = 14, T2: n = 8) felt that they were not ready for the changes in the patient’s condition. Almost no disagreements were reported about initiating palliative sedation between the patient’s relatives (T1: n= 24, T2: n = 21), between the patient and his or her family (T1: n = 33, T2: n = 21), or between the staff and family (T1: n = 28, T2: n = 21).

Ethical Implications

The ethical implications of the decision to use sedation were also explored. Almost all of the participants (T1: n = 34, T2: n = 23) felt that palliative sedation was an ethical way to decrease suffering, and the vast majority (T1: n = 30, T2: n = 24) felt that the patient not suffering any longer was very important. Many respondents (T1: n = 12, T2: n = 11) agreed that no other method could adequately relieve the suffering without sedating the patient.

Regarding the impact of sedation on the patient’s survival, almost one-third (T1: n = 11, T2: n = 7) thought that the treatment shortened the patient’s life, and a smaller proportion feared that it killed the patient. Most (T1: n = 26, T2: n = 23) did not agree that the doctors wanted to hasten the process of dying. More than 90% (T1: n = 23, T2: n = 24) did not think that the sedation disrespects the patient’s dignity and did not have concerns about legal and ethical issues regarding the treatment.

Additional Findings

No statistically significant differences from T1 to T2 were found. No statistically significant differences in responses were found based on demographic data of the respondent or the patient or clinical data related to the patient.

At T2, eight relatives expressed their desire to share experiences in addition to what was requested by the investigators. Many reflected on not receiving enough information related to sedation. For example, different family members wrote [translated from Hebrew] the following:

I felt unsupported and uninformed.

It’s a shame that no one explained enough to the patient. We didn’t know that the end was near.

I would have preferred that the caregivers would have given more information about palliative sedation, what is allowed or not for the patient.

Discussion

The primary purpose of palliative sedation is to relieve the intractable suffering of the dying patient (Schildmann & Schildmann, 2014). This purpose was achieved, according to the participants of this study. Similar to other investigations, family members were involved in making the decision to initiate palliative sedation (Shirado et al., 2013) but were often burdened by the consequences of their choice (Bruinsma et al., 2013; Hebert, Schulz, Copeland, & Arnold, 2008; van Dooren et al., 2009).

Like many other studies involving palliative care, communication played a major role in the experiences related to palliative sedation. Similar to other studies, although the frequency of physician and nurse exchanges did not change after the decision was made (Morita et al., 2004), the content of the communication was often not as effective as it could have been (Bruinsma et al., 2013; Hebert et al., 2008; Morita et al., 2004). Others have found that study participants report a lack of an explanation of palliative sedation (particularly to the patient) or an unclear explanation (Bruinsma et al., 2012, 2013; Shirado et al., 2013; van Dooren et al., 2009). This takes place even though physicians and nurses provide such explanations (Bruinsma et al., 2013; Morita et al., 2004; van Dooren et al., 2009). A qualitative study found that support for family members during end-of-life care and validation of family members’ decision making played an important part in communication with family members and led to increased feelings of comfort and trust in the healthcare staff (Cronin, Arnstein, & Flanagan, 2015).

In the current study, family members reported their perception that patients often did not receive adequate explanations, particularly regarding the consequences of sedation, and many family members would have wanted more opportunities to discuss the decision. Additional evidence of a perceived lack of communication was the common experience in the current study that the family member was not prepared for the sudden change in the physical status of the patient or the patient’s decreased ability to communicate with the family member. This may be explained by the large percentage of participants in the current study who first discussed the use of palliative sedation on the same day it was initiated and that many had not heard of the use of palliative sedation at all before that time. This lack of exposure was not found in other studies (Bruinsma et al., 2013; Morita et al., 2004; van Dooren et al., 2009). Possibly because of cultural differences between the populations studied (Baider, 2012), the lack of communication may be avoided by repeated explanations to the patient and family, particularly before the appearance of refractory symptoms (Hebert et al., 2008; Morita et al., 2005). The explanation process appears to need more time.

Perception regarding the appropriateness of the timing for the initiation of sedation changed over time. A 15% decrease was seen in the number of participants who felt that the timing of the sedation was correct, and an increase of 15% was seen in those who felt the timing to be late during the second data collection period. These results are in opposition to those of Bruinsma et al. (2013). Again, cultural differences could explain these conflicting findings, and more research is needed.

Participants in the current study had ambivalent experiences. Most (T1: n = 18, T2: n = 18) agreed that no alternative way could alleviate the distress, but more than one-third (T1: n = 12, T2: n = 11) felt that they should do more for the sedated patient. Although the vast majority (T1: n = 26, T2: n = 21) felt no change or increase in doctors’ or nurses’ care after the initiation of sedation and more than half (T1: n = 19, T2: n = 21) felt support from the staff, many (T1: n = 25, T2: n = 12) wished for more opportunities to discuss sedation, and many felt that the staff should have been more empathic. These results provide evidence for the need for increased communication with the dying patient and family members (Cherny & Radbruch, 2009; Shinjo et al., 2010).

One of the more cited ethical questions related to palliative sedation is whether the treatment may shorten the patient’s life (Maltoni et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2011; Rich, 2012; van Dooren et al., 2009). Almost one-third of participants (T1: n = 11, T2: n = 7) agreed with this, and only 10% (T1: n = 4, T2: n = 2) felt the patient died because of sedation. Most family members reported that they did not have legal or ethical concerns about the use of sedation. Suspicions associated with the legal aspects of the therapy remained stable over time. Therefore, the majority of participants in the current study did not seem to be conflicted on an ethical level about their decision to administer palliative sedation.

Limitations

Several limitations are associated with the current study. Perhaps the most significant is the study setting. The current study was conducted in only one hospital and only on one oncology ward. This fact limited the number of participants and, therefore, the statistical power. Data were collected during a two-year period, and data collection was aborted because of a fear of changes in the ward behavior and environment during such a long period. The time range from T1 to T2 varied from one to four months. Of note, no significant differences were seen from T1 to T2. In addition, the subject matter of the current study is sensitive, and those who agreed to participate may not represent the population at large. One of the investigators worked in the ward where the data were collected, which may have influenced the participants’ answers.

Recommendations and Implications for Nursing

Additional research, such as qualitative interviews, should be conducted that describe the experiences of family members in more detail. More research is needed to evaluate the experiences of patients’ families in other hospitals, particularly in hospices. In addition, interventional studies should be conducted that are aimed at improving nursing communication with family members and patients, as well as the timing of discussions related to palliative sedation. Nurses should attempt to initiate discussions of the possible role of sedation in the event of refractory symptoms. The management of refractory symptoms at the end of life, the role of sedation, and communication skills associated with decision making related to palliative sedation should be a part of the core nursing curriculum. Nursing administrators in areas that use palliative sedation should enforce good nursing clinical practice as recommended by international practice guidelines, such as those of the European Association for Palliative Care (Cherny & Radbruch, 2009).

Conclusion

Most of the family members were satisfied with the use of palliative sedation, relief of suffering, and support given by staff during the initiation of treatment and one to four months later. The results highlight the importance of communication between nurses and family members and the importance of providing timely and repeated explanations of palliative sedation. In addition, treatment should be started early enough to avoid unnecessary suffering of the patient and his or her family. Despite some fear of shortening the patient’s life by use of sedation, participants agreed that this is an ethical way to ease the suffering of the dying patient. More research, including qualitative and interventional studies, is needed to investigate this subject.

References

Abarshi, E.A., Papavasiliou, E.S., Preston, N., Brown, J., & Payne, S. (2014). The complexity of nurses’ attitudes and practice of sedation at the end of life: A systematic literature review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 47, 915–925. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.011

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. (2014). Statement on palliative sedation. Retrieved from http://aahpm.org/positions/palliative-sedation

Arevalo, J.J., Rietjens, J.A., Swart, S.J., Perez, R.S.G.M., & van der Heide, A. (2013). Day-to-day care in palliative sedation: Survey of nurses’ experiences with decision-making and performance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 613–621. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.10.004

Baider, L. (2012). Cultural diversity: Family path through terminal illness. Annals of Oncology, 23(Suppl.), 62–65. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds090

Bruce, A., & Boston, P. (2011). Relieving existential suffering through palliative sedation: Discussion of an uneasy practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 2732–2740. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05711.x

Bruce, S., Hendrix, C.C., & Gentry, J.H. (2006). Palliative sedation in end-of-life care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 8, 320–327. doi:10.1097/00129191-200611000-00004

Bruinsma, S., Rietjens, J., & van der Heide, A. (2013). Palliative sedation: A focus group study on the experiences of relatives. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16, 349–355. doi:10.1089/jpm.2012.0410

Bruinsma, S.M., Rietjens, J.A., Seymour, J.E., Anquinet, L., & van der Heide, A. (2012). The experiences of relatives with the practice of palliative sedation: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 44, 431–445. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.006

Cellarius, V. (2014). A pragmatic approach to palliative sedation. Journal of Palliative Care, 30, 173–178.

Cherny, N.I., & Radbruch, L. (2009). European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 23, 581–593. doi:10.1177/0269216309107024

Cronin, J., Arnstein, P., & Flanagan, J. (2015). Family members’ perceptions of most helpful interventions during end-of-life care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 17, 223–228. doi:10.1097/NJH.0000000000000151

de Graeff, A., & Dean, M. (2007). Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: A literature review and recommendations for standards. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 10, 67–85. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.0139

Gielen, J., van den Branden, S., van Iersel, T., & Broeckaert, B. (2012). Flemish palliative-care nurses’ attitudes to palliative sedation: A quantitative study. Nursing Ethics, 19, 692–704.

Hebert, R.S., Schulz, R., Copeland, V., & Arnold, R.M. (2008). What questions do family caregivers want to discuss with health care providers in order to prepare for the death of a loved one? An ethnographic study of caregivers of patients at end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11, 476–483. doi:10.1089/jpm.2007.0165

Lawson, M. (2011). Palliative sedation. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15, 589–590. doi:10.1188/11.CJON.589-590

Maltoni, M., Scarpi, E., & Nanni, O. (2014). Palliative sedation for intolerable suffering. Current Opinion in Oncology, 26, 389–394. doi:10.1097/cco.0000000000000097

Maltoni, M., Scarpi, E., Rosati, M., Derni, S., Fabbri, L., Martini, F., . . . Nanni, O. (2012). Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 1378–1383. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.37.3795

Mercadante, S., Intravaia, G., Villari, P., Ferrera, P., David, F., & Casuccio, A. (2009). Controlled sedation for refractory symptoms in dying patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 37, 771–779. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.020

Morita, T., Chinone, Y., Ikenaga, M., Miyoshi, M., Nakaho, T., Nishitateno, K., . . . Uchitomi, Y. (2005). Ethical validity of palliative sedation therapy: A multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted on specialized palliative care units in Japan. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 30, 308–319. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.03.016

Morita, T., Ikenaga, M., Adachi, I., Narabavashi, I., Kizawa, Y., Honke, Y., . . . Uchitomi, Y. (2004). Family experience with palliative sedation therapy for terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 28, 557–565. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.004

Morita, T., Tsuneto, S., & Shima, Y. (2002). Definition of sedation for symptom relief: A systematic literature review and proposal of operational criteria. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 24, 447–453. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00499-2

Namba, M., Morita, T., Imura, C., Kiyohara, E., Ishikawa, S., & Hirai, K. (2007). Terminal delirium: Families’ experience. Palliative Medicine, 21, 587–594. doi:10.1177/0269216307081129

Panke, J., & Ferrell, B. (2011). The family perspective. In G. Hanks, N. Cherny, N. Christakis, M. Fallon, S. Kaasa, & R. Portenoy (Eds.), Psychiatric, psychosocial, and spiritual issues in palliative medicine (pp. 1437–1444). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Parker, F.R., Paine, C.J., & Parker, T.K. (2011). Establishing an analytical framework in law and bioethics for nurses engaged in the provision of palliative sedation. Journal of Nursing Law, 14, 58–67. doi:10.1891/1073-7472.14.2.58

Patel, B., Gorawara-Bhat, R., Levine, S., & Shega, J.W. (2012). Nurses’ attitudes and experiences surrounding palliative sedation: Components for developing policy for nursing professionals. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15, 432–437. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0336

Regmi, K., Naidoo, J., & Pilkington, P. (2010). Understanding the processes of translation and transliteration in qualitative research.International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9, 16–25.

Rich, B. (2012). Terminal suffering and the ethics of palliative sedation. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 21, 30–39. doi:10.1017/S0963180111000478

Rietjens, J.A., Hauser, J., van der Heide, A., & Emanuel, L. (2007). Having a difficult time leaving: Experiences and attitudes of nurses with palliative sedation. Palliative Medicine, 21, 643–649. doi:10.1177/0269216307081186

Rosengarten, O.S., Lamed, Y., Zisling, T., Feigin, A., & Jacobs, J.M. (2009). Palliative sedation at home. Journal of Palliative Care, 25, 5–11.

Schildmann, E., & Schildmann, J. (2014). Palliative sedation therapy: A systematic literature review and critical appraisal of available guidance on indication and decision making. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17, 601–611. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0511

Shinjo, T., Morita, T., Hirai, K., Miyashita, M., Sato, K., Tsuneto, S., & Shima, Y. (2010). Care for imminently dying cancer patients: Family members’ experiences and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 142–148. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2793

Shirado, A., Morita, T., Akazawa, T., Miyashita, M., Sato, K., Tsuneto, S., & Shima, S. (2013). Both maintaining hope and preparing for death: Effects of physicians’ and nurses’ behaviors from bereaved family members’ perspectives. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 45, 848–858. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.014

Swart, S.J., van der Heide, A., van Zuylen, L., Perez, R.S., Zuurmond, W.W., van der Maas, P.J., . . . Rietjens, J.A. (2014). Continuous palliative sedation: Not only a response to physical suffering. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17, 27–36. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0121

van Deijck, R.H., Hasselaar, J.G., Verhagen, S.C., Vissers, K.C., & Koopmans, R.T. (2013). Determinants of the administration of continuous palliative sedation: A systematic review. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16, 1624–1632. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0173

van Dooren, S., van Veluw, H.T., van Zuylen, L., Rietjens, J.A., Passchier, J., & van der Rijt, C.C. (2009). Exploration of concerns of relatives during continuous palliative sedation of their family members with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 38, 452–459. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.11.011

World Health Organization. (2016). WHO definition of palliative care. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en

About the Author(s)

Tursunov is a palliative care nurse, and Cherny is the director of Cancer Pain and Palliative Medicine, both at the Shaare Zedek Medical Center; and Ganz is a professor in the School of Nursing at Hadassah Hebrew University, all in Jerusalem, Israel. No financial relationships to disclose. All of the authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, statistical support, analysis, and manuscript preparation. Tursunov and Cherny completed the data collection. Tursunov can be reached at olgatursunov@gmail.com, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted December 2015. Accepted for publication February 16, 2016.